![]()

Part 1

Introductions

Limestone uplands like the Pennines plus a small region of igneous rocks with at least one extinct volcano. A precipitous and indented sea-coast.

W.H. Auden's conception of Eden, from The Dyer's Hand and Other Essays (1 968), quoted by permission of Faber and Faber

![]()

Chapter 1

In the cave of thunder

Sacred places in a northern landscape

The book begins with Sir Arthur Evans, one of the most famous archaeologists of the twentieth century. As a young man he excavated a Saami sacrificial site in Finland. This chapter discusses the ethnography of northern hunters and reindeer herders, and reviews what is known about such places today. It discusses their role in Saami perceptions of the world, and considers their implications for studies of the ancient landscape. In doing so, Chapter I introduces the idea of an archaeology of ‘natural places’. It concludes by describing the structure of the book and summarising the contents of the different sections.

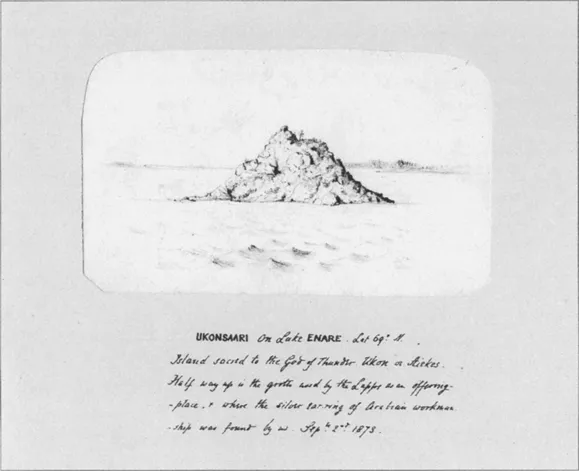

A traveller’s tale

In a lake in the north of Finland there is an island ‘shaped like a giant tortoise’ (Figure 1). It contains a sacrificial cave venerated by the local people. In 1873, during a storm that threatened his boat, an Oxford undergraduate made his way to the site. Perhaps it is not surprising that the island was sacred to the thunder god (Itkonen 1944: 3–4).

Figure 1 Arthur Evans’s sketch of Ukonsaari, Finland

Source: Reproduced by permission of the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford

On the steep flank of that island, Ukonsaari, was a shallow cave, although in fact it was little more than a small cleft in the rock face. It had supposedly been ‘used by the Lapps [Saami] as an offering-place’. Certainly, it was filled with bones. The roof of the cave was coated in soot, suggesting that it was still in use, and some of the burnt food that the visitor found was obviously of recent origin.

In a way that would be unthinkable today, he immediately decided to dig. Beneath the floor of the cave the bones were older, and he could identify the remains of reindeer and bear as well as other species. That was interesting in itself, but as he was preparing to leave, he came upon a deposit of charcoal, and in this he identified a metal ornament that he believed might date from the Bronze Age. Like the bones, it had apparently been burnt. Below this deposit there were human remains. He took the ornament, an ‘ear-ring’, home with him, together with a sample of the other relics.

We know what he found on Ukonsaari because he described the cave in a letter to his step-mother, who copied his account into a notebook which still survives. She was used to discoveries of this kind, for she was married to Sir John Evans, one of the founders of British archaeology. He was the first person to systematise what was known about prehistoric artefacts in this country and a collector of antiquities in his own right. His son had obviously inherited his interest in the past (Brown 1993: 11–19; Evans 1943: 174).

That visitor to the island was Arthur Evans, who was later to become one of the best-known archaeologists of his day, although the work for which he is most famous was to take place in the Mediterranean. In his early twenties, he was already adept at handling archaeological evidence. He noted that the cave on Ukonsaari was too small to have been inhabited, and in any case it was open to the elements. Its contents had an unusual character too, for there were no long bones among the animal remains, and fish bones were apparently absent even though fishing played a prominent role in the local economy. Still more striking, there were no antlers in the cave, although they had been deposited in large numbers on the rocks outside it. That was particularly significant, as he discovered that the local inhabitants used to arrange these antlers in a circle in honour of Ukon, the god of thunder, winds and lakes.

