- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Menstrual Disorders

About this book

What does modern medical science know about menstruation? Less than is commonly assumed, according to Annette and Graham Scambler. In this thought-provoking book, they challenge orthodox thinking on menstruation and disorders associated with it. Based on women's own experience and accounts of menstruation and menstrual disorders, their study will prompt health workers to rethink their approaches to menstrual phenomena. It shows how women are conditioned to regard menstruation as problematic, highlights the disadvantages as well as the advantages of progressive medicalization of menstrual phenomena, and discuss how menstruation is perceived within male culture.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Medical concepts of menstrual disorders

The thesis that the medical perspective on menstruation and menstrual disorders is both limited and limiting will inform much of the analysis offered in this volume. It will be argued, for example, that medicine relies on applications of the concepts of normality and abnormality which are highly contentious and contestible. This first chapter, however, documents and describes rather than analyses the medical perspective. The aim is to outline the medical approach to menarche and the menstrual cycle in general, and to disorders associated with the menstruum in particular. Special attention is paid to the so-called ‘premenstrual syndrome’, which remains controversial within medicine as well as outside it.

MENARCHE AND THE MENSTRUAL CYCLE

The menarche is defined as the age at which the first menstrual bleed occurs. Over the past century and a half the average age of menarche has declined in modern western countries from 17 years to 13 years, the normal range now being 10 to 16 years. This decline can almost certainly be attributed to a combination of a rise in material living standards and improved and more accessible health care, since body weight at menarche seems to have remained constant throughout this period, at 45–7 kg. It has been suggested that a critical weight may need to be attained for menarche to occur (Elder 1988:30).

The menarche occurs fairly late in puberty, which begins with a growth spurt; this is followed by the development of the secondary sex characteristics, including breast development, a widening of the hips, pubic hair, and the development of external genitalia. What the menarche indicates when it does occur is that there is sufficient activity within the ovary to have secreted some oestrogen to induce uterine development and to have caused bleeding. It does not signify fertility since, during the first two years or so, the cycles are primarily anovulatory (i.e. no ovum is discharged).

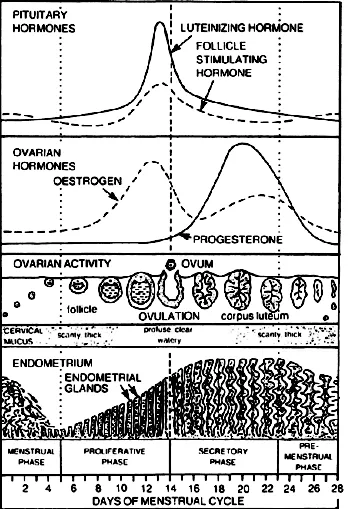

The events of the menstrual cycle are not yet well understood either in puberty or in adulthood, although there is a broad uniformity to textbook accounts which we shall follow here. The menstrual cycle in adulthood takes an average of 28 days and involves the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland, the ovaries, the endometrium and the secondary sex organs. The periodicity is inherent in the hypothalamus, which controls the cycle. The hypothalamus produces hormones, or ‘chemical messengers’, which act on the pituitary gland. This stimulation of the pituitary gland leads to the production of two gonadotrophic hormones: follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). FSH brings about the development of Graafian follicles within the ovary, each follicle consisting of an ovum and surrounding cells. Approximately fifty of these follicles start to mature, but normally only one dominant follicle matures fully while the remainder retrogress. This dominant follicle enlarges under the influence of FSH and, as a result of a sudden surge of LH, ruptures and releases an ovum. Ovulation usually occurs around day 14 of the cycle.

As the dominant follicle matures and enlarges the cells surrounding the ovum produce the hormone oestrogen; and when ovulation occurs and the follicle collapses, becoming a corpus luteum or ‘yellow body’, the hormone progesterone is produced. These two hormones, oestrogen and progesterone, importantly affect the endometrium or lining of the womb. Oestrogen first produces thickening or proliferation of the endometrium, then progesterone produces secretions to fill the glands of the endometrium in preparation for implantation of the ovum if fertilization takes place. If fertilization does not take place, then the corpus luteum degenerates into a hyaline body known as the corpus albicans. The levels of oestrogen and progesterone fall and the endometrium is shed, appearing as blood—the process we know as menstruation. Menstruation has been described as ‘the outward sign of the end of an abortive cycle and the optimistic commencement of the next’ (but see chapter 2). This much-simplified account of the cycle is represented diagrammatically in Figure 1.1.

