Introduction: Providing Meaning to Theory

Reverend Donne’s well-known passage expresses this book’s theme, social systems theory. General systems theory (GST), which includes the narrower field of social systems, is a cross-disciplinary body of scientific thought that emerged during the mid-twentieth century.

This chapter will introduce the basics of the social systems approach to understanding human behavior. We will provide a brief overview of the scientific context that gave rise to systemic thinking and the particular version known as social system. We will define and discuss basic concepts, some of which include terms that may be new to you, such as holon.

We will also discuss familiar terms, such as energy and organization, but some of these terms will have new, important meanings.

The social system model that we present in these first two chapters provides organizing principles for this book. This model enables the reader to recognize similar or identical ideas (isomorphs) emerging from different scientific and philosophical ancestries and provides a scheme for classifying and ordering such related ideas. Most importantly, it provides a means to understand human behavior better and may point to new directions for professional practice (see Addendum to Chapter 2).

One systems theorist says:

For decades, and even perhaps for 100 years, social science has been trying to describe, or hit, a moving target—nonlinear behavior. It has been scoffed at as “soft science,” but this may no longer be the case. Potentially, these theories of nonlinear-ity indicate that [it] is more difficult to study nonlinear phenomena, tougher to pin things down. Entirely possible is the notion that social science has been doing the most difficult work in science. (Bütz, 1997:xviii)

The advent of computers has allowed testing of nonlinear hypotheses (e.g., of fractal geometry and so-called “fuzzy logic”). This has presented exciting (and frequently unanticipated) insights into commonalities among the natural (or “hard”) sciences and social (or “soft”) sciences.

At times, we will describe it as the social systems perspective, a philosophical viewpoint on the relationship of persons with their social environment. Occasionally, we will also refer to it as the social systems model, meaning that it is a hypothesis to be tested, primarily through its application to professional practice and praxis in various professions and disciplines. Since “person-in-environment” (or PIE, as it is abbreviated) is a central motif of social work and of other human services, the systems metaphor is particularly well suited to social work practice. Gordon Hearn first stated this connection:

... if the general systems approach could be used to order knowledge about the entities with which we work, perhaps it could also be used as the means of developing a fundamental conception of the social work process itself. (Hearn, 1969:2)

This conception is useful to other professions as well, for example, psychology, nursing, education, communication, and medicine. A generation ago, Auger stated that a systems approach enabled the nurse

to evaluate the status of the person who is ill and the significance of changes that may or may not have occurred in patterns of behavior. This content will help the student to develop a broader concept of the relationship between health and illness, the wide variations of “normal” behavior, and changes that may occur as a consequence of illness and/or hospitalization. (Auger, 1976:x)

At the same time, Monge argued that a systems perspective provides the best theoretical basis for the study of human communication: “That perspective which incorporates the others is, until at least more information is available, the one best suited to guide us in our quest for knowledge about human communication” (1977:29).

A. Systems and Systemic Thinking

In most dictionaries the first meaning of system is “a set of things or parts forming a whole,” “a complex unity formed of many often diverse parts subject to a common plan or serving a common purpose,” or something similar. Systems thinking then means using the mind to recognize pattern, conceive unity, and form some coherent wholeness—to seek to complete the picture (which Ion Georgiou [2007] says is inherent and a driving compulsion in human consciousness). That which is called system comprises elements cohering in some intelligible way, that is, capable of being understood.

As humankind seeks to find order and the quality of wholeness amid disorder and meaning, thought is patterned and imposed on the world as experienced by the observer (see the discussion of this point in the Addendum to Chapter 2). This point is thoroughly and precisely presented by Georgiou in his book, Thinking Through Systems Thinking (2007).

Systems thinking includes those ways of thinking that seek to understand unity and connectedness of all life. A recurrent phrase that conveys this quality of coherence is, “hang together.” Here are two uses of that phrase from quite different sources (emphases added):

[H]e who wants to have right without wrong,

Order without disorder,

Does not understand the principles

of heaven and earth

He does not know how

They hang together.