His interpretation was clear: no one could have lived in the cave because of its unusual topography. Its contents may not have been the remains of ordinary meals because of the ways in which the bones had been selected, and the ‘ear-ring’ was unlikely to have been lost by chance, especially as it seemed to have been placed in a fire. The collection of antlers found outside the cave recalled the offerings associated with Ukon. For Evans it was confirmation that this was a sacrificial site. How would we understand it today?

Saami sacred geography

There are two ways of introducing the archaeology of natural places. One is by extending the chronological and geographical framework of this chapter to take in other cases. The alternative (which I prefer) is to consider how much is really known about the phenomenon that Evans encountered on the island of Ukonsaari. I shall consider an example from his later career in Chapter 2.

The cave that Evans investigated in Finland can now be recognised as one of a series of sacrificial sites made by the native inhabitants of northern Scandinavia. Although some of the metal items found at these sites originated in distant parts of Europe (the silver ear-ring was from Russia), the main feature of these places was an extensive deposit of animal bones. The meat bones were inside the cave, whilst the antlers were found outside it. Saami metal deposits are not Bronze Age, as Evans believed, but date from a relatively short period between AD 1000 and 1350 (Zachrisson 1984). As his experience shows, the sites themselves were obviously used over a longer period.

In fact there seems little doubt that the Saami and neighbouring groups of hunters and reindeer herders were the indigenous inhabitants of northern Scandinavia. Prehistoric rock carvings show what seem to be the shamans’ drums for which the Saami were famous before the arrival of Christian missionaries. These carvings also illustrate the special importance of the bear, which is a notable feature of Saami ethnography (Helsgog 1987). In the same way, the Mesolithic burials at Olenii Ostrov in Karelia recall a number of features that are recorded among northern hunter gatherers, including the siting of the cemetery on an island. The artefacts from the graves recall the importance of elks and snakes in local systems of belief, and ancient rock carvings found in the same region conform to the symbolic system of the recent inhabitants of the area. Marek Zvelebil (1997) concludes that elements of a traditional cosmology lapsed at different times in different parts of northern Europe: they lasted into the mid-first millennium AD in Karelia, they were eliminated by Christian missionaries in northern Scandinavia in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries but they still survived until modern times in part of western Siberia.

This suggests that the deposition of metalwork on the island of Ukonsaari represented just one episode in a much longer history of ritual associated with natural places. This is certainly consistent with what is known today about sacred sites in the landscape.

The positions of more than 500 of these are now known (Manker 1957; Mulk 1994 and 1996). They are generally found at striking features of the natural terrain. Although some of these were inaccessible and could be reached only by those who knew where to find them, others were closely associated with the wider pattern of movement about the country. Some cult places served an entire community, whilst others were located along the routes by which people travelled at different times of the year. They might be visited by groups who followed the same paths or fished in the same lakes, but every family also had its sacred mountain where it provided offerings; sometimes the sacrificial site was located just below the summit (Rydving 1995). The main features to be treated in this way were (in descending order of frequency): hills and mountains, lakes, peninsulas, caves, islands, waterfalls and springs. A few offerings were also made in areas of pasture, but these places do not seem to have been distinguished by natural landmarks of the same kind. The sacrificial sites are generally known as siejddes. They are nearly all places that seem to be distinguished from the surrounding landscape by their striking topography. These features were not altered by the activities that took place there, and the rock formations that are such a conspicuous feature of siejddes were rarely modified by any form of structure, although some examples in the north of Scandinavia were enclosed by a low wall surmounted by brushwood, whilst others were ringed by a circle of antlers. In these cases, the main focus was sometimes a cairn (Manker 1957: 300–1; Vorren and Eriksen 1993).

