eBook - ePub

Human Ecology

The Story of Our Place in Nature from Prehistory to the Present

- 230 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This new edition of a widely adopted primary and supplementary text explores human adaptations to environments over time. It is biologically and culturally sophisticated, drawing on an impressive array of archaeological and paleontological research. Campbell proceeds from earlier, simpler biomes to later, more complex ones, examining selected aspects of the prehistory and history of the human species. Human Ecology offers a succinct introduction to the history of these adaptations within ecosystems: a shared concern among anthropologists, biologists, environmentalists, and the general reader.In the years since this book was first published, the problems that the human species has faced have become more serious. As predicted, world population has rapidly increased, and with it starvation, malnutrition, and disease. Our precious environment is being devastated. In particular, the tropical rain forests, our richest resource, are being cut and burned at an alarming rate with the accompanying degradation of the forest soils. Their flora and fauna, including their human inhabitants, are being destroyed. All this is being done for short-term financial gain without any long-term planning or understanding of the risks involved.There are no simple and humane short-term solutions to the central problem of increasing population pressure. In the long-term, the only hope of making possible a life of quality for all, rather than a life of starvation and squalor, is through education. It is essential that we understand the limits that exist to the earth's productivity and the overriding importance of maintaining richly diversified fauna and flora. If we understand how we arrived at this life-threatening situation, the resolution will become clear. Non-violent and viable solutions do exist and can be implemented, but the human race first must understand and face up to the nature of its frightening predicament.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Human Ecology by Bernard Campbell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

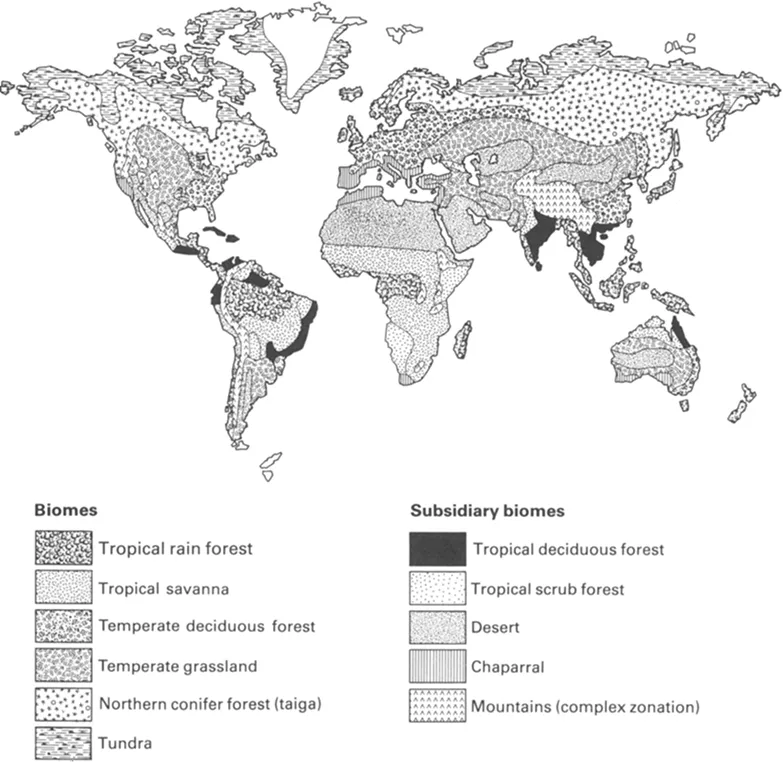

Figure 1.1 Map of world biomes. The biomes indicated here are fairly stable zones and can be mapped in some detail. Note that only the tundra and northern coniferous forest have some continuity across the northern hemisphere. Other biomes are isolated in separate geographical regions and therefore may be expected to carry ecologically equivalent but taxonimically unrelated species.

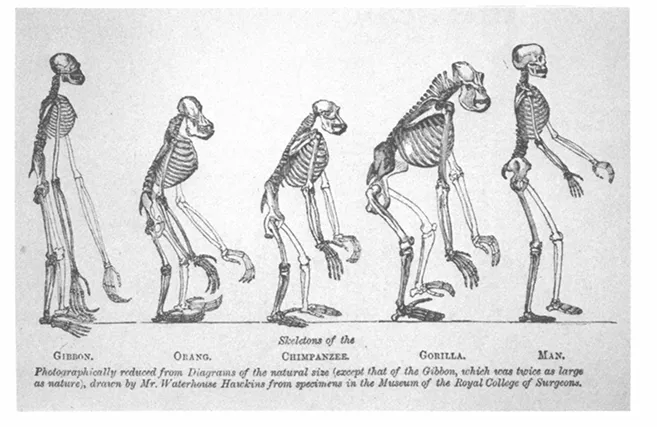

Figure 1.2 When the Ońgin of Species was published Darwin was not aware of any fossil evidence for human evolution and did not discuss the question. The evidence from comparative anatomy, however, was very strong and as a result many biologists came to accept the hypothesis of human evolution. Darwin’s friend and supporter T.H. Huxley published a book entitled Man’s Place in Nature in 1863 and in it he wrote ‘Whatever part of the animal fabric might be selected for comparison, the lower Apes (monkeys) and the Gorilla would differ more than the Gorilla and Man.’ These drawings are done to the same scale except for the Gibbon which is twice natural size. (From T.H. Huxley, 1863)

