![]()

1

Historical Considerations

Arterial hypertension, high blood pressure (BP), has been described as a clinical entity only since the early 20th century when the works of Riva-Rocci1 in 1896 and Korotkoff in 19052 led to a simple, noninvasive method of measuring BP in man. Actually, the knowledge that the circulating blood exerts an hydraulic force goes back to the observations by the Reverend Stephen Hales in 1733. Hales, in a classic paper,3 described inserting a brass pipe into the femoral artery of a mare, then connecting it to a vertical glass tube and noting that “the blood rose eight feet and three inches (i.e., 183 mm Hg) above the left ventricle of the heart.” Moreover, although the relationship of the kidney to vascular disease originated from the writings of Bright on nephritis in the early 19th century,4 it was not until 1896 that Albutt suggested the existence of an “anterenal” form of hypertension.5 By 1920, the differentiation of primary, or essential, hypertension from that associated with glomerulonephritis had been established. In the 1930s and 1940s the renal hemodynamic changes in hypertension were clarified indicating that the kidney developed secondary functional and pathologic changes from hypertension as well as being involved de novo in the origin of certain forms of hypertensive disease. 6, 7

Nevertheless, little change occurred in the concepts of the significance of an elevated BP and its management during this period. Hypertension was diagnosti-cally and prognostically divided into benign and malignant types; the former was typified by minimal target organ impairment and generally was well tolerated, the latter by severe renal and ophthalmologic changes (i.e., rapidly progressive renal failure and fundal hemorrhages, exudates and papilledema). Many believed that primary hypertension of the “benign” type was indeed “essential” to maintain bloodflow through aging arteries and hence in fact the origin of its name. Specific therapies for hypertension did not exist, either for the forms secondary to nephritis nor for the malignant phase of the disease and certainly not for the so-called benign essential type.

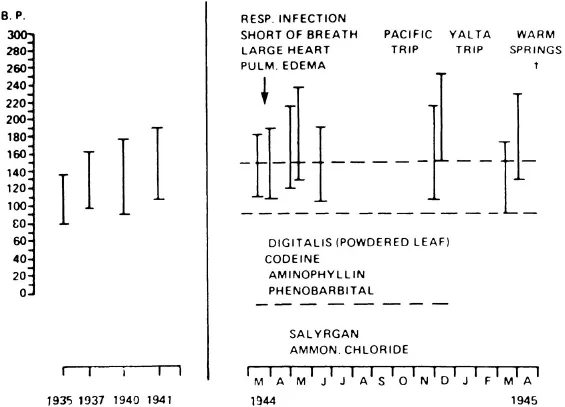

This state of affairs in the therapy of hypertension is impressively illustrated in the medical history of Franklin D. Roosevelt, U.S. President from 1932 until his untimely death in 1945 at age 63 from a massive cerebral hemorrhage. That Roosevelt had crippling poliomyelitis was well known, but less attention was given to the fact that he had progressively more severe hypertension throughout his 14 years in office. His course was “benign” during most of this time, but in 1944 he developed congestive heart failure, by now recognized as a complication of his hypertension, and was treated with digitalis and mercurial diuretics, then the “state of the art” for heart failure. However, his BP remained markedly elevated and led to his central nervous system (CNS) catastrophe a year later, as the terminal complication of his hypertension. Although Roosevelt was perhaps the “most important person” in this country, and perhaps the world, at this time, and had available to him the “best of medical care,” no specific therapy for hypertension per se was given to him, for the simple reason that no therapeutic agents to safely lower BP were then available8 (Fig. 1.1).

Fig. 1.1 Course of blood pressure in Franklin D. Roosevelt from 1935 to 1945 as extracted from an article by Bruenn, H. G. Annals of Internal Medicine (1970; 72:579–591).

