1

THE ORGANISATION OF THE SCHOOL: CREATING A POSITIVE ETHOS

This chapter looks at:

- organisation of the school;

- ways of organising the whole school; organisational structures;

- leadership and positive ethos;

- leadership styles;

- communication.

It considers the importance of school organisation and the ways in which school leaders can organise schools effectively.

INTRODUCTION

It may sound simplistic, but effective schools are vibrant, enthusiastic and ever-changing organisations which don’t just suddenly happen; they actually have to be organised. In saying this, it is important that they are organised in such a way that there is a positive ethos and a learning atmosphere where every child succeeds in some way and where every adult works towards helping every child achieve his or her maximum potential. One common assumption about the purpose of schools that we must make is that they should develop the intellectual, social, emotional and physical abilities of all children. This is summarised in Table 1.1. The organisation of the school and how it works effectively will be geared to making sure that these purposes are central to how the school functions.

Table 1.1 The purpose of schools Intellectual purposes—making sure that children of all abilities are learning and that the organisation of the school supports this learning

ORGANISATION OF THE SCHOOL

The successful organisation of the school is really about managing all the diverse attitudes of the people that are involved in the process of running it day by day and year by year into something coherent and shared. This does not mean creating a situation in which everyone holds the same views or in which there is no disagreement about the nature of how to manage the organisation, although there is little doubt that, in effective schools, staff share an ability to work together towards a set of clearly understood purposes which are seen as reasonable to all those involved.

Managing the organisation of the school in all its complexities and subtleties is unlikely to be carried out effectively by those headteachers and leaders who stick rigidly to a top-down style of management. Success is much more likely to be achieved by using a variety of strategies that involve responding to the different needs of everyone involved.

There are several basic organisational concepts that are, in many ways, the backbone of the whole structure of a school and which need to be referred back to as the building blocks of how the school operates effectively and successfully. Here is a brief résumé of six key concepts.

1.

Objectives and aims

It is important to establish an aims statement that drives the school forward and is at the centre of everything that happens in the school. This should be a public statement that everyone is aware of and it should have been developed by all those with a vested interest in the school, including teachers, teaching assistants, parents, governors and, where appropriate, older children. At its core is a statement about what the school is trying to achieve.

There are many statements of intent in a primary school. Many of these relate to the curriculum, teaching, behaviour, anti-bullying, etc, and exist in policies relating to all kinds of subjects as well as in the school prospectus which is a key document for parents. But, all of these must always relate back to the core statement of intent which, as an aims statement, is the heart of what the school actually does. Table 1.2 is an example of a broad aims statement.

Table 1.2 School aims statement

2.

The structure of the school

This is about roles and responsibilities, tasks, areas of work and, in short, who does what, when and how. It is about communicating information, organising tasks, taking decisions and organising who works with whom. Primary schools are full of structures, including class groupings, teams, Key Stage planning teams, coordinators, senior teachers, timetables, etc. Some of these structures are determined externally, such as salary scales and admission policies for LEA schools, and others are decided internally, such as the allocation of posts above the main teachers’ pay spine, including management and leadership posts.

3.

Leadership

This is about who gets things going, who has responsibility and who offers direction to the school. It will be discussed in more detail later in the chapter. Usually in primary schools leadership is represented by the headteacher and the deputy headteacher. This has changed radically during the past few years and there are now important management roles allocated to all curriculum coordinators. In the teachers’ pay structure there are leadership posts which widen the senior teacher team to include such appointments as assistant headteachers. In fact, in effective schools most adults who work in them, including secretaries, site managers and chairs of governors, have to act as leaders on certain occasions.

4.

Power

This is not quite the same as leadership but it is about who has the authority to do things and who is able to use their power positively and who uses it negatively. Power often underpins the role of many leaders. Authority, which on most occasions is legitimate power, might stem from an individual coordinator’s expertise in music or technology, for example, or because of age and/or experience. Power can be seen as quite widely distributed, but it has to be said that the principal source of power in the primary school lies in the hands of the headteacher.

5.

Ethos

Each school has its own ethos which is determined by its underlying beliefs and values. The ethos or culture of a primary school is usually an amalgamation of social, moral and academic values. These values determine how children relate to each other, how staff and children relate and define relationships in terms of courtesy, care consideration, competition, individuality and mutual dependence, for example. The ethos is also about what is considered right and proper, for example helpfulness, cooperation, respect for others, and what are the beliefs upon which such things as the academic curriculum is based.

6.

Environmental relationships

Schools exist in an environment with which they constantly react. They are affected by their context which relates to the school type, its catchment area, the LEA, types of governors and the demands of central government and national policy.

In the rest of this chapter the brief descriptions of the ‘building blocks’ of school organisation outlined above are used as the basis for a closer investigation of what constitutes good organisation in primary schools. First of all, let’s look more closely at the structure of the school.

Internal and external structures

These are largely the elements and systems that naturally exist in schools and they consist of structures that are either internal or external (see Table 1.3).

Table 1.3 Internal and external structures that affect the school

Clearly there is a certain amount of interdependency between the two groups of structures. For example, class groupings, and subject groups such as sets for maths, will be dependent on the number of pupils on the school roll and the numbers in particular years. The number of teachers and the number paid above the basic pay spine will be, to a large extent, dependent on the amount of money in the school budget which will itself be dependent in the main on the numbers on roll in the school.

Organisational dimensions

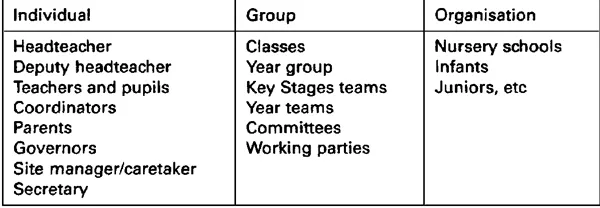

All schools are dependent on teams of individuals. However, individuals cannot work and perform effectively without effective groups or teams within the wider organisation. On this basis the organisation of a school could be represented as shown in Figure 1.1. The links between the individual, the group and the organisation can be extended even further to include LEAs, teacher unions, DfEE and OFSTED.

