- 382 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Efforts at coordination between nations are at the heart of the challenges of globalization. Despite steadily growing interdependencies, individual nations still have specific interests that present obstacles to globalization. While some challenges inspired by the need to coordinate are viewed as inevitable by many, they are less optimistic about prospects for success. Jan-Erik Lane argues that one should focus objectively upon the possibility of failures.Lane analyzes four kinds of challenges to interdependency, all of which are growing in geopolitical relevance. First, countries need to diminish their dependency on fossil fuel and shift to a reliable supply of energy, because fossil fuels are diminishing. Second, environmental degradation must be addressed, because it is accelerating under the strain of earth's population. Lane advocates an ecological footprint approach. Third, a single global market economy and its complexities must be addressed, as national economies are increasingly opened. Finally, as traditional state sovereignty weakens, foreign military intervention in both international and intra-state conflicts increases.Governments are attempting to address these interdependencies, or reply to the challenges they pose, mainly through international organizations and regionalism. These efforts are discussed at length. In addition, problems with international law are reviewed, as Lane warns against the utopian hopes of global constitutionalism. Globalization also examines the potential consequences of failing to address the need for coordination in efforts to address shared global challenges.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Energy and Ecology

Introduction

Globalization theory must pay particular attention to the political implications of global energy and ecology policies. When making energy policies, governments should be conscious of the environmental implications of alternative policies. Just as energy policymaking has started to take global scenarios into account, global ecological considerations have become relevant for each and every country in the world. When considering alternative options, governments must know the environmental consequences of each. The politics of energy and ecology are one of the main themes in the debate between so-called “cornucopians” and “ecologists.”

The massive amounts of usable of fossil fuels made available throughout the twentieth century offered people access to cheap and efficient energy resources, allowing for a sharp increase in affluence, at least for some countries. However, this extreme reliance upon fossil fuels has come with a heavy price as mankind faces the threat of global climate change in the twenty-first century due to the accumulation of CO2-equivalent emissions in the atmosphere. The greenhouse effect, although contested among a few scientists and economists, has become a global policy issue. The stakes involved have surfaced in global meetings among the governments of the states of the world, such as during the Copenhagen Climate Summit of 2010.

The aim of this chapter is to explore the connection between energy and environment by means of the energy-environment conundrum. In order to create an economic output, as measured by GDP, energy has to be used which, in turn, results in CO2 emissions. The global conversion of energy into output and accompanying CO2 emissions must be examined across time and geography via a focus upon the link between GDP and CO2 emissions. The energy-environment conundrum results in state interdependencies, wherein no government can go it alone due to the fundamental PD game nature of the country interaction. But environmental coordination is difficult to accomplish, especially concerning the CO2-equivalent emissions that are closely linked with country affluence or GDP.

Global Peal Oil?

Energy consumption continues to increase. At the same time, cheap energy sources are depleted at an incredible pace. Thus, the energy challenge arises: how to shift from nonrenewable energy sources to renewable ones. The consumption of energy is at the core of economic development as well as at the environmental predicament that is climate change. The importance of energy production and consumption cannot be exaggerated. There are bound to be energy shortages in the twenty-first century and accompanying increases in the price of energy.

When energy is approached from the perspective of physics, then the situation for mankind does not appear to be alarming. After all, thermodynamics teaches that energy is indestructible. However, looking at energy from the perspective of the social systems of mankind, an entirely different outlook appears. What counts for mankind is available or usable energy, not the immense total energy in the entire universe.

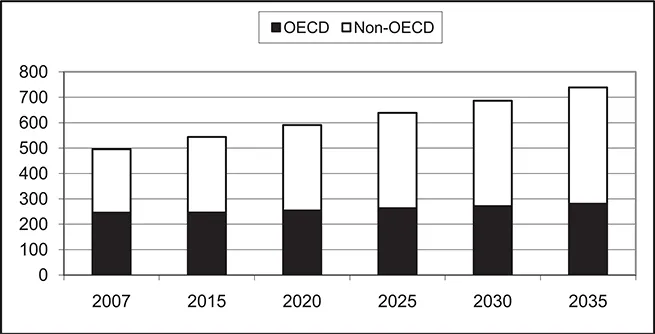

It is true that global energy consumption has increased sharply since 1970. It is now predicted that it will almost double in the coming twenty years (see figure 1.1). One observes that the emerging economies outside of the OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) club of states are predicted to overtake the OECD countries in energy consumption.