It would be misleading to leave this account of a ‘normal’ cycle without some comment on variation between women. Such variation has important implications, both for medical notions of disease associated with the menstruum and for women’s ideas about menstrual illness. These implications will be discussed in detail in chapters 2 and 3. Here we shall merely note the extent of known variation, in relation first to menstrual blood loss, and second, to length of menstrual cycle.

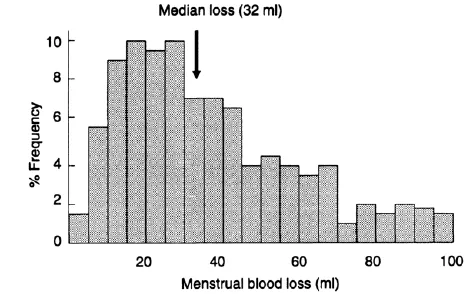

A study of several hundred women in Oxford has shown that, on average, women lose 33 ml. in menstrual blood, with 90 per cent losing less than 80 ml. and only 1 per cent 200 ml. or more; but there is considerable variation (See Figure 1.2). It is worth recording that more than 90 per cent of blood loss seems to occur within the first three days of menstruation, regardless of either the total loss or the total number of days of bleeding (average 4 or 5 days) (Anderson and McPherson 1983).

Figure 1.1 Schematic description of menstruation and ovulation

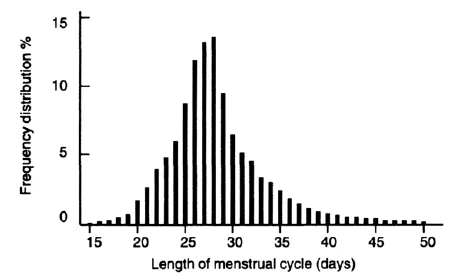

Consider also variation in cycle length. It was discovered many hundreds of years ago that the length of the menstrual cycle approximated to the phases of the moon, beginning again every 28 days. Over the succeeding centuries the 28- day menstrual cycle has become a kind of symbol of health and normality in relation to reproductive function. Variation from the 28-day ‘norm’ has been and still is seen as problematic, or potentially so, by physicians and women alike. But one recent study of several hundred women from menarche to menopause has shown that, although the 28-day cycle is—just—the most common cycle length, it characterizes only 1:8 cycles (Vollman 1977). As Figure 1.3 shows, variation of cycle length is marked. This is particularly so in relation to age. Mean menstrual cycle length decreases from 35 days at age 12 to a minimum of 27 days at age 43, and increases to 52 days at age 55. Clearly the ‘normality’ of the 28-day cycle has to be qualified.

Figure 1.2 Variations in menstrual blood loss. Frequency distribution (%) of menstrual blood loss in several hundred women in Oxford before insertion of an intrauterine device.

Source: Unpublished data from J. Guillebaud, reported in Anderson and McPherson 1983

TYPES OF MENSTRUAL DISORDER

In the biomedical language of one recent textbook, ‘menstruation depends upon an intact hypothalamic-pituitary axis, normal ovarian function, a functionally responsive uterus and an intact outflow tract, i.e. cervix and vagina. A disturbance of any one of these components may result in disordered menstrual function’ (Elder 1988:34). Three main types of disorder or, more precisely, symptoms of disorder, are commonly identified: amenorrhoea or absence of menstruation, menorrhagia or excessive menstruation, and dysmenorrhoea or painful menstruation. The author of the textbook cited is not alone in adding a fourth ‘symptom group’, premenstrual syndrome, but this raises special issues and will here be examined separately.

Figure 1.3 Variations in length of menstrual cycle. Frequency distribution (%) of length of menstrual cycle in days, from menarche to menopause; 31,645 menstrual cycle lengths, recorded by 656 women aged 11 to 58 years.

Source: Vollman 1977

Amenorrhoea

Amenorrhoea may be apparent, primary or secondary. Apparent amenorrhoea, more appropriately termed cryptomenorrhoea, refers to a situation in which menstruation is occurring but the loss fails to escape from the vagina because of an obstruction, most often an ‘imperforate hymen’. Primary amenorrhoea refers to a situation in which menstruation has not commenced by the age of 16 or 17; after this age it is considered less likely that it will start spontaneously. Secondary amenorrhoea refers to a situation in which menstruation ceases after it has been established for a period of months or years.