Figure 1.1 The organisational dimension

However far we extend these interrelationships it is important to emphasise one key issue: organisational dimensions of the school are management structures, and managing a school has to be first and foremost about individuals working together. This is where we have to start looking at different ways of organising the whole school.

WAYS OF ORGANISING THE WHOLE SCHOOL

Different types of organisation

Although schools have many similarities each is also unique. It is useful to look at some of the factors which most directly affect particular primary schools.

Size

Larger primary schools will often need a tighter and better-developed structure. They will tend to be more hierarchical and may well have departments, Key Stage teams and year teams that will not be found in smaller primary schools.

Designation

Obviously the title of the school will have considerable impact on how it is organised and what needs to be organised within it. The title is very important, whether it be nursery, infant junior or primary, county, community and/or denominational. Each will have its own influence on what can and cannot happen and what actually needs to take place for the school to be successful.

Leaders and led

All schools are hierarchical to some degree in that there is always a headteacher, teaching and non-teaching staff. In most schools there are deputy headteachers and several teachers may well have management or leadership allowances. Some schools will be very hierarchical, which can produce its own obvious problems. Others will be what is described as collegial. A general guide is that the larger the school, the more hierarchical is its management structure.

Design

School design can have an important impact on how it is organised. Some schools have classrooms that can be closed, while others are more open plan. Some are all on one site and others are split into several buildings. Long corridors, small dining rooms, the lack of sinks and temporary classrooms, for example, can influence what can be achieved relatively easily and what will be difficult to manage.

Culture

The way ‘things get done’ will affect how the school works, how efficiently it is managed and how adults and children relate to each other. This culture or ethos is often a product of history but it can be influenced by school size, how hierarchical the management style is and how the school is designed.

Cohesion

Any primary school is a mixture of many parts which have to come together in order to work effectively. The extent to which smaller groups and teams join together into a successful whole will influence the success of the school in maintaining and raising achievement, or not.

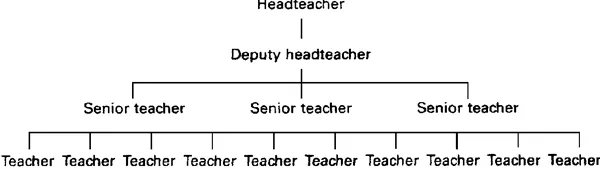

Figure 1.2 Hierarchical pyramid

Hierarchy and collegiality

Where a hierarchical structure dominates, there is likely to be more direction, more control and more commands from the ‘top’. The nature of this kind of structure will mean that the power is directed downwards and this will take place largely through a series of instructions with less room for discussion and debate. Although this kind of chain of command does not necessarily stop colleagues from working together, it can also make it more difficult. Collegiality on the other hand is more about professional colleagues cooperating, participating and delegating within a structure where working in decision-making teams is seen as important. The usual hierarchical pyramid looks like the one shown in Figure 1.2. Obviously, in smaller schools the pyramid will be much tighter and in many cases flatter because of the absence of a deputy or senior teachers.

In many small schools a hierarchical structure might be totally inappropriate (in fact it could be suggested that this kind of organisational structure is hardly ever appropriate in a primary school), but it is the case that some schools will be more collegial, some will be more hierarchical and others will be able to successfully combine the two.They will all, however, be organised in a way that aims to achieve effective results and to maintain good relationships between those who work in them.

Results versus relationships

Most organisations face a problem in striking a balance between achieving results and maintaining good relationships between those who work in the organisation. Schools are no different and it is often difficult to be both concerned about results and people.

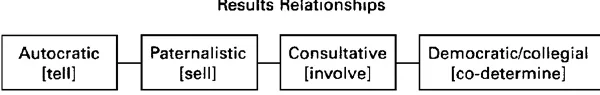

Figure 1.3 The results relationship continuum

There are basically three sets of needs that any manager has to consider. They are:

- what tasks need completing to achieve results;

- the needs of the staff team;

- the needs of the individual staff member.

Unfortunately, these three needs do not remain static but shift and change in terms of priority. Whatever type of structure you think would work best in your situation, it is important to determine where your school stands on a results-relationship continuum. Tannenbaum and Schmidt (1973) suggest that this kind of continuum has at its two extremes an autocratic and a democratic structure (Figure 1.3).

Processes will take place somewhere on this continuum. In many schools, individuals and teams will operate at one or several stages of the continuum.

Tell or talk

At the autocratic end, telling is the favoured method that managers use to organise what happens in the school. Orders are given and the expectation is that they are carried out. As we move along the continuum, the stages involve increasing amounts of dialogue as there has to be an attempt by managers such as heads and deputies to sell ideas to colleagues by persuading them to accept them. Involving colleagues, however, is more about heads and deputies consulting them about new ideas, changes in direction and different ways of working. It is this kind of consultation that marks a halfway point between autocracy and democracy. At the end of the continuum the management processes and the structures that are in place must recognise consensus as an effective way of both getting results and meeting the needs of people. Colleagues need to be able to co-determine what happens in the school through the use of teams of teachers and decision-making meetings.

School atmosphere

The perceptive but largely neglected Elton Report (1989), which was mentioned briefly in the introduction, includes the nebulous but useful phrase ‘school atmosphere’ (1989:89). The report emphasises that there were ‘differences in their [schools] feel or atmosphere’ (1989:88), and that ‘perhaps the most important characteristic of schools with a positive atmosphere is that pupils teachers a...