EVOLUTION AND ENVIRONMENT

Future historians will surely recognize that Charles Darwin’s book, published in 1859, was one of the most important ever written. On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection1 not only presented the theory that animal and plant species had evolved over millions of years from relatively simple ancestral forms, but it also described an hypothesis which explained how this process actually came about (Fig. 1.2). The idea of organic evolution or 'the transmutation of species', was not in itself new and has been commonly linked with the names of the French naturalist Lamarck as well as with Charles Darwin’s grandfather Erasmus Darwin; but the concept of natural selection, which explained the process, was original and of extraordinary importance, as it gave the theory a basis—a logical structure which made it increasingly acceptable to those concerned with biology and natural history.

Figure 1.3 (Left) Charles Darwin in his 66th year. Darwin lived comfortably at home at Down House in Kent with a substantial private income so that he could devote most of his time to research and writing. An intermittent invalid, he wrote ‘Even ill-health, though it annihilated several years of my life, has saved me from the distractions of society and amusement.’ He lived to the age of 73. (National Portrait Gallery)

Figure 1.4 (Right) Alfred Russel Wallace, a Welsh botanist, was a complete contrast to Darwin in both background and character. Unlike Darwin, Wallace earned his living by collecting rare tropical plants and animals for private collectors and museums. As a result, he travelled more widely than Darwin in both South America and Southeast Asia. Later in life he wrote a number of books on geography and evolution, but although of considerable interest they do not have the originality and intellectual integrity of Darwin’s writings. While Darwin lost his religious belief, Wallace remained a religious man throughout his life. (National Portrait Gallery)

Although Darwin formulated the idea of natural selection first, in 1938, another naturalist, Alfred Russel Wallace, arrived at the same concept independently in 1858. By an extraordinary coincidence, Wallace sent a short account of his ideas to Darwin early in 1858, and as a result their joint paper was presented to the Linnaean Society in London, later that year (Figs. 1.3, 1.4).

Both Darwin and Wallace had travelled widely and observed in great detail the variation that exists within animal and plant species. Members of species, they noted, are not identical, but they vary in size, strength, health, fertility, longevity, behaviour, and many other characteristics. Darwin realized that humans use this natural variation when they selectively breed plants and animals; a breeder allows only particular individuals possessing desired qualities to interbreed.

Both Darwin and Wallace saw that a kind of selection was at work in nature, but they did not know how it worked. An understanding of the means by which selection operates in nature came to both from the same source. The first edition of An Essay on the Principle of Population by an English clergyman, T.R. Malthus, had appeared in 1798.2 In his book, Malthus showed that the reproductive potential of humankind far exceeds the natural resources available to nourish an expanding population.

In a revised version of his essay, published in 1830, Malthus began: Tn taking a view of animated nature we cannot fail to be struck with the prodigious power of increase in plants and animals . . . their natural tendency must be to increase in a geometric ratio—that is, by multiplication.’ He continued by pointing out that, in contrast, subsistence can increase only in an arithmetical ratio. ‘A slight acquaintance with numbers will shew the immensity of the first power in comparison of the second.’ And he had written in 1798, ‘By that law of our nature that makes food necessary to the life of man, the effects of these two unequal powers must be kept equal. This implies a strong and constandy operating check on population from the difficulty of subsistence.’ As a result he argued that the size of human populations is limited by disease, famine, and war and that, in the absence of 'moral restraint', such factors alone appear to check what would otherwise be a rapid growth in population.

Both Darwin and Wallace read Malthus’ essay, and, remarkably, both men recorded in their diaries how they realized that in that book lay the key to understanding the evolutionary process. It was clear that what Malthus had observed among human populations was indeed true for populations of plants and animals: their reproductive potential vastly exceeds the rate necessary to maintain a constant population size. Darwin and Wallace both realized that the individuals that do survive must be in some way better equipped to live in their environment than those that do not survive. It follows that in a natural interbreeding population any variation would most likely be preserved, or passed on to future generations, that increased the organism’s ability to produce fertile offspring, while the variations that decreased that ability would most likely be eliminated.

