1

A SEARCH FOR SOURCES

Through the village of Anaploga the road becomes a track that takes you into one of the shallow ravines that divided up the ancient city of Korinth. Off to the left and westwards, skirting a field and grove of citrus trees (where must have been found the burials of the Geometric period I had been told about), brings you to the site of the American excavations. The publications from 1948 deal with what they call the Potters’ Quarter. It was here that the Korinthians produced many of the ceramic wares which, in their seventh and sixth century BC heyday, travelled right across the Mediterranean Greek world.

It was the spring of 1991. Wild flowers were everywhere. Hellmut Baumann’s pleasant little book (1981) Die griechische Pfanzenwelt in Mythos, Kunst und Literatur [Greek Wild Flowers and Plantlore in Myth, Art and Literature] tells all about the connections between many of the 6,000 native species and ancient Greeks. I was sure I found a species of larkspur, Consolida Ajacis, called Aias, after the hero at Troy. The story goes that after the death of Achilles, Aias and Odysseus quarrelled over his armour and weaponry, forged by Hephaistos. Aias won the argument, but Athena forced him to cede them to Odysseus. Driven mad at the affront, he committed suicide, falling on his sword. The Roman poet Ovid, in his Metamorphoses, tells of the transformation of his blood into a flower inscribed with the letters AI, the cry of anguish and mourning, the first letters of the hero’s name. And sure enough, the letter A, flanked both sides by the letter I, can be seen on the purple petals. A drawing on a tiny ceramic perfume jar, now in a museum in Berlin, is considered by some to be the earliest depiction of the story.

I was in Greece as part of my research into these pots, made in ancient Korinth in the seventh century BC. Technically termed Protokorinthian, they are part of various changes in Greek society and culture, times of the early city states and when many ideas were being borrowed from eastern design; hence the term Orientalising art. The perfume jars (aryballoi) are covered in tiny figures and many variants of lotus and palmette flowers.

The remains of the so-called Potters’ Quarter and all around were covered in wild thyme; some bee-hives were positioned up the ravine towards the rock of Akrokorinthos, presumably to take advantage of this. There was not much to see, as I had expected. Excavation had taken place to investigate the defensive circuit wall when considerable quantities of pottery attested to a site of manufacture. But the excavations only investigated a narrow strip parallel to the outer wall, so there are no complete plans of the area, only enough to give a rudimentary understanding of the potteries; this is compounded by confusing recording and descriptions—it is difficult to work out what came from where. They may not even have been specialised, purpose-designed potteries. I checked out a cutting in the bed-rock which the present Head of Excavations in Korinth, Charles Kaufmann Williams II, reckons is evidence that the city may have been walled at an early date, in the seventh century BC. As well as being in the forefront of pottery design, Korinth was pioneering new settlement planning and military organisation. The Greek helmet that everyone first brings to mind—completely covering the head, with cheekpieces and nose-guard for the face, eyes cut out from sheet-metal, crest nodding on top—was a Korinthian invention.

Figure 1.1 The Potters’ Quarter, Korinth

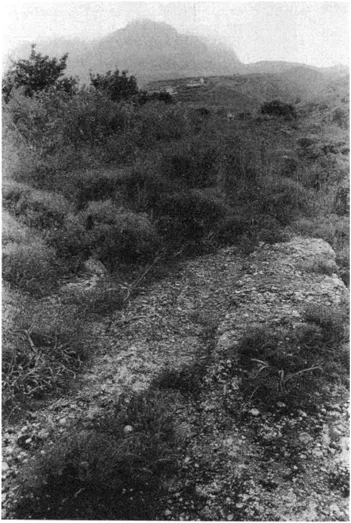

The modern town of Korinth is in the angle of the Isthmus and the northern coastline of the Peloponnese, the southern mainland of Greece. It was completely wrecked by an earthquake in 1928 and looks homogeneously modern with its antiseismatic buildings; tourist guide books tell you to avoid the town. A few miles away towards the great rock Akrokorinthos and on its northern slopes is Archaia Korinthos, the small village of Old Korinth. The central square is right by the centre of the ancient city.

