eBook - ePub

Women, Science, and Technology

A Reader in Feminist Science Studies

- 606 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Women, Science, and Technology

A Reader in Feminist Science Studies

About this book

Women, Science, and Technology is an ideal reader for courses in feminist science studies. This third edition fully updates its predecessor with a new introduction and twenty-eight new readings that explore social constructions mediated by technologies, expand the scope of feminist technoscience studies, and move beyond the nature/culture paradigm.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Women, Science, and Technology by Mary Wyer,Mary Barbercheck,Donna Cookmeyer,Hatice Ozturk,Marta Wayne in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

SECTION I

From Margins to Center: Educating Women for Scientific Careers

CHAPTER 1

Science Faculty's Subtle Gender Biases Favor Male Students

A 2012 report from the President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology indicates that training scientists and engineers at current rates will result in a deficit of 1,000,000 workers to meet United States workforce demands over the next decade (1). To help close this formidable gap, the report calls for the increased training and retention of women, who are starkly under-represented within many fields of science, especially among the professoriate (2–4). Although the proportion of science degrees granted to women has increased (5), there is a persistent disparity between the number of women receiving PhDs and those hired as junior faculty (1–4). This gap suggests that the problem will not resolve itself solely by more generations of women moving through the academic pipeline but that instead, women's advancement within academic science may be actively impeded.

With evidence suggesting that biological sex differences in inherent aptitude for math and science are small or nonexistent (6–8), the efforts of many researchers and academic leaders to identify causes of the science gender disparity have focused instead on the life choices that may compete with women's pursuit of the most demanding positions. Some research suggests that these lifestyle choices (whether free or constrained) likely contribute to the gender imbalance (9–11), but because the majority of these studies are correlational, whether lifestyle factors are solely or primarily responsible remains unclear. Still, some researchers have argued that women's preference for nonscience disciplines and their tendency to take on a disproportionate amount of child- and family-care are the primary causes of the gender disparity in science (9–11), and that it “is not caused by discrimination in these domains” (10). This assertion has received substantial attention and generated significant debate among the scientific community, leading some to conclude that gender discrimination indeed does not exist nor contribute to the gender disparity within academic science (e.g., refs. 12 and 13). Despite this controversy, experimental research testing for the presence and magnitude of gender discrimination in the biological and physical sciences has yet to be conducted. Although acknowledging that various lifestyle choices likely contribute to the gender imbalance in science (9–11), the present research is unique in investigating whether faculty gender bias exists within academic biological and physical sciences, and whether it might exert an independent effect on the gender disparity as students progress through the pipeline to careers in science. Specifically, the present experiment examined whether, given an equally qualified male and female student, science faculty members would show preferential evaluation and treatment of the male student to work in their laboratory. Although the correlational and related laboratory studies discussed below suggest that such bias is likely (contrary to previous arguments) (9–11), we know of no previous experiments that have tested for faculty bias against female students within academic science.

If faculty express gender biases, we are not suggesting that these biases are intentional or stem from a conscious desire to impede the progress of women in science. Past studies indicate that people's behavior is shaped by implicit or unintended biases, stemming from repeated exposure to pervasive cultural stereotypes (14) that portray women as less competent but simultaneously emphasize their warmth and likeability compared with men (15). Despite significant decreases in overt sexism over the last few decades (particularly among highly educated people) (16), these subtle gender biases are often still held by even the most egalitarian individuals (17), and are exhibited by both men and women (18). Given this body of work, we expected that female faculty would be just as likely as male faculty to express an unintended bias against female undergraduate science students. The fact that these prevalent biases often remain undetected highlights the need for an experimental investigation to determine whether they may be present within academic science and, if so, raise awareness of their potential impact.

Whether these gender biases operate in academic sciences remains an open question. On the one hand, although considerable research demonstrates gender bias in a variety of other domains (19–23), science faculty members may not exhibit this bias because they have been rigorously trained to be objective. On the other hand, research demonstrates that people who value their objectivity and fairness are paradoxically particularly likely to fall prey to biases, in part because they are not on guard against subtle bias (24, 25). Thus, by investigating whether science faculty exhibit a bias that could contribute to the gender disparity within the fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (in which objectivity is emphasized), the current study addressed critical theoretical and practical gaps in that it provided an experimental test of faculty discrimination against female students within academic science.

A number of lines of research suggest that such discrimination is likely. Science is robustly male gender-typed (26, 27), resources are inequitably distributed among men and women in many academic science settings (28), some undergraduate women perceive unequal treatment of the genders within science fields (29), and nonexperimental evidence suggests that gender bias is present in other fields (19). Some experimental evidence suggests that even though evaluators report liking women more than men (15), they judge women as less competent than men even when they have identical backgrounds (20). However, these studies used undergraduate students as participants (rather than experienced faculty members), and focused on performance domains outside of academic science, such as completing perceptual tasks (21), writing nonscience articles (22), and being evaluated for a corporate managerial position (23).

Thus, whether aspiring women scientists encounter discrimination from faculty members remains unknown. The formative predoctoral years are a critical window, because students' experiences at this juncture shape both their beliefs about their own abilities and subsequent persistence in science (30, 31). Therefore, we selected this career stage as the focus of the present study because it represents an opportunity to address issues that manifest immediately and also resurface much later, potentially contributing to the persistent faculty gender disparity (32, 33).