Around these ideas Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace formulated a theory of evolution by natural selection. The theory is not difficult to understand and may be stated as follows:

- Organisms produce far more offspring than required to maintain their population size, and yet their population size generally remains more or less constant over long periods of time. From this fact, as well as from observation, it seems clear that there is a high rate of mortality among immature individuals.

- Individuals in any population show much variation, and those that survive do so to a large extent because of their particular characteristics. That is, individuals with certain characteristics can be considered better adapted to their particular environment.

- Since offspring resemble their parents closely, though not exactly, successive generations will maintain and improve on the degree of adaptation by gradual changes in each generation.

This process of variation, and selection by the environment of better-adapted individuals, Darwin called natural selection and the change in the nature of the population that follows upon such selection is the process of organic evolution. The same process occur among both plants and animals. The process of evolution is extremely slow, and to be accepted, the theory required the Earth to be of great age. Darwin and Wallace’s theory could not have been accepted by the generations taught by Bishop Ussher, who believed the Earth to be less than 6000 years old. But in his book, Principles of Geology (1830-33), Charles Lyell3 had provided the time dimension required for evolution to work.

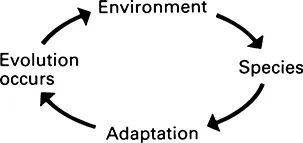

The first important thing to note here is that the creative process of natural selection is driven by the environment; ultimately by the climatic changes which inevitably occur, and by the immense variety of different environments which the planet Earth carries. Once the process of evolutionary change and the radiation of species is underway, further environmental change due to the appearance of new animals and plants is inevitable, and as the process continues and species multiply, the rate of change tends to accelerate (Fig. 1.5). Thus the key to evolutionary change is the interaction of the environment and the organisms which occupy it. The environment, with its ever-changing climatic, mineral, and organic components, brings about the evolutionary process through its effect on heritable variation and is a primary factor in the creation of the multitudinous species of animal and plant life.

Figure 1.5 Because the environment is acting on all existing species and reducing the reproductive capacity of those individuals less well adapted, each species evolves, and in turn brings about changes in the environment of all other species. This is an example of a positive feedback loop where the processes of change in one component (the environment) bring about accelerating changes in the system as a whole.

The second point to note is that it is now clear, as Darwin surmised, that all nature is one in the very particular sense that animals and plants reproduce and grow by the same genetic mechanisms. Their reproductive chemistry is basically similar. Genes, in the form of DNA coding bearing important biochemical characters, can be successfully transferred between a bacterium and a mammal and such genes may remain functional. If ever a proof were needed that nature is one, then this is it. We are all part of a single, many-splendoured creation, and are all related. To other warm-blooded mammals, we are very close kin. There is no avoiding this fact, and the distinctions which separate us from other mammals are relatively slight. These differences, which seem so considerable, can be reduced to little more than our remarkable linguistic ability and all that that has entailed during the last 100,000 years of our evolution.

Humankind evolved on this planet very recently in geological terms, and found the world almost in its present condition. Our own 5 million year history, like that of every other organic species, is one of adaptation to changing environments. During this process, however, we have also adapted to the many different existing environments, and today we occupy a wider variety of them than any other animal or plant species. An examination of the history of humankind’s environments can therefore give us direct insight into the actual process of human evolution. An understanding of our prehistoric environments can help us understand our own evolutionary adaptations: such knowledge alone can help us discover why we are what we are—why we are made the way we are, anatomically and behaviourally.

TERMS AND CONCEPTS

Ecology is the study of the relationship between a species and its total environment. This is a broad definition, but breadth of scope is the salient characteristic of the ecological approach. Human ecology, then, refers to the study of all those relationships between people and their environment (including such factors as climate or soil), and energy exchanges with other living species, including plants, animals, and other groups of people. If we take the broadest possible view, human ecology deals with the entire human species and its extraordinarily complex relationship with other organic and inorganic components of the world.

In practice those who have studied human beings from the ecological viewpoint have found it desirable to separate cultural ecology and social ecology as distinct sub-disciplines. Cultural ecology is the study of the way the culture of a human group is adapted to the natural resources of the environment, and to the existence of other human groups. Social ecologists study the way the social structure of a human group is a product of the group’s total environment. In this book we shall consider human ecology in a broader biological sense, but we shall also attempt to see how human culture and society have developed in response to the environment. We reco...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgement

- Preface

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 The Tropical Rain Forest: Our Distant Birthplace

- Chapter 3 The Tropical Savanna

- Chapter 4 The Temperate Forest

- Chapter 5 The Northern Grasslands and Coniferous Forest

- Chapter 6 The Tundra

- Chapter 7 Hunters and Gatherers

- Chapter 8 Pastoralism

- Chapter 9 Agriculture and Pollution

- Chapter 10 The City

- Chapter 11 The Human Ecosystem: Past, Present, and Future

- Suggestions for Further Reading

- Index