Figure 1.2 Korinth from Akrokorinthos. Nineteenth-century engraving. (Courtesy of the Museum of Classical Archaeology, Cambridge)

Korinth was proverbially wealthy. Thucydides wrote in the fifth century BC:

Because the Korinthians had their city on the Isthmus they have always had a market. In ancient times the Greeks travelled through the Korinthia to make contact with each other rather by land in and out of the Peloponnese than by sea, and the Korinthians were powerful through their riches, as is shown by the ancients; for they called the place wealthy.

Its reputation in the ancient world was one of this smart opulence and business finance, combined with commercialised pleasure along the lines of Las Vegas. Osbert Lancaster calls the ancient Korinthians the advertising men and motor-car salesmen of the Greek world. Korinth was, however, known as the place where painting was invented. At the time of its capture by the Romans (Lucius Mummius razed the city and killed or sold its inhabitants into slavery in 146 BC), Korinth was stuffed with works of art. Pliny as connoisseur and antiquarian later collected Korinthian bronze statues. One of the earliest works of Korinthian art, which retained its celebrity in later times, was the chest of Kypselos, tyrant of Korinth in the seventh century BC, made of cedar wood and adorned with figures. It was dedicated to Zeus at the sanctuary of Olympia where Pausanias, the Roman writer of the most famous tourist guide to Greece, saw it and described it in minute detail.

Korinth had various reputations as a centre of craft and design. Athenaeus writes of rich garments from Korinth and there is mention in Antiphanes of Korinthian stromata—rugs or blankets. Remains of a large dye works (vats and concrete dying floors) have been found in the city centre. Korinth was also famous for perfumeries. Plutarch, writing in Greek in the first century AD, recalls that an exiled tyrant of the Sicilian city of Syracuse, Dionysios II, whiled away his time in the famous perfumeries of the city. The pots I was interested in are certainly small oil jars. Did they indeed contain perfumed oil, as has long been supposed? Some scientific studies have found traces of resins appropriate to perfume in similar types of small pot. Humphry Payne, a British archaeologist, sometime Director of the British School at Athens, wrote in his great book on Korinthian pottery, Necrocorinthia, that one aryballos, upon being opened, smelled of scent two thousand years old!

The project which brought me to Greece on this occasion concerned Korinthian manufacture. The aryballoi of seventh-century Korinth are an important class of artefacts to Classical archaeologists for various reasons. As I have already mentioned, they are at the forefront of changes in design in the late eighth and seventh centuries BC. Art historians consider this ‘Orientalising phase’ a crucial one in the development of Greek art. Aryballoi have been collected by the great art museums for nearly two centuries. I had already visited collections in London and Boston and spent much time working through the series of books Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum, which record and illustrate the Greek pots to be found in museums around the world.

The style of these pots is very distinctive, regularly changed, and is easily recognised. There is a clear sequence through time from fat and globular shaped to pointed aryballoi. This makes an aryballos a good index of the relative chronology of an excavated archaeological context, such as a grave, temple rubbish dump, or whatever, within which it was found—a corpse accompanied by a globular aryballos was most likely laid to rest before another found with a more pointed base. And aryballoi have consistently been found in the cemeteries of early Greek colonies in Sicily and southern Italy; in antiquity they were taken to religious sanctuaries and out to colonies and settlements in the west, Magna Graecia (Great Greece as southern Italy came to be called). Absolute dates of foundation seem calculable for some colonies from references in later Greek authors, particularly Thucydides. So Protokorinthian pottery provides a chronological scheme for the late eighth and seventh centuries BC, and one which is so useful because aryballoi turn up all over the Greek world, enabling cross referencing of disparate stylistic groupings and local relative sequences.

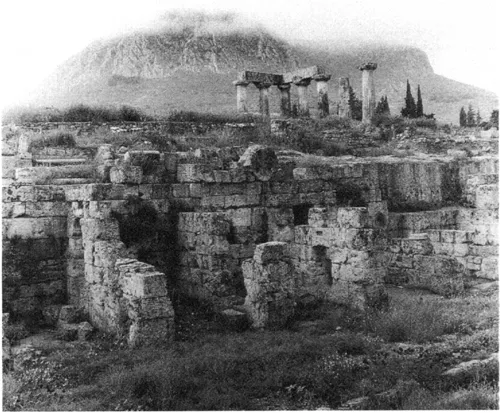

Figure 1.3 Temple of Apollo, Korinth, with the North Market in the foreground

I was interested in a wider question: why did the Korinthian potters start drawing people and animals and flowers upon these new designs of pots? Greek art is so focused on the human body. I wanted to know how this interest started. Why did the Korinthians need images like these?