CURRENT STUDY

In addition to determining whether faculty expressed a bias against female students, we also sought to identify the processes contributing to this bias. To do so, we investigated whether faculty members' perceptions of student competence would help to explain why they would be less likely to hire a female (relative to an identical male) student for a laboratory manager position. Additionally, we examined the role of faculty members' preexisting subtle bias against women. We reasoned that pervasive cultural messages regarding women's lack of competence in science could lead faculty members to hold gender-biased attitudes that might subtly affect their support for female (but not male) science students. These generalized, subtly biased attitudes toward women could impel faculty to judge equivalent students differently as a function of their gender.

The present study sought to test for differences in faculty perceptions and treatment of equally qualified men and women pursuing careers in science and, if such a bias were discovered, reveal its mechanisms and consequences within academic science. We focused on hiring for a laboratory manager position as the primary dependent variable of interest because it functions as a professional launching pad for subsequent opportunities. As secondary measures, which are related to hiring, we assessed: (i) perceived student competence; (ii) salary offers, which reflect the extent to which a student is valued for these competitive positions; and (iii) the extent to which the student was viewed as deserving of faculty mentoring.

Our hypotheses were that: Science faculty's perceptions and treatment of students would reveal a gender bias favoring male students in perceptions of competence and hireability, salary conferral, and willingness to mentor (hypothesis A); Faculty gender would not influence this gender bias (hypothesis B); Hiring discrimination against the female student would be mediated (i.e., explained) by faculty perceptions that a female student is less competent than an identical male student (hypothesis C); and Participants' preexisting subtle bias against women would moderate (i.e., impact) results, such that subtle bias against women would be negatively related to evaluations of the female student, but unrelated to evaluations of the male student (hypothesis D).

RESULTS

A broad, nationwide sample of biology, chemistry, and physics professors (n = 127) evaluated the application materials of an undergraduate science student who had ostensibly applied for a science laboratory manager position. All participants received the same materials, which were randomly assigned either the name of a male (n = 63) or a female (n = 64) student; student gender was thus the only variable that differed between conditions. Using previously validated scales, participants rated the student's competence and hireability, as well as the amount of salary and amount of mentoring they would offer the student. Faculty participants believed that their feedback would be shared with the student they had rated (see Materials and Methods for details).

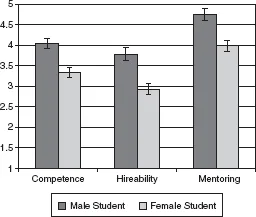

Student Gender Differences

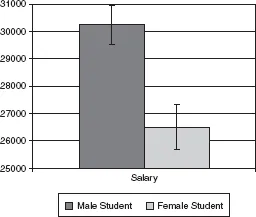

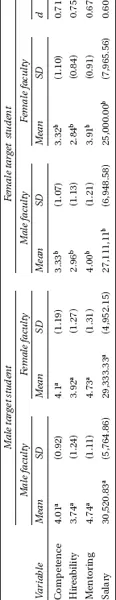

The competence, hireability, salary conferral, and mentoring scales were each submitted to a two (student gender; male, female) × two (faculty gender; male, female) between-subjects ANOVA. In each case, the effect of student gender was significant (all P > 0.01), whereas the effect of faculty participant gender and their interaction was not (all P > 0.19). Tests of simple effects (all d > 0.60) indicated that faculty participants viewed the female student as less competent [t(125) = 3.89, P > 0.001] and less hireable [t (125) = 4.22, P > 0.001] than the identical male student (Figure 1.1 and Table 1.1). Faculty participants also offered less career mentoring to the female student than to the male student [t (125) = 3.77, P > 0.001]. The mean starting salary offered the female student, $26,507.94, was significantly lower than that of $30,238.10 to the male student [t (124) = 3.42, P > 0.01] (Figure 1.2). These results support hypothesis A.

In support of hypothesis B, faculty gender did not affect bias (Table 1.1). Tests of simple effects (all d > 0.33) indicated that female faculty participants did not rate the female student as more competent [t (62) = 0.06,

Figure 1.1 Competence, hireability, and mentoring by student gender condition (collapsed across faculty gender). All student gender differences are significant (P > 0.001). Scales range from 1 to 7, with higher numbers reflecting a greater extent of each variable. Error bars represent SEs. nmale student condition = 63, nfemale student condition = 64.

P = 0.95] or hireable [t (62) = 0.41, P = 0.69] than did male faculty. Female faculty also did not offer more mentoring [t (62) = 0.29, P = 0.77] or a higher salary [t (61) = 1.14, P = 0.26] to the female student than did their male colleagues. In addition, faculty participants' scientific field, age, and tenure status had no effect (all P > 0.53). Thus, the bias appears pervasive among faculty and is not limited to a certain demographic subgroup.

Mediation and Moderation Analyses

Thus far, we have considered the results for competence, hireability, salary conferral, and mentoring separately to demonstrate the converging results across these individual measures. However, composite indices of measures that converge on an underlying construct are more statistically reliable, stable, and resistant to error than are each

Figure 1.2 Salary conferral by student gender condition (collapsed across faculty gender). The student gender difference is significant (P > 0.01). The scale ranges from $15,000 to $50,000. Error bars represent SEs. n male student condition = 63, n female student condition = 64.

Table 1.1 Means for student competence, hireability, mentoring and salary conferral by student gender condition and faculty gender

Scales for competence, hireability, and mentoring range from 1 to 7, with higher numbers reflecting a greater extent of each variable. The scale for sal...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Feminism, Science and Technology—Why It Still Matters

- Section 1. From Margins to Center: Educating Women for Scientific Careers

- Section 2. Feminist Approaches In/To Science and Technology

- Section 3. Technologies of Sex, Gender, and Difference

- Section 4. Thinking Theoretically

- Section 5. Theoretical Horizons in Feminist Technoscience Studies

- Contributors

- Credits

- Index