—Chuang Tzu, poet-philosopher of Taoism

The doctrine that everything in the universe hangs together . runs as a leitmotif through the teachings of Taoism and Buddhism, the neo-Platonists, and the philosophers of the early Renaissance.

—Arthur Koestler, philosopher (1979:265)

Comprehension of the part/whole nature of life is the central tenet of systems thinking. From this flow the propositions of our social systems approach.

I. Essence and Ancestry: The Atomistic/Holistic Continuum

A social system is a special order of system within general systems. It is distinct from atomic, molecular, or galactic systems in that it is composed of persons or groups of persons who interact and mutually influence each other’s behavior.

[A] social system is a model of a social organization that possesses a distinctive total unity beyond its component parts, that is distinguished from its environment by a clearly defined boundary, and whose subunits are at least partially interrelated within relatively stable patterns of social order. ... [A] social system is a bounded set of interrelated activities that together constitute a single entity. (Olsen, [1968] 1978:228-229)

Social systems exist at all “levels”: persons, families, organizations, communities, societies, and cultures. It is important, both analytically and ideologically, to specify what should be seen as the “basic unit” of social systems. In order to explain adequately what we consider the “basic unit” of social systems, we must step back and review the theoretical positions that have emerged.

Within sociology there historically have been opposite positions on the designation of the primary social unit: “macro” vs. “micro,” or whole vs. part. Macrofunctionalists, such as Talcott Parsons, tended to view the society as the primary focus and therefore to view the behavior of smaller human systems and their components as being determined by the society’s needs and goals, i.e., the whole determines the actions of its parts. Simply put, people are determined by society. This is a wholistic viewpoint.

At the opposite pole were social behaviorists and social interactionists, such as Max Weber and G. H. Mead. They began with the smallest unit of the system, the behavior of the individual person. In this view, the acts of the individual persons tend to cluster into patterns; therefore the social system is constructed out of these patterns; i.e., the whole is the sum of its parts. Simply put, persons determine the society. This is an atomistic viewpoint. The wholistic view implied “downward” causality, while the atomistic view implied “upward” causality.

These two positions are important and powerful when applied to the task of deciding how to (or whether to) intervene in human behavior, as well as to explaining how change is achieved in the realm of human endeavor. Within social work education and practice, this duality has emerged as the historical distinction between casework and community organization, or as “individual change vs. social change.” The social change emphasis is grounded in the macrofunctionalist view that behavior is primarily determined by the larger social systems: macro-systems such as society, community, or organization. Emphasis on clinical or individual change is based on the belief that society is constructed from the behavior of the person. This duality is inherent in other social/behavioral disciplines, most explicitly in the paradigm of “nature vs. nurture.” This phenomenon of polarity will be a recurrent theme throughout the remainder of this book. Most significantly, it is this duality and its historical tension that gave rise to the necessity for an integrative tool such as the social systems approach.