I had arrived in Korinth with a friendly Aegean prehistorian, a Greek Cypriot (who looked like Telly Savalas) based in the British School of Archaeology at Athens. He was interested in the prehistoric remains which predated the city state, or polis of Korinth. Together we were going to approach the Director of the Korinth excavations during this busy excavation season. Charles Williams was working on a part of the city centre, to one side of the Roman forum, in Frankish levels. One of the American graduate students told him of our arrival. He helpfully supplied an offprint of an article of his about the early development of the city, told me of the problems and inadequacies of the excavations of the Potters’ Quarter, and took me over to the dig house. In this smart villa is a small working library. There are various doctoral dissertations on the shelves forming a record of a coherent research programme, coherent because most theses were produced at the suggestion of a few Directors of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. They certainly benefited considerably from their patronage. And, as if to remind me, the chairs were labelled with the names of the excavating professors: Blegen and Broneer and others. Photographs of the same decorated the walls.

The foreign schools of archaeology and Classics in Athens have dominated excavation in Greece over the last 150 years. Their activities have been restricted for some time now, but the financial resources of the Americans still have great pull. Excavations continue, notably at Isthmia, down the road from Korinth and originally one of its sanctuaries (to Poseidon), and on the prestigious site of the market place (Agora) of Athens. The big excavations in Greece have concentrated on the centres of the famous cities, and on the great sanctuaries such as Delphi and Olympia. A couple of years later I heard Mr Williams (as I was told by a knowing research student to call him) give a fascinating talk reconstructing the architectural features of a Roman building in Korinth.

I spent some time exploring what little was left of the Greek city. The walk over to the Potters’ Quarter from the city centre was not a short one; as I indicated, it is beyond the next village to Archaia Korinthos. It is clear that the early ‘city’ was not at all the conventional image we have of urban settlement. There were few scattered sherds in the cultivated fields by Anaploga, before the Potters’ Quarter at the circuit wall—something inconsistent with densely populated areas, however ancient (ceramic materials are notoriously durable). The consensus is that Korinth began as an association of scattered villages, much as the region is today.

Another favourite type of site has been the cemetery. I had already read of the North Cemetery at Korinth, again excavated by an American team. lan Morris and others have adopted approaches to cemetery analysis taken in prehistoric archaeology with the aim of using archaeological evidence to reconstruct the structure of ancient society. Not here an interest solely in the artefacts found buried with the dead, nor in city centre architecture, nor in the fine dedications found in religious sanctuaries. The idea is that the pattern of finds in a cemetery reflects the organisation of society. Lack of finds and poor evidence of dates meant that Morris couldn’t do much with Korinth.

Before coming out to Korinth I had spent some time in Athens, at the British School, using its library and visiting the National Museum with its collections of Protokorinthian pottery. Most foreign archaeologists use the schools in Athens; they are legally required to be attached to a foreign school if they are to do any serious work beyond intelligent tourism. The Assistant Director of the British School had written, for example, after I had registered that year, asking whether I needed any permits or museum passes. Since most of the material I wished to look at was now in Italian museums, I had declined the offer.

The British School at Athens is an erstwhile colonial establishment of learning, set in gardens shared with part of the American School of Classical Studies, its bigger neighbour, in Kolonaki, the embassy district of Athens. Let me try to give some idea of the character of the place. It was founded in 1886 after high-level negotiations and initiatives involving the Prince of Wales, Gladstone, Lords Salisbury and Rosebery, the academic Jebb, and Macmillan from the wealthy publishing family. The Greek government granted some land on the slopes of Mount Lykabettos, a large house was built; and Francis Penrose, member of the old aristocratic Society of Dilettanti, became the first Director.