I became interested in hypertension while at the Department of Medicine at the University of Cincinnati in 1948, where I completed my training in internal medicine as a fellow with Dr. Eugene B. Ferris. Dr. Ferris’ research interests were broadly in the field of autonomic nervous system (ANS) control and this led to studies concerned with the sympathetic nervous system in hypertension. There were few formal training programs in the various subspecialties in medicine at that time; I suppose in modern day parlance I would be considered a fellow in general medicine. I had come back to New York City in 1947 after military service; prior to the military, I had several years of training in internal medicine, and on my return to New York City I spent approximately 9 months as a resident in psychiatry with Dr. Howard Potter of the Long Island College of Medicine and the Kings County Hospital in Brooklyn. This latter experience led to my interest in combining internal medicine and psychiatry in what was then the emerging area of psychosomatic medicine, a discipline that Dr. Ferris and others in the Departments of Medicine and Psychiatry at the University of Cincinnati were developing. As a model for psychosomatic research, they used hypertension, in which the effects of stress on the vascular system were of particular interest.

Actually, my interest in hypertension probably went back further to medical school in the early 1940s when a close relative who had hypertension also had nephrolithiasis affecting one kidney. At that time, Goldblatt’s work on producing hypertension by renal arterial constriction was just beginning to attract clinical attention.7 Actually, Tigerstedt and Bergman9 discovered renin as a pressor agent arising from the kidney in 1897, but it was in the 1930s that Goldblatt performed his experiments in the dog in which he showed that the ischemic kidney could cause hypertension. It took at least 20 years after Goldblatt to work out the renin-angiotensin cycle and its relationship to ischemia, and not to parenchymal disease, of the kidney. Meanwhile, clinicians were intrigued by the possibility of “curing” hypertension by removal of a unilaterally diseased kidney of any type; hence the interest in a unilateral nephrectomy in my aforementioned relative. Fortunately, a more astute and thoughtful internist countered the enthusiasm of the urologist, and the relative had a simple nephrolithotomy, but kept his kidney and his mild hypertension, without further progression for many years.

I stayed in Cincinnati for 3 years, working primarily on mechanisms of BP control, using ganglionic blocking agents that had just been developed, as the tools for these studies. The effect of stress on BP, particularly in regard to perpetuation and progression of the disease, was also a prominent part of our work. Toward the end of this training, we did undertake early drug studies helping to develop some principles of clinical pharmacology, and more is discussed about these experiences later. Mostly our work was not in therapeutics per se. We were not further advanced from the status of therapy as described in my earlier comments about the management of Roosevelt’s hypertension.

These comments thus lead to the reasons I am writing this book and constructing it in a manner related to the research in hypertension since the 1940s and 1950s. When I began to study hypertension in Cincinnati in 1948 some mechanisms were understood but the rennin–angiotensin system was a speculative concept, the role ofthe various adrenal hormones was not known, and therapy aimed at any specific mechanism was not available. Perhaps the exception was the procedure of sympathectomy that was popular for severe hypertensives in the 1940s and was based on partial knowledge of the role of the sympathetic nervous system in hypertension. Results of this procedure were disappointing, although part of our work in Cincinnati was to develop techniques to predict who might be more amenable to this drastic surgery (i.e., by determining the acute effects of sympatholysis by gangli-onic blocking agents on BP). However, the operation was largely abandoned by the 1950s.

Since the 1940s and 1950s, progress in understanding and treating hypertension has been remarkable. Although perhaps not as dramatic as the “antibiotic breakthrough” in infectious disease, this progress nevertheless has made a major contribution to health care as concerns quality of life, prevention of disability, and mortality. Hypertension and hypertensive disease had been a “silent scourge” when I first became involved in 1948, but in 1996, it is an industry. Research has expanded into the fields of epidemiology, endocrinology, surgery, pharmacology, behavioral medicine, and others. Therapeutic accomplishments have made hypertension a leading source of income for the pharmaceutical industry and the field of clinical pharmacology really originated with the development of drugs used to treat hypertension. Increasingly, specific drugs to treat specific mechanisms that raise BP have come from the laboratory to the bedside. Many physicians of various specialties treat hypertension today; it is a disorder commonly and frequently treated in the outpatient practices of family practitioners, general internists, cardiologists, and even many of the other subspecialties within internal medicine.

Throughout all these developments, a constant awareness has been present that emotional stress, both from within the individual as well as from environmental sources, plays a role in the predisposition, precipitation, and perpetuation of hypertension. Arguments have been put forth that such stress may be the major cause of at least some forms of hypertension, to the thesis that although some effect is present from stress, it is only a minor perturbation of no significance in the overall pattern of the disease. Advocates of stress theory may be biased by a lack of detailed knowledge or experience with the physiology and biochemistry involved in the establishment of this disorder but on the other hand, those who deny the importance of stress factors may be unaware of the large body of data that indicate the role of these factors in any comprehensive understanding of hypertension.