B. Holon

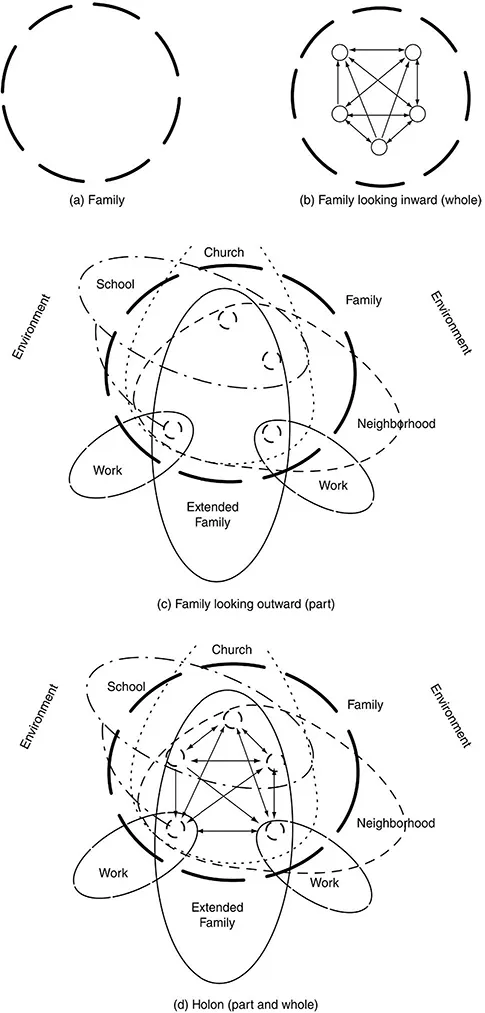

We hold that both polar positions must be considered when examining human affairs. There must be attention to both the whole and the part. Our point of view is that each social entity, whether large or small, complex or simple, is a holon, a term we borrow from Arthur Koestler (who borrowed, in turn, from the Greek language) to express the idea that each entity is simultaneously a part and a whole. A social unit is made up of parts to which it is the whole, the suprasystem, and at the same time it is part of some larger whole of which it is a component or subsystem. Like the Roman god Janus, a holon faces two directions at once—inward toward its own parts, and outward to the system of which it is a part. What is central is that any system is by definition both part and whole (see Figure 1.1).

The individual person constitutes the apex of the hierarchy of organisms and, at the same time, is the lowest unit of the social hierarchy (Figure 8.1 conveys this idea). The concept of holon is particularly useful; it epitomizes a consistent theme in this book: Any system is by definition both part and whole. No single system is determinant, nor is system behavior determined at only one level, whether part or whole.

The idea of holon as used in this book extends Koestler’s proposition of whole/part relationships to include certain corollaries:

The systems approach requires the specification of a focal system, which is the system chosen to receive primary attention. Another way of saying this: the choice of focal system identifies the perspective from which the observer views, and analyzes, the system and its environment (see perspectivism in Glossary). In other words, “from where I sit. ...”

The idea of holon then requires the observer to pay attention to both the components (subsystems) of that focal system and the suprasystem of which the focal system is a part (or the significant environment to which the focal system is related), in order to fully understand it.

In Figure 1 (parts a-d), diagrams of a family are useful to explain the concept of a focal system. If the family is viewed as a holon, attention must simultaneously be given to both the family’s members and to its significant environment such as schools, community, work organizations, other families, and neighborhood. To focus only on the interactions among family members (family as suprasystem) ignores the family’s interactions with larger systems (family as subsystem).

Social systems theory may be described as “contextual,” “interactional,” or perspectivistic. The latter term connotes that causation, or the significance of an event, is relative to the focus one has at the time of assessment; that the interpretation one places on events depends upon where and who one is and the perspective one has upon the focal system. As an example, recall in your own experience when you witnessed a situation and someone else who witnessed the same event described it very differently (the classic film Rashomon portrays the same events as seen by four different people; the more recent film Vantage Point (2008) employs a similar technique). It is the same in larger social/historical contexts: as events are viewed by other observers or at other times, meanings are often likely to change. Social systems theory is “holonistic,” requiring

specification of the focal system and its boundaries;

specification of the units or components that constitute that holon;

specification of the significant environmental systems; and

specification of one’s own position relative to the focal system.

Figure 1.1

Diagrams of a family system, (a) Family, (b) Family as a whole: looking inward, (c) Family as a part: looking outward, (d) Family as holon (part and whole).

This is the process that Georgiou (2007) calls “intuiting” the “identity” of the system. It is also what some systems theorists take as the “emergence” of the system; that is, when an observer sees systemic characteristics, the system “emerges” (see Addendum to Chapter 2). This process can be called mapping. One example is the use of “ecomaps” in family systems approaches to understanding and helping families.

Components and environment find their meaning in their effects on the focal system and, conversely, the focal system finds meaning in its effect on its component parts and its environment. To define a family and its components, one asks, e.g., is the father/husband present or absent? are grandparents or other extended family members present? what is their significant environment, a middle-class suburb, or a Brazilian favela? Who is the observer, and what is her/his role: Is she a “member of the wedding,” caseworker, or police officer? Is he the family’s therapist, patient’s nurse, or community’s organizer? Such a persp...