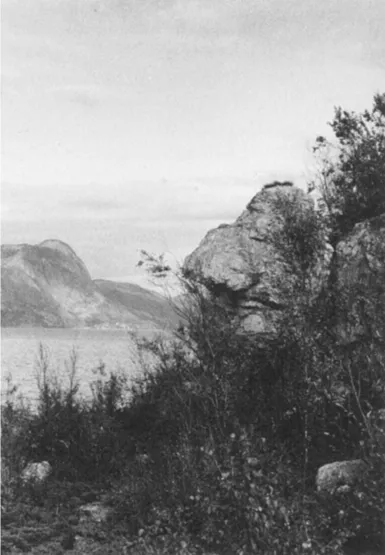

The siejddes are often characterised by rock formations that bear a certain resemblance to humans, animals or birds (Figure 2). These features were retained in their original forms and the shapes of these outcrops were never changed. [They] were not of monumental character, and thus did not express the idea that humans were in any way above nature’ (Schanche in Mulk 1994: 122). Manker makes a similar point when he says that ‘[the Lapps] let the gods choose their own shape’ (Manker 1957: 306). At the same time, it is clear that some of these stones have other obvious characteristics. They might be particularly massive or they could be an unusual colour. Some of the most distinctive were blocks that had been split open during cold weather to provide fissures or natural portals leading into the surface of the rock.

Figure 2 The natural setting of a Saami siejdde at Alta, Finmark, northern Norway

The sacrificial sites might be distinguished from the other parts of the landscape by their striking appearance, but they also included a variety of idols (Manker 1957). These were formed of two raw materials – stone and wood – both of which were very common in the natural world. Unworked stones were brought into service as idols, either because of their unusual colour or raw material or more often because their distinctive shapes resembled those of living beings. Some of these were introduced to the site, but it was extremely rare for them to be modified in any way.

There were also a number of wooden idols, although it is harder to decide how common these once were because so few have survived to the present day. The wooden idols were often carved out of the boles of trees, but even when this happened their forms were not altered materially. In fact it seems quite likely that these pieces were selected because their shapes already suggested the figures of deities.

Manker (1957) provides some interesting statistics on the character of both groups of idols. The commonest form was that of a human figure, and surviving images are more frequent in stone than in wood. Figures of animals are less often found. Virtually all of these were made of stone. In only two cases were naturally shaped pieces changed by carving. Like the siejddes, some of these attracted attention because of their shapes or colours. There are also cases where different materials were combined to imitate the separate parts of the body. For example, a deity could be depicted by a large, darkly coloured stone with a smaller, white stone placed on top. Some of the stone ‘figures’ were interpreted as the sons or servants of the thunder god or even as incarnations of the divine master of the animals.

As we have seen, the wooden idols were more complex and at least some of them had been carved. In this case there is an added complication, for living trees also seem to have been worshipped, and a number of these may have been embellished in the same way. It was common for a wooden idol to be formed from the base of the trunk. This seems to have had a special significance, as the idol was normally made by turning the raw material over, so that the roots were uppermost (Manker 1957). Such images include the thunder god who was worshipped at Ukonsaari, and Varaldenolmmái who ensured the fertility of the reindeer and of the pastures where they fed.

