- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Jurgen Habermas

About this book

First Published in 2004. Pusey's lucid introduction to Habermas enables students to get to grips with all aspects of Habermas's rewarding but sometimes difficult work.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Jurgen Habermas by Michael Pusey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Scienze sociali & Sociologia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Foundations

FROM THE PHILOSOPHICAL FOUNDATIONS…

Jürgen Habermas’s first major work is aptly titled Knowledge and Human Interests [1] (KHI). It is here that Habermas establishes the philosophical foundations for the stream of social-theoretical and sociological studies that have followed in the twenty years since the design of KHI was first announced in Habermas’s inaugural lecture at Frankfurt in June of 1965. Although Habermas has had second thoughts about some aspects of KHI he still holds fast to its central convictions. It is still the best point of entry to his work.

At the very beginning of KHI, Habermas invites us to ‘reconstruct’ all the most essential philosophical discussions of our modern period as ‘a judicial hearing’ aimed at deciding the single question of ‘how is reliable knowledge possible?’. And so the book is announced for what it is, namely, a comprehensive study of epistemology which, as Habermas tells us, was conceived as a ‘systematic history of ideas with a practical intention’—a very unfamiliar notion indeed for anyone outside the German tradition.

Yet the unusual image of a ‘judicial hearing’ is a sure pointer to the heart of the whole project and to its philosophical ancestry. Immanuel Kant, the father of the German Enlightenment, and of the intellectual tradition which Habermas inherits, introduces the Critique of Pure Reason with the following image [2]:

Reason…must approach nature in order to be taught by it: but not in the character of a pupil who agrees to everything the master likes, but as an appointed judge who compels the witnesses to answer questions he himself proposes.

How is reliable knowledge possible? Although the detail and method of Habermas’s arguments are both difficult and foreign for the British reader the answer is, in a general way, very clear, and very Kantian in character. Reliable knowledge is only possible when science assumes its proper, subordinate place as one of the accomplishments of reason [3]. KHI is a history of ideas with a ‘practical intention’ inasmuch as its aim, its practical intention, is to rescue the rationalist heritage and to retrace the steps which reason has taken to its prison in the cellars of modern science.

Habermas is more than willing to honour the achievements of science. He is for science and (like Kant 200 years before him) he will defend it against dogmatic metaphysics and, in our own time, against the romantic views of Nature and against the attacks of conservatives who want to oppose it with blind traditions. His purpose is to insist that science should be done better, in a more philosophically knowing way, and so with tougher epistemological standards! The focus of his criticisms—of modernity, and of the modern epistemology that rules over just about every branch of modern learning from natural science to the humanities—is the relationship between science and philosophy. Knowledge and Human Interests is a critique of modern positivism. It seeks to show how positivism has mutilated our reason and swallowed it whole into a limited theory and practice of science. The ‘practical intent’ of this history of ideas is to trace the gradual establishment of positivism and thus exhume the larger concept of reason that it has sought to bury. It is therefore not an attack on science but an attack rather upon an arrogant and mistaken self-understanding of science that reduces all knowledge to a belief in itself. He calls this ‘scientism’ and it means [4],

science’s belief in itself: that is, the conviction that we can no longer understand science as one form of possible knowledge, but rather must identify knowledge with science.

Scientism is also the ‘basic orientation prevailing in analytic philosophy, until recently the most…influential philosophy of our time’. The claim which he seeks to vindicate in three hundred pages of brilliant but difficult argument is that [5]

science can only be comprehended epistemologically, which means as one category of possible knowledge, as long as knowledge is not equated with…scientistic self-understanding of the actual business of [scientific] research.

He wants to rescue the more ‘comprehensive rationality of reason that has not yet shrunk to a set of methodological principles’. Accordingly, the task of KHI is to outline, and to justify, a more comprehensive epistemology (with tougher standards) that can rehabilitate the claims of reason in human affairs. In terms of the Kantian metaphor he must restore the authority of the ‘judge’. This he does by means of ‘critical reconstructions’ first of Kant and then of Hegel, Comte and Mach, Pierce, Dilthey, Freud and Nietzsche among others. All these criticisms are aimed at identifying the errors which would cumulatively lead to the bankruptcy of reason in modern philosophy and science. Our problem is that these discussions mostly presuppose an intimate knowledge of the classical figures whom Habermas addresses almost as partners in a dialogue. Yet, as we shall see, the basic outlines of the epistemology that Habermas hopes to vindicate can be summarized without too much difficulty.