It must be asked how so much more energy could be produced in 2035 than now given the planet’s already incredible levels of energy stress. Despite the fact that energy production will double in the future, the problem becomes the level of access to new sources of energy during this century. Energy shortages will hamper economic development, and considerably higher energy prices may turn these predictions wrong as well as make some of the UN Millennium objectives unachievable, i.e. too costly. The chief difficulty is that the available oil reserves are being depleted quickly, not enough new ones are found, and the new ones that are found are increasingly costly to exploit. The energy-environment conundrum implies that the depletion of oil reserves is compensated for by increasing use of coal, thereby fuelling global warming.

Figure 1.1 World marketed energy consumption.

Source: US Energy Information Administration (EIA).

Most energy is derived from fossil fuels: oil, natural gas, and coal. Together with nuclear energy, these constitute the nonrenewable sources of energy that mankind consumes at alarming speed. The fossil fuels took millions of years to build up on planet Earth, but mankind is depleting them in a period of only two centuries. On average, about ninety percent of total energy comes from nonrenewable sources (a figure that varies much from one country to another) (EIA).

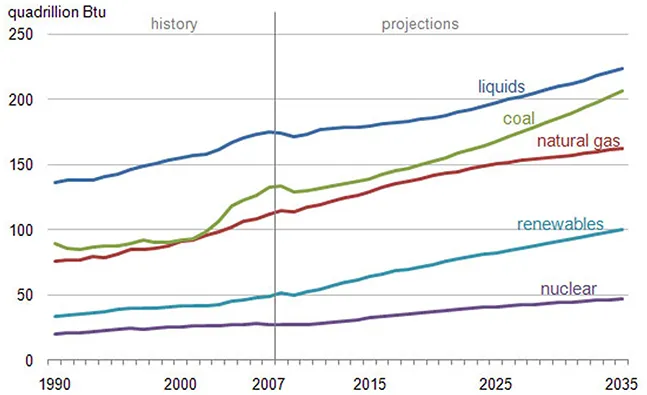

The standard prediction for energy use by type of energy source appears in figure 1.2. Although the stylized scenario comprises a considerable increase in energy from renewable sources, figure 1.2 still projects that the fossil fuels will be the dominating source in 2035, with oil as the largest contributor. The discovery of shale oil and gas has changed the situation, delaying the period of peak oil has been by some ten years.

One may question these predictions concerning the mix of energy sources. The crux of the matter is the occurrence in time of the Hubbert peak for global oil production. Although Hubbert was not correct in his prediction that global oil production would peak in 2000, his analysis of the American industry was right as he predicted the peak year would be 1971. After oil production peaks, output falls quickly, according to the Hubbert peak concept.

It is rather impossible to make a daring projection suggesting that today is when the global Hubbert peak for oil is occurring. It would only hold, if true, for conventional petrol because the advent of massive use of shale oil deposits has changed the supply of energy derived from fossil fuels. The production of energy from shale oil is changing the scene in the global energy market, especially for the US. However, exploiting shale oil deposits has severe environmental consequences, thereby fueling the political controversy of energy and ecology.

Figure 1.2 World marketed energy use by fuel type.

Source: US Energy Information Administration (EIA).

Several oil-producing countries, such as the UK and Norway, have gone beyond their production peaks. Russia will face its peak for conventional oil before 2020 (EIA). The idea of peak oil is based upon two components. On the one hand, existing wells are rapidly depleted due to the enormous thirst for petrol. On the other hand, it becomes increasingly more difficult and expensive to find new wells in more and more remote areas of the globe. What could derail all projections is that the oil reserves of some countries, like Saudi Arabia and Venezuela, have been exaggerated or political instability will prevent full access to the oil reserves in countries like Iraq and Kazakhstan.