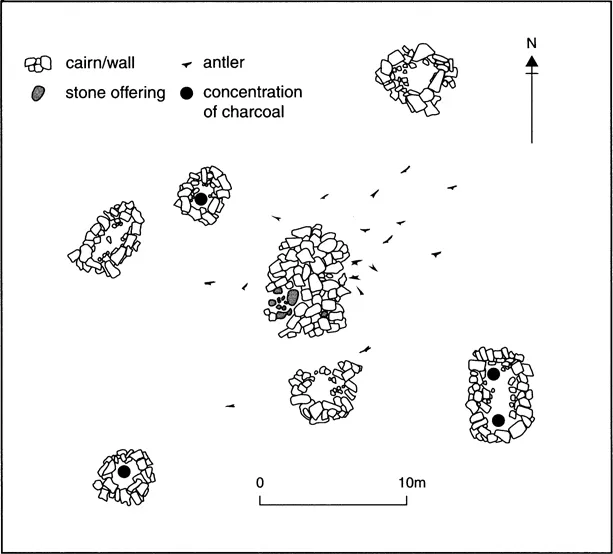

The sacrifices themselves were intimately connected with the exploitation of the local landscape (Figure 3). Thus there were siejddes that were associated with the sacrifice of animals by hunters and herders, and others that were used for offerings of fish (Rydving 1995: 20). The animal sacrifices were generally shared with the gods. The people visiting the sacred sites consumed the meat, frequently reindeer, and left the bones, skins and antlers behind for the gods, who were capable of putting new flesh on the remains. Like the idols associated with these sites, the sacrificial rock was smeared with blood and grease, as well as fat, milk and sometimes cheese. On some sites the bones of a single reindeer were buried under a cairn beside a large boulder, but with the antlers left exposed. A similar importance attached to the killing and eating of the bear. None of its bones could be broken or discarded. Instead they were carefully collected and stored until they were eventually buried. It was a common practice in the Arctic for the bones of a sacrificed animal to be restored to their anatomical order when the remains were committed to the ground (Manker 1957).

Figure 3 A Saami sacrificial as depicted by Johannes Schefferus in 1673

The sacrifices were dedicated to natural forces, important in the life of the Saami, such as thunder, the winds, waters and the sun. Particular gods were associated with particular kinds of sacrifice, and to some extent the same applies to offerings that were made for different purposes. Thus black animals were sacrificed to the forces of death, and white reindeer could be offered to the sun god. Horses were sometimes sacrificed when someone was expected to die, and the thunder god might receive an uncastrated reindeer (Mulk 1996; Rydving 1995).

Decisions were reached by consulting the shamans’ drums (Rydving 1995). The sound of the drum told the shaman where food could be located and allowed him to see into the past and future. Bone or brass pointers attached to the surface of the drum also provided directions. The drum offered a variety of practical information, but in some cases it instructed the Saami about the proper form of sacrifice. At times it was necessary to embark on long journeys to obtain the appropriate victims, including domesticated animals such as cattle, horses, sheep and goats, which were brought from areas a considerable distance away (Mulk 1996). The sacrificial sites were the domain of the ancestors, and all were given names. Different locations were associated with different divinities. One group of mountains might be linked with the spirits of the ancestors, whilst another might be the province of the mother goddess or of the god of thunder. Women’s ancestral spirits were also associated with certain lakes.

Manker’s study combined the documentary history of the Saami with an exhaustive catalogue of finds from the votive deposits themselves (Figure 4). This shows that the bones and antlers of reindeer were deposited in well over 100 different cases (Manker 1957). Domesticated animals were sacrificed at about a quarter of the sites, and bears were even less common. There was also direct evidence for the sacrifice of birds and fish.

Figure 4 Detailed plan of the Saami sacrificial site at Grythaugen, Varanger, northern Norway

Source: Information from Vorren and Eriksen 1993

In addition to these remains, there are numerous finds of artefacts. These include metalwork and pieces of quartz, flint and glass. Some types of metal were thought to carry special powers. Brass was sacred: it was used for the pointers on the shamans’ drums and is also associated with bears’ graves. Silver, which occurs more frequently in the sacrificial deposits, is never found in these burials. Many of the artefacts were imported from distant parts of north-west Europe; this is particularly true in the case of coins. Objects made of pewter, however, seem to have been locally produced. One deposit of unfinished artefacts was found in a Swedish lake. Although this has been explained in mundane terms, the fact that similar locations were being used for votive deposits suggests that metal production could also have been undertaken in special places and may have been attended by rituals (Zachrisson 1984: Chapter 3). It seems as if some of the artefacts were used to decorate organic objects, including wooden figures, antlers and drums. Among the other items found in votive deposits are iron arrowheads of exceptional quality (Mulk 1996). These may have been sacrificed at the conclusion of a particularly successful hunt. I shall return to the significance of some of the metal finds in Chapter 4.

Why were these sacrifices undertaken? There seem to have been a number of reasons, but all of them were closely bound up with the daily lives of the Saami. One of the main purposes of sacrifice was to ensure a dependable food supply. Thus offerings were made to the divine masters of the animals and to the supernatural rulers of different r...