Not all physicians accept the distinction between primary and secondary amenorrhoea as useful, however. According to one text directed at general practice, for example, ‘there is so much overlap in causes of primary and secondary amenorrhoea that it is not helpful to consider them as separate entities in relation to diagnosis. Instead, the differential diagnosis of amenorrhoea can be based on the main pathologies that give rise to the problem…. Congenital disorders usually present as primary amenorrhoea but almost all causes of secondary amenorrhoea can present as primary if they present before the age of 16 years’ (Anderson and McPherson 1983:32).

Primary amenorrhoea may be due to a variety of causes, frequently interrelated, although the mechanisms are not yet well understood. In a number of girls it derives from some genetic abnormality (e.g. failure of the uterus, vagina or ovaries to develop). In others it is a consequence of pituitary or thyroid disorders. It was noted earlier that a critical weight has to be reached before menarche can occur. Thus primary amenorrhoea can be caused by an overly rigorous diet, or by weight loss, as in anorexia nervosa; it may also be caused by obesity, although ‘the degree of obesity that delays menarche is far greater than the degree of leanness that blocks the menstrual cycle’ (Weideger 1975:90). But it may also follow some traumatic episode or life event. It is often seen, for example, in women who have just left home, like student nurses (see chapter 6).

It is worth recording that the most common cause of secondary amenorrhoea is pregnancy, a possibility sometimes overlooked by women themselves. Another physiological cause is premature menopause, which can be as early as 35. Some women develop secondary amenorrhoea after stopping oral contraceptives. For others it may be associated with general disease such as pulmonary tuberculosis or severe anaemia. But, as Anderson and McPherson claim, there is a considerable overlap in the causes of primary and secondary amenorrhoea, and most of the factors discussed in the previous paragraph— from glandular disorders to weight change to life events—are equally pertinent to a consideration of the aetiology of secondary amenorrhoea.

Reference might briefly be made here to oligomenorrhoea, which denotes long intervals between menstruation, which may occur only two or three times a year. The term implies bleeding following ovulation. It frequently heralds either the onset of secondary amenorrhoea or premature menopause.

In a girl suffering from primary amenorrhoea who has a normal uterus and vagina, and is chromatin positive, the diagnosis is likely to be delayed menarche. Nowadays physicians generally advise waiting, since menstruation is not established in some individuals until the age of 19 or 20, and hormones given to induce bleeding may inhibit ovulation. But if a definite cause for amenorrhoea is discovered, then the treatment is that of the cause. Since, as we have indicated, both primary and secondary amenorrhoea can have multiple causes, it will not be possible to summarize all forms of treatment here. Rather, discrete causes and treatments will be dealt with in the main body of the book as and when the need arises.

Menorrhagia

Menorrhagia refers to excessive uterine bleeding with regular menstruation. It can be distinguished from metrorrhagia, which means irregular or continuous bleeding from the uterus; polymenorrhoea, which refers to frequent and often profuse menstruation; and epimenorrhoea, or intermenstrual bleeding, which means uterine bleeding apart from normal menstruation (Barnes and Chamberlain 1988). Menorrhagia is difficult to assess, given the extent of variation of blood loss in the female population; and, like amenorrhoea, it can have a number of different causes.

Uterine fibroids are the commonest cause; they rarely disturb cycle length, so menstruation is regular. Other lesions of the body of the uterus, or of the cervix or ovary, can present as menorrhagia. Complications of pregnancy (e.g. abortion or ectopic pregnancy) can lead to menorrhagia, as can the presence of ‘foreign bodies’, such as intrauterine contraceptives, in the uterus. Certain blood disorders can cause menorrhagia. Thyroid dysfunction (i.e. hyper- or hypothyroidism) is another known cause. And there can also be psychosomatic causes, for example life events involving severe emotional shock.

In as many as half the cases of menorrhagia no cause can be found, leading physicians to refer to ‘dysfunctional uterine bleeding’, or, as Anderson and McPherson prefer, ‘unexplained menorrhagia’ (1983:21). This seems to be particularly common soon after the menarche, before the establishment of a regular cycle, and close to the menopause.

A wide range of hormonal and non-hormonal drugs are used to reduce menstrual blood loss in women with dysfunctional uterine bleeding. If a discrete cause of menorrhagia is discovered, then the treatment is that of the cause. We shall confine ourselves here to a brief consideration of the treatment of the commonest cause, uterine fibroids. It has been estimated that one in five women develop uterine fibroids, although these are generally symptomless and undiagnosed. They rarely become malignant. They usually only cause problems in pre-menopausal women, since they seem to undergo atrophy after the menopause. They can be single or multiple and vary enormously in size. Treatment depends partly on size, partly on the degree of menstrual distress, and partly on the proximity of the menopause. If the menopause is near treatment tends to be conservative, in anticipation that the fibroids will atrophy when menstruation ceases. Conservative drug therapy is also used in younger women if the fibroids are not too large. But if the uterus is considerably enlarged, or there is associated pain, then surgery may be required: myomectomy if the woman wishes to preserve her fertility, or hysterectomy if not.