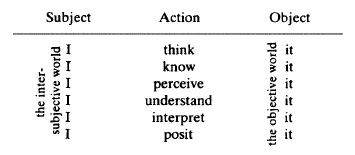

This will be easier if we have in mind the following elementary schema.

At the centre of the schema are some transitive verbs referring to knowledge and belief. The first, obvious but nonetheless basic, point is, of course, that every act of knowing, perceiving, etc. is a human action that must, accordingly, have a subject and an object. Even with these elementary terms we can begin to grasp the common motif of Habermas’s careful arguments against the ‘objectivistic illusion of unreflecting science’, that is, of modern positivism. Every undergraduate with a unit of behavioural psychology in his or her academic record will have had some experience of the most vulgar example of what Habermas means. In this, as in every other field of positivistic science, we are asked to approach the object world as a disaggregated jumble of discrete objects of perception, as a jumble of ‘its’. We are set the task of uncovering the regularities in the behaviour of these atoms of substance by means of an experimental method. The criterion of success lies in the predictive power of the uncovered ‘laws’ that must produce replicable results. This means results that are independent of the author, the inventor, in short of the thinking subject who in the first place conceived the problem, the method and the experiment and who thereby created the knowledge. One half of the underlying assumption is that knowledge is always reducible to the totality of discovered properties of the object world. The other half is that the subject—the actor, the creator, the knower, the inventor, the scientist—is at worst a pollutant in his own purely objective world, or at best, a ghost in the machine of science and something that must be methodologically controlled and, so far as is possible, eliminated. In a nutshell these are the assumptions of a positivist science that occasioned such hot debate over the nature and theory of science in the 1970s. They still underlie public perceptions of science and the mundane practice of science in every field at the botton of the pyramid of modern science. Habermas joined those debates [6] with the aim of challenging, at the apex of the pyramid, the source of these epistemological assumptions in the orthodox empiricism that still dominates most theories of science.

Let us return for a moment to this simple image of subject-knower— object. Habermas has three aims:

- The first is to explain, in a similar way to Kant 200 years before him, that knowledge is necessarily defined both by the objects of experience and by a priori categories and concepts that the knowing subject brings to every act of thought and perception. Even ‘space’ and ‘time’, the basic notions of such rigorous sciences as physics, are not supplied by experience alone. Indeed, as Kant argued in the Critique of Pure Reason, they make no sense without concepts, ideas, that are given a priori, independently of all experience. Ideas and concepts are not simply, as classical empiricism since Hume would have it, merely ‘weak sense impressions’. They are not derivations of experience but constituents of it: the essential constituents of logic are not copied or taken from the object world; instead they are given in the categories and forms that the subject brings to the act of perception. The validity of scientific knowledge, of hermeneutic understanding, and of mundane knowledge always depends as much on its ‘subjective’, and intersubjective, constituents as it does on any methodologically verifiable observation and experience of the object-world. So, we can see that Habermas’s aim is to ‘put reason and rationality back into the knowing subject’. It would be entirely misleading to cast Habermas as a neo-classical idealist [7]—although this is just what some of his critics, orthodox marxists [8] and others, have tried to do. Habermas explicitly rejects the idealist epistemology of innate ideas! However, it is clear that his whole work hangs on the solidity of an epistemology in which the validation of knowledge and understanding is returned to the knowing and reasoning subject.

- His second aim is to show that the knowing subject is also social and, as we shall see later, dynamic as well. Here there is a sharp break with Kant and with the classical philosophical tradition in which epistemological questions are treated as the concern of a solitary individual confronted with the puzzle of the universe. The modernization of the Kantian legacy requires, with Hegel and Marx, a full recognition of the fact that knowledge and understanding are socially coordinated and at every moment conditioned and mediated by our historical experience. Kant’s philosophical arguments are cast, as were those of classical Greek philosophy, into a timeless world outside history and, to some extent, beyond social experience as well. One of the aims of KHI is to secure the foundations of sociology and to show that there is no knower without culture, and that all knowledge is mediated by social experience. The knower is, of course, not surrendered to the empiricist prejudice that the subject is, once more, a mere reflex of the object world, or that ideas are, again, just weak sense impressions, the imprints of the object world that form it only ‘from the outside in’. On the contrary, the subject still brings its own categories and ‘faculties of reason’ to the constitution of the object and thus to the formative moment of knowledge. As we shall see later the distinctive feature of Habermas’s work is that processes of knowing and understanding are grounded, not in philosophically dubious notions of a transcendental ego, but rather in the patterns of ordinary language usage that we share in everyday communicative interaction.