The CO2 Emissions Problem

The future energy scenario not only includes the so-called Hubbert peaks for global oil and natural gas production, but it is also much complicated by the controversy over the ecological consequences of the heavy reliance upon nonrenewable energy sources. The so-called cornucopians maintain that the price mechanism offers a solution to the energy-environment conundrum, whereas the entrenched ecologists rebut this position, arguing that global energy production must be given a new direction towards renewable energy sources that do not harm the environment.

In the global discussion of CO2-equivalent emissions, much attention has been given over the last decade to introducing policies that halt the rapid growth in these emissions. Global environmental coordination is, however, very difficult to achieve given the nature of this gigantic PD game in combination with weak institutions for policymaking and implementation. In UN environmental coordination, one tends to neglect the fundamental fact that emissions are closely linked with economic development, which sets up the dilemma of the energy-environment conundrum. And few people wish to undo economic growth. The only way to stabilize CO2 emissions is to focus upon the conversion factor linking energy to output to pollution. Emissions remain far too high, making global climate change almost certain.

In the ever-more-intensive global debate on CO2 emissions, the consequences and possible policy responses of global environmental coordination, one basic fact has not been given enough attention: the connection between GDP and CO2-equivalent emissions of various kinds. This connection between global economic output and pollution is crucial for understanding the climate change debate and its policy options concerning the trade-off between affluence and ecology. In order to create an economic output, as measured by GDP, energy has to be used, and that inevitably results in CO2 emissions. The conversion of energy into output and CO2 emissions may be studied over time as well as over space by focusing on the link between GDP and CO2 emissions.

Three Types of Pollutions

Among the cornucopians, it is believed that affluence reduces pollution. This was the classical policy stance of Simon (2003) and Wildavsky (1997) that rejected the relevance of environmental policies that reduce CO2 emissions. However, they fail to distinguish between three very different forms of pollution when it comes to the effects of rising affluence (i.e., GDP). The visible and invisible pollution must be separated, as must direct and indirect pollution. Thus, we have three major kinds of pollution that result in reduction of species and the threat to endangered animals:

- Littering or petty pollution: occurs massively in poor Third World countries like India, Myanmar or Fiji

- Toxic waste, heavy metals and sewage: found on a large scale in the emerging economies, where high levels of growth are combined with weak environmental protections

- CO2 pollution: takes place in industrial and post-industrial economies that require massive inputs of energy in various forms such as transportation, heating, cooling, etc.

Whereas rising affluence would tend to result in less littering and toxic waste, especially if the additional resources resulting from economic growth are put towards public policies or cleanup efforts, it is definitely not the case that economic development or quick economic growth decreases CO2 emissions, as we shall see below.

It is absolutely essential to separate these different forms of pollution. Dinda (2004) has shown in several articles that the relationship between per capita income and different pollutants is complex, varying between different sets of countries depending upon...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- copyright

- contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part Challenge One The Energy-Environment Conundrum

- 1 Energy and Ecology

- 2 Environmental Deficits

- 3 Climate Change Is Unavoidable

- Part Challenge Two Managing One Global Market Economy

- 4 The Real Economy and the Financial Economy

- 5 Global Economic Coordination Mechanisms

- 6 Global Imbalance

- Part Challenge Three Managing Violent Political Conflicts

- 7 Political Interdependencies

- 8 A New Pattern of Global Conflicts

- Part Challenge Four Regional Coordination: How Effective Is It?

- 9 Governance of Common Pools

- 10 Regional Organization: No Ideal-Type Model

- Part Challenge Five Good Governance

- 11 Global Institutionality and Normativity

- 12 Mankind and Global Rule of Law

- Conclusions

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Globalization by Jan-Erik Lane in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Globalisation. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.