![]()

Part I

Maps and Positions

![]()

Chapter 1

Reframing Postmodernisms

Mark C. Taylor

Why is LA, why are the deserts so fascinating? It is because you are delivered from all depth there – a brilliant, mobile, superficial neutrality, a challenge to meaning and profundity, a challenge to nature and culture, an outer hyperspace, with no origin, no reference points. . . . The fascination of the desert: immobility without desire. Of Los Angeles: insane circulation without desire. The end of aesthetics.

(Jean Baudrillard)

I have come from the desert as one comes from beyond memory.

(Edmond Jabès)

Frames: Desert; Dessert. One word that is at least two – one spelling, two pronunciations; two spellings, one pronunciation. Desert; Des(s)ert. After dinner desserts – just or otherwise. Neither dinner nor not dinner, but a supplement. Something like a frame that repeats, while inverting, the hors d’oeuvre. No longer before but after the repas. Le repas: what is a pas that is a re-pas? Does the doubling of the k/not bind or rebind – ligare or religare? Desert . . . Des(s)ert . . . Des(s)erts. What is des(s)erted in the desert? Desert(s): site or non-site of wandering, erring – Vegas . . . vagus. Delivery from all depth . . . lights, pure light, absence of shadow? Or delivery to a certain re-pas that is beyond . . . le pas au-delà, where the absence of shadow is the shadow of spirit?

‘Postmodernism’ is, of course, a notoriously problematic term. As students of religion have become involved in debates about postmodernism, confusion has proliferated. For some postmodernism suggests the death of God and disappearance of religion, for others, the return of traditional faith, and for still others, the possibility of recasting religious ideas. I will not try to explain what postmodernism is, for it is not one thing. Indeed, from a postmodern perspective nothing is simply itself and no thing is one thing. Rather, I will contrast two postmodernisms in such a way that their differences become clear. I will approach this task by way of painting. More precisely, I will consider three examples of the painter/critic relationship: Barnett Newman and Clement Greenberg, Andy Warhol and Jean Baudrillard and, finally, Anselm Kiefer and Maurice Blanchot and Jacques Derrida. The contrasting aesthetic positions established by these painters and critics suggest alternative theological and religious perspectives. I am convinced that recent developments in the visual arts create new possibilities for the religious imagination.

Postmodernism, which is not simply an additional epoch or era following modernism, is inseparably bound to the modern. The term ‘modernism’ is as complex and as contradictory as postmodernism. The meaning of modernism changes from context to context and field to field. For example, while modern philosophy is generally thought to have started with Descartes’ work in the middle of the seventeenth century, the beginning of modern theology is usually dated from Schleiermacher’s Speeches on Religion in 1799. In the visual arts, modernism emerged during the closing decades of the nineteenth and opening decades of the twentieth centuries. Though an extraordinarily diffuse movement, different versions of modernism share a will-to-purity and will-to-immediacy that implicitly or explicitly presupposes a philosophy or theology in which being is identified with presence. The critic who raises the artistic methods of modernism to the level of self-consciousness is Clement Greenberg. In a highly influential essay entitled ‘Modernist Painting’, Greenberg writes:

I identify Modernism with the intensification, almost the exacerbation, of this self-critical tendency that began with the philosopher Kant. Because he was the first to criticize the means itself of criticism, I conceive of Kant as the first real Modernist. The essence of Modernism lies, as I see it, in the use of the characteristic methods of a discipline to criticize the discipline itself – not in order to subvert it, but to entrench it more firmly in its area of competence.1

So understood, modernism is, as Habermas continues to insist, an extension of the Enlightenment project. To be enlightened is not only to be critical but, more importantly, to be self-critical. ‘The task of self-criticism’, Greenberg continues,

became to eliminate from the effects of each art any and every effect that might conceivably be borrowed from or by the medium of any other art. Thereby each art would be rendered ‘pure’, and in its ‘purity’ find the guarantee of its standards of quality as well as of its independence. ‘Purity’ meant self-definition, and the enterprise of self-definition, and the enterprise of self-criticism in the arts became one of self-definition with a vengeance.2

Another term for the purity established by self-criticism is autonomy. An art form is pure when it is determined by nothing other than itself and thus is perfectly self-reflexive.3 From Greenberg’s point of view, modern art achieves aesthetic autonomy through a process of abstraction in which there is a gradual removal of everything that is regarded as inessential in a particular medium. In painting, the result of such abstraction is pure formalism in which all ornamentation and representation disappear. In semiotic terms, ornamentation and representation are signifiers that obscure pure form, which is, in effect, the transcendental signified. In other words, authentic art erases the signifier in order to allow the signified to appear transparently.

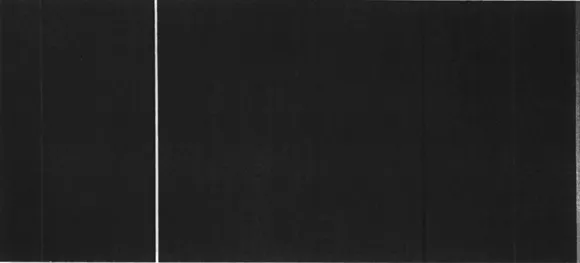

The will-to-purity that characterizes Greenberg’s aesthetic theory assumes a variety of forms in twentieth-century painting. For many artists, the search for aesthetic purity is actually a spiritual quest. Nowhere is the coincidence of painterly and spiritual concerns more evident than in the work of Barnett Newman. Newman’s signature canvases are monochromes that are interrupted by one or more vertical lines or ‘zips’. His titles underscore his spiritual preoccupations: Onement, Dionysus, Concord, Abraham, Eve, The Stations of the Cross, L’Errance, Moment, Not There – Here, Now, Be, Vir Heroicus Sublimis. The last five titles suggest an intersection of themes that recurs throughout Newman’s corpus: Moment, Here, Now, Being and the Sublime. In what might be regarded as his personal manifesto, ‘The Sublime Is Now’, Newman maintains that ‘man’s natural desire in the arts [is] to express his relation to the Absolute’.4 The goal of Newman’s artistic endeavour is to provide the occasion for the experience of the sublime. To experience the sublime is to enjoy the fullness of Being Here and Now – in the Moment. This moment is the Eternal Now, which, paradoxically, is simultaneously immanent and transcendent. It can be reached only through a process of abstraction in which the removal of figuration or representation creates the space for presentation of the unfigurable or unrepresentable. The (impossible) representation of the unrepresentable is sublime.