- The third aim is to establish the validity of reflection. Every theory of knowledge must deal with the problem—potentially an infinitely regressive problem—of how it is that we find the knowledge with which to correct the knowledge that is now in doubt, and so on ad infinitum. Habermas’s aim is to show that the power of reason is grounded in the process of reflection, and from this perspective, to counter the usual claim of traditional (British) empiricism that reflection conceived in this German way is just illusory introspection and, of course, that the only remedy for such defective knowledge is to be found in an ever more exact understanding of external Nature [9].

Habermas has no wish to protect bad science and he certainly wants imperfect knowledge to be corrected with better scientific observation where that is appropriate. His larger argument is that the defects of imperfect knowledge—and this is simply another term for irrationality—originate in the ‘cognitive attitude’ of scientistic (positivist) science. Empiricism is a fundamentally misconceived attitude that has warped the logic of science in such a way that the scientific community cannot [10],

perceive itself as the subject of reflection. By their scientific orientation, its members are obliged to objectivate themselves. Unable to meet the demand for self-reflection without simultaneous abandonment of their theory, they reject that demand by conceiving a programme of science theory which would make all demands of self-reflection immaterial.In other words, the terms that we bring from within ourselves to the process of enquiry—in any and every domain, including science—are amenable to a reflection that is rational for the very reason that it carries the potential for a more inclusive conceptualization that is better attuned to the common interest of the human condition.

These three aims are worked out in Habermas’s ‘theory of knowledge-constitutive interests’ that he first stated in the inaugural Frankfurt lecture in 1965 [11]. The theory systematically explains the threefold structure of his epistemology. It is central to all his work and rather easier to grasp than the daunting jargon might otherwise suggest.

Some of the essential elements have already been suggested. In thought and action we simultaneously both create and discover the world; and knowledge crystallizes in this generative relation of the subject to the world. Every ‘speaking and acting subject’ constitutes knowledge, however idiosyncratically and variably, in the light of three universally given ‘knowledge-constitutive interests’, or ‘cognitive interests’, that are given a priori in our relation to the world [12] (see Table 1).

Table 1

In the case of the natural or ‘empirical-analytic’ sciences (Naturwissenschaften), it is our universal interest in the technical control of nature that constitutes ‘the meaning of possible statements and establishes rules both for the construction of theories and for their critical testing’ [13]. This is, as we have seen, the basis of Habermas’s critical rejection of classical empiricism. There is no defensible basis for an ontology of an independently existing world of things ‘out there’ that constitute knowledge objectivistically, ‘from the outside in’ and according to a correspondence theory of truth—a mistaken assumption that each atom of knowledge must correspond with an atom of independently existing substance. This is not a denial of objective reality. The point is rather that what we know about nature is always defined by the cognitive attitude which informs our scientific enquiry. Habermas insists that, in this domain, our attitude is fundamentally instrumental. Nature is conceived, even in the theoretical and ‘pure’ sciences, in terms of our interest in controlling it. That, at any rate, is the telos, the implicit objective, of all scientific enquiry.

As a species we have a second universal interest, namely in mutual understanding in the everyday conduct of life. To understand what this means we must again overcome the prejudices of parts of the liberal British philosophical tradition in which other individual human beings are set on a par with objects in nature and apprehended with the same objectivist epistemology by a supposedly self-sufficient individual knower. Habermas insists that the ‘objectivity of experience consists precisely in its being intersubjectively shared’ [14]. In everyday social interaction, as in all studies of society, literature, art and history, our understanding presupposes a ‘preunderstanding’ [15] of the other speaking and acting subjects whose meanings we seek to interpret. The proof of this is that socialization is a universal precondition for individual identity: the specific contents of my subjective world may be very different to those of your inner world but, like it or not, I can have no coherent identity unless I can enter your experience in a way that allows me to understand what you mean. The same is true for you and so we share with all other human beings, in every place and time, a universal interest in the mutual self-understanding that underpins all social action. Habermas calls this the ‘practical’ interest that constitutes knowledge in the ‘historical-hermeneutic’ sciences—the clumsy term that, in the absence of a notion of ‘Geist’ (collective mind? spirit? consciousness?), a term we must use to translate ‘Geisteswissenschaften’, a term that is so naturally paired in the German tradit...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Editor’s foreword

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1: Foundations

- 2: Culture, evolution, rationalization and method

- 3: Communication and social action

- 4: The political sociology of advanced capitalist Societies

- Concluding comments

- Further reading