The school is now centred upon the hostel; the old house has become solely the Director’s. Here is to be found the accommodation for the students, dining room, offices and library. Photographs of the Queen and Prince Philip greet you in the foyer where is also to be found the visitors’ book (lots of distinguished names of academics and others). The offices house a secretary and the Assistant Director who is responsible for the day-to-day management of the place (surveying tripod by the door). The common room is known as the Finlay Library (still containing many old books on topographical subjects). I remember from earlier visits late afternoon drinks (iced tea and coffee) on the terrace. The ouzo flasks were empty on this visit and the chairs in sorry repair. The fine Penrose Library was the reason why I was at the school, checking up on books and periodicals. It has been said that if it weren’t for the library, the school would be little more than a youth hostel (albeit a smart one with plenty of connections, a nice garden and tennis court). There is also the Fitch Laboratory, for archaeological science. This has become an expanding and important field. Particularly popular are characterisation studies: scientific determinations of the character of archaeological materials such as ceramics (knowing the precise composition of a clay can help establish where it came from, if a map can be made of clay deposits).

There is a community at the school all year round. Students arrive from parent universities in Britain to follow their various research projects, using the library and the School as a base. The school has its own students (funded independently), including the Greek government scholars and British students supported by Greek bursaries (notoriously meagre). As I have mentioned, the visitors’ book records many more temporary stays by affiliated students such as myself.

Regular lectures are held here and also in other foreign schools with which there is regular contact. During my short stay in 1991 an invitation to an evening lecture and reception came from the Goulandris Museum. The Canadian school was presenting its year ‘s work at this private museum centred on the art collection of a Greek shipping millionaire. I felt distinctively underdressed among the social set of Kolonaki.

A small portrait of Humphry Payne, another Director of the school in the 1930s, hangs on the wall of one of the rooms in the library (named after him). Just below is shelved a book, a general account of ancient Greece by an author now obscure, whose inside cover is inscribed ‘winner of the Leslie Hunter Prize for an essay in Classical Archaeology—Winchester July 1922—signed M.J.Rendall (Informator)’. It belonged to John Devitt Stringfellow Pendlebury, Curator of the British School’s outpost at Knossos on the island of Crete, 1929–34. Various other distinguished ex-members of the school have given their books to the library. A sun-tanned young lady, fresh in from Egypt, told me she was writing Pendlebury’s biography. Having read Classics at Oxford, she was grateful to her family whose wealth gave her the opportunity to travel and here record the life and times of this British archaeologist who had immersed himself in Aegean prehistory and had been shot by the Germans in 1941 for helping with the resistance. She was off to Crete for a party commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of his death.

A Greek government scholar was interested in the ancient Greek army. He read me a passage from an early Greek poet and mercenary, Archilochos, with some reference, he explained, to short cropped hair. Having been in the marines himself he felt he sensed what Archilochos was on about in his lyrics. I took this to be representative of a relatively new interest, after the work of Victor Hanson particularly, in the experience of ancient soldiering; so much effort has been invested in the history of tactics and battles and campaigns of conquest, but little in understanding the life of the ordinary soldier.

Others were engaged in studies of the imagery on Mycenaean pots (second millennium BC bronze age) and Mycenaean ceramic animal figurines. I asked what they thought they were about. ‘I must leave interpretation to someone else’, a student from Basel told me. Not all were academic researchers, however: someone was seated in the spring sunshine on the roof of the school, painting pictures of Greek scenes.

The weekend before I left, many of the people at the school were off to the Mani, a relatively remote part of the southern Peloponnese, to immerse themselves in the rural Greece of old. They were after the experience of authentic Greece, the fascination of the peasant medieval world in the late twentieth century, and well away from the tourist trail. So many of us must feel this urge to escape commercialised and conditioned experience, but they seemed to be setting out on an anthropological trip whose character concerned me. There were strong undercurrents of Rousseau—observing noble savages, aboriginal Greeks, and a sense of voyeurism. These members of the British School were in a foreign country which nevertheless was culturally familiar to them through their studies, through their institutional links and interests. But Greece in the remote south was an opportunity to escape to experience and learn about the unfamiliar, or another premodern time. Learning can be seen as a process of absorption. It may be conceived that knowledge of the past lies in meticulously observing, measuring and describing pottery. (A Japanese archaeologist in Athens described to me his seven-year project of recording all marine scenes, and especially those containing octopuses, upon Mycenaean pots. He had devised a framework which fitted around a pot and gave a fixed and ...