Our own approach to hypertension follows from the Mosaic Theory, which the late Irving Page brilliantly advocated for many years.10 In this concept, multiple factors can be invoked in understanding the etiology and management of hypertension, with the strength of the individual factors varying depending on genetic background, acquired diseases, and environmental influences. Stress can be involved in predisposition by affecting a genetically programmed person, in precipitation by supplying the stimulus to bring the disease to a clinical level, and in perpetuation by maintaining or exacerbating the clinical disease. Accordingly, in this book I attempt to integrate what is known about the effects of stress on BP with the overall mosaic of the disease, hypertension, so as to underline where, in Page’s

Mosaic, these factors are best fitted. In this effort, I make use of the aforementioned “three Ps”—predisposition, precipitation, and perpetuation—as part of the framework for this integration, a concept developed by the late I. Arthur Mirsky as a device by which to study behavioral impacts in psychosomatic disease.11

References

1. Riva-Rocci S. Un novo sfigmanometro. Gazz Med Torino. 1896;47:981–1017.

2. Korotkoff NS. On methods of studying blood pressure. Izyestiya Voenno-Med Akad. 1905;11:365–367.

3. Hales S. Statical essays: Containing hemostatics; An account of some hydraulik and hydrostatical experiments. 2nd ed., London: Innys and Mandy; 1740:1–3.

4. Bright R. Tabular view of the morbid appearances in 100 cases connected with albuminous urine with observations. Guy’s Hosp Rep. 1836;1:380.

5. Albutt TC. Senile plethora or high arterial pressure in elderly persons. Trans Hunter Soc. 1895;77:38.

6. Goldring W, Chasis H, Ranges HA, Smith HW. Effective renal blood flow in patients with essential hypertension. J Clin Invest. 1941;20:637.

7. Goldblatt H, Lynch J, Hanzal RF, Summerville NW. Studies on experimental hypertension. I. The production of persistent elevation of systolic blood pressure by means of renal ischemia. J Exp Med. 1934;59:347.

8. Bruenn HG. Clinical notes on the illness and death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Ann Intern Med. 1970;72:579–591.

9. Tigerstedt R, Bergman PG. Niere und Krieslauf. Skand Arch Physiol. 1898;8:223.

10. Page IH. The nature of arterial hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 1963;111:103–115.

11. Mirsky IA. Physiologic, psychologic and social determinants in the etiology of duodenal ulcer. Am J Dig Dis. 1958;3:285–314.

![]()

2

Reactivity and Blood Pressure

Acute Blood Pressure Reactivity

The most obvious reason for implicating stress as a factor in hypertension is the observation of the lability of BP which occurs with almost any perturbation of the organism. Reactivity has been defined as the individual’s propensity to display BP changes when encountering stimuli that are engaging, challenging, or aversive. Such stimuli may arise from the environment or from within the individual, and may be pleasant as well as noxious.

Reactivity should be differentiated from variability. Variability is the tendency for BP to vary on repeated measurement over time—minute to minute, daily, weekly, and so on; it is a biological phenomenon with many causes, whereas reactivity is the response of the BP to stimuli. Reactivity can be depressor as well as pressor; in fact, as is discussed later, the reduction of BP that occurs with certain behavioral manipulations and therapies is an example of the converse of the pressor response to stimuli, which is then a depressor response.

Reactivity has been measured in the laboratory by a wide variety of stimuli, both physical and psychological. The former include the cold pressor (CP) test, ischemic pain, intravenous injections—ranging from saline (placebo) to various catecho-lamines—exercise, smoking, hypercarbia, hyperventilation, and so forth. Psychological stimuli that have been popular in various studies include mental arithmetic in various forms, mirror tracing, the Stroop Color-Word test, role-playing by the investigators, interviews concerning known stressful topics, video games, speech tasks, and introduction of coping problems.1 The reactivity response is usuallymeasured as the arithmetic difference between the baseline BP and the estimated peak of the stress reaction, but in some studies a baseline adjustment is considered by using a percentile response. Manuck, in his recent writings considered that such a b...