As is well known, Kant distinguishes the mathematical from the dynamic sublime. In both of its forms, the sublime is excessive; it marks the boundary between reason’s demand for totality and the imagination’s inability to deliver it. Anticipating the romantic preoccupation with nature, Kant argues that the dynamic sublime is encountered in the overwhelming power of nature. The dynamic sublime exceeds all forms. ‘In what we are accustomed to call sublime in nature’, Kant argues,

there is such an absence of anything leading to particular objective principles and forms of nature corresponding to them that it is rather in its chaos or its wildest and most irregular desolation, provided size and might are perceived, that nature chiefly excites in us the ideas of the sublime.5

Figure 1.1 Barnett Newman, Vir Heroicus Sublimis, 1950ñ1, Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Newman translates the Kantian dynamic sublime from nature to culture by reinscribing the power of formlessness in the purely formal experience of paint as such. Consider, for example, Vir Heroicus Sublimis. This immense canvas6 is painted a brilliant red, with five vertical stripes ranging in colour from cream and white to shades of pink and crimson. Newman intended his paintings to be viewed at close range. When one stares at Vir Heroicus Sublimis closely, the painting creates an halluncinatory effect in which it seems to engulf the viewer. The sense of direct participation in the experience of redness is deepened by the absence of any frame. Like many other modern painters, Newman leaves his canvases unframed. It is as though he wants to remove the frame to allow viewer and painting to become one. The perfect union of subject and object is the sublime experience of Onement. When Newman ‘seeks sublimity in the here and now’, Lyotard explains,

he breaks with the eloquence of romantic art but does not reject its fundamental task, that bearing pictorial or otherwise expressive witness to the inexpressible. The inexpressible does not reside in an over there, in another world, or another time, but in this: in that something happens. In the determination of pictorial art, the indeterminate, the ‘it happens’ is the paint, the picture. The paint, the picture as occurrence or event, is not expressible, and it is to this that it has to witness.7

In the event of painting, the will-to-purity becomes the will-to-immediacy.

This immediacy is the aesthetic version of the unitive experience that is the telos of negative theology. For Newman, the negation entailed in painting is, of course, abstraction. As I have suggested, abstraction removes every vestige of form and figuration in order to reach the formlessness of the unfigurable or unrepresentable. While the presence of figure is the absence of oneness, the absence of figure is the presence of oneness. Newman’s use of abstraction as a method of negation repeats one of the most important strategies employed by early Greek philosophers in their search for the original One from which all emerges and to which everything longs to return. Developing insights advanced in Plato’s Parmenides, Speusippus proposes a novel way of negation, which he labels aphairesis or abstraction. Aphairesis is intended to be an alternative to the well-established apophasis. Apophasis, the form of negation used in traditional negative theology, negates by stating an opposite. Complete identification would require an infinite series of negations. Aphairesis, by constrast, negates by abstracting or subtracting particular qualities from an entity. The penultimate aim of aphairesis is the essence of the entity under consideration; its ultimate aim is the essential One that underlies the many that comprise the phenomenal world. By moving from the world of appearance to the realm of essence, aphairesis functions like a ‘ritual purification’8 that allows the initiates to draw near the purity of the origin.

When Newman’s theoaesthetic project is placed in this context, it becomes clear that his work is a painterly version of one type of negative theology. As Harold Rosenberg points out, Newman attempts to ‘transform the canvas into the signified thing’.9 The pure signified, from which all signifiers have been removed, is nothing less than the Absolute. Newman conceives this Absolute in ontotheological terms that are characteristic of western philosophy and theology. The Absolute is the One in which Being is presence that is fully realized in the present.

Newman’s paintings not only suggest important parallels with negative theology but, if read somewhat differently, bear unexpected similarities to dialectical or neo-orthodox theology.10 During the first half of this century, Karl Barth and his followers developed an influential reformulation of Calvinist theology. Calvinism is, of course, rigorously iconoclastic; the transcendent God cannot be represented in images. In Barth’s theology, Calvin’s God reappears as the ‘Wholly Other’ who completely transcends nature and culture. In Barth’s early and more important work,11 the only way to relate to God is negatively, i.e. by denying the religious validity of all natural and cultural forms. Barth’s ‘No’, however, harbours a ‘Yes’. The negation of nature and culture is at the same time the affirmation of the God who is Other. Barth’s strategy of negation, which, it is important to note, he formulates at the precise moment non-objective painting appears, mirrors Newman’s method of abstraction. For Barth and Newman, the negation of representation is the affirmation of the unrepresentable. There is, of course, an important difference between Barth’s theology and Newman’s art. For Barth, the will-to-purity does not involve a will-toimmediacy. Complete union with the transcendent One is never possible and is forever delayed.

Abstract art and dialectical theology suffer a similar fate. The movement of negation or abstraction leads to a separation or even opposition between the aesthetic and the religious on the one hand, and, on the other, society, culture and history. Abstraction gradually becomes empty formalism. The ...