Mention should also be made here of the diagnostic and therapeutic role of uterine curettage (D and C) in women with menorrhagia. Traditionally, D and Cs have been much favoured by gynaecologists. However, their value as therapeutic interventions has been called into question of late. Measurement of menstrual blood loss suggests there is no long-term benefit for women with menorrhagia. There is uncertainty also about its diagnostic role, especially in women under 35. Its main value would seem to be as a screening procedure for endometrial cancer, which is rare in younger women. Vessey and his colleagues (1979) have calculated that, taking all women under 35 in Scotland, only two endometrial cancers would be expected to be present in one year, and three to four thousand D and Cs would have to be done at the current rate to identify the two cases. Not surprisingly perhaps, increasing use is being made of alternative out-patient techniques for sampling the endometrium.

Nor would the D and C seem to be a very effective screening device for older women. Analysis of over a thousand D and Cs in Oxford in 1973 showed that all endometrial carcinomas diagnosed at curettage had presented clinically with post-menopausal bleeding (MacKenzie and Bibby 1978). Since endometrial cancer rises markedly in older women, however, curettage may still be needed to exclude malignancy in women with menorrhagia who are over 40 (Anderson and McPherson, 1983).

Dysmenorrhoea

The word ‘dysmenorrhoea’, deriving from the Greek word meaning ‘difficult monthly flow’, refers to painful menstruation. It occurs in three main forms: primary (sometimes termed ‘spasmodic’ or ‘intrinsic’) dysmenorrhoea; secondary (sometimes termed ‘congestive’ or ‘acquired’) dysmenorrhoea; and membranous dysmenorrhoea. Primary dysmenorrhoea is a common complaint. Barnes and Chamberlain write,

Most normal women experience discomfort at the onset of menstruation, but in dysmenorrhoea pain is severe during the first hours or days of the periods; it may be continuous or spasmodic, like colic; it is often accompanied by vomiting, fainting, headaches and malaise. Pain is felt in the pelvis and lower back and may radiate to the legs. It does not begin at the onset of menstruation when the cycles are often anovular, and it is commonest in single women or infertile married women. It tends to lessen after 25 and to disappear after 30.

(1988:109)

Secondary dysmenorrhoea is rare before 25 and uncommon before 30. Pain usually starts three or four days before menstruation and may either be relieved or get worse when bleeding commences. It is felt in the pelvis and back and is made worse by exertion. Symptoms such as menorrhagia, sterility and dyspareunia may also be present.

The aetiology of primary dysmenorrhoea remains uncertain. There is rarely any pathological cause. One possibility is that the pain may be caused by ischaemia resulting from the powerful contractions of the uterine muscle that occur during the first days of menstruation. Secondary dysmenorrhoea does not occur without a pathological cause. The most common causes are pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis, fibroids and the presence of an intrauterine contraceptive device.

Treatment of primary dysmenorrhoea ranges from advice about menstrual hygiene and the use of simple analgesics to prescriptions (usually the pill) to inhibit ovulation and thus cause painless bleeding. The treatment of secondary dysmenorrhoea is aimed at the underlying cause; specific treatments will be discussed later in the text, when pertinent.

Membranous dysmenorrhoea is rare: severe pain is associated with ‘the passage of all the endometrium shed at menstruation in a single “cast” ’ (Barnes and Chamberlain 1988:111). It may occur at every cycle or only occasionally. Once the cast is passed the pain is relieved and menstruation continues normally. Treatment is difficult. Oestrogen therapy and D and C may help, and in intractable cases in older women hysterectomy may be performed.

Premenstrual syndrome

T...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Tables and Figures

- Editors’ Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1: Medical Concepts of Menstrual Disorders

- Chapter 2: A Sociological Perspective

- Chapter 3: Interpreting Women’s Perceptions of Menstruation

- Chapter 4: Women and Help-Seeking

- Chapter 5: Menstrual Change and Relationships with Men

- Chapter 6: Menstrual Change and Social and Work Activity

- Chapter 7: Rethinking Menstruation

- References

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Menstrual Disorders by Graham Scambler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Health Care Delivery. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.