- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Social Work Constructivist Research

About this book

This is the first textbook to offer a clear, concise articulation of the dimensions of constructivism relevant to social work practice and research. Professor Rodwell recognizes the need to systematize a process of knowledge building and presents specific techniques to accomplish that while maintaining an interpretative stance with the focus on meaning. Social work students will see that their basic way of engaging clients in an assessment and problem-solving process is very much in keeping with constructivist research practice. In addition to delineating the philosophical assumptions of constructivism, this very practical text is geared to classroom use, with chapters on research design, rigor, data collection, data analysis, research oversight, and presentation of results. Social Work Constructivist Research is divided into four sections that, together, should give the reader the intellectual and practical background necessary to understand and undertake rigorous constructivist inquiry. The structure of this textbook is intended to provide the reader with sufficient information to competently confront all the design, implementation, and reporting elements of a constructivist inquiry process. At the completion of all sections, readers will know how the assumptions of constructivism differ from mainstream research primarily characterized by positivism or post-positivism. Readers will know how rigor expectations for research methods derived from different assumptions also differ. They will know how to: determine the feasibility of undertaking a constructivist inquiry, when, and where it is possible; manage an emergent design; and establish the trustworthiness and authenticity dimensions of a rigorous research effort. For those interested in constructivist research and its relevancy to social work, this book will prove to be a necessary resource.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Section II

Doing Constructivist Research

Section II further develops the framework for constructivist inquiry by providing the design and development details necessary to create a rigorous constructivist process with the possibility of a meaningful constructivist product. Chapter 3 introduces the general form and flow of a constructivist research project. Details about constructivist research methods logically linked to constructivist assumptions can be found here. The elements of a constructivist inquiry, including the phases of a constructivist process, are introduced to clarify what constitutes constructivist methods. All dimensions discussed are necessary for implementation, if the research is to be called constructivist.

Chapter 4 explores the interventive aspects of constructivism. Praxis and research as an intervention are discussed to further clarify the affinity between social work practice and constructivist inquiry. The major messages in this chapter concern the hermeneutic circle and achieving a productive dialectic. Details are provided about how to maintain a quality hermeneutic circle, including the responsibilities of the inquirer.

The remainder of this section covers the constructivist methods or what is necessary to really “do” constructivism. Chapter 5 develops the various dimensions of constructivist research rigor including trustworthiness and authenticity. From this chapter, readers will have the basic information necessary to establish all aspects of a quality constructivist process and product with defensible constructivist rigor.

Chapters 6 and 7 lay out the data collection and data analysis aspects of constructivist inquiry. Though much information in these chapters will at first appear familiar to those schooled in traditional qualitative data collection and analysis, the required emergent nature and grounded theory development of constructivism will be emphasized in order to create the alternative, interpretive nature of this type of inquiry. This section ends with the most radical difference in constructivist inquiry, negotiating the results of data analysis with the participants in the inquiry, who are seen to both own the data and have a stake in the framing of the results. Continued linkage to the values and empowerment tradition in social work will be apparent.

Again, the reader is encouraged to participate actively in the learning process by completing the discussion questions and exercises at the end of each chapter. The exercises in this section are essential to understanding how to conduct constructivist data collection and data analysis. Completion of the exercises is guaranteed to save much time for the researcher who is interested in engaging in a full constructivist inquiry. Each activity has been tested by students who say that, because many of the usual mistakes in implementation will be made during the exercises, those mistakes can be avoided when the actual work of constructivism is undertaken.

Chapter 3

Designing Constructivist Research

Chapter Contents in Brief

- Form of constructivist inquiry

- Methods of constructivist inquiry used in the entry condition, the inquiry process, and the inquiry product

- Phases of constructivist inquiry

- Planning data sources, data collection, and inquiry logistics

The central assumptions in constructivism regarding the context-dependent nature of reality, multiple perspectives, many ways of knowing, and the impossibility of generalizable knowledge suggest that research design in constructivist research involves giving the most possible structure to an emerging process and product that is actually without predictable structure. Though the exact details of any constructivist inquiry cannot be envisioned in advance, certain aspects can be foreshadowed. When engaging in constructivist research design, the researcher will be the architect of a process that Guba and Lincoln (1989, pp. 186–187) have described as the “flow” of a constructivist inquiry. This flow begins with what was discussed in the last chapter: determining the fit, focus, and feasibility. It also includes organizing the inquirer for undertaking this activity by being certain that the inquirer or the inquiry team is trained in constructivist principles and methodology. One cannot expect to conduct an effective constructivist inquiry without training or practice beforehand.

Next, the stakeholders, those with a stake in the phenomena under investigation in the context of the investigation, should be identified and the effort begun through a hermeneutic process to develop within-group joint constructions. This occurs when data are shared between and within the relevant stakeholding groups. Greater sophistication is then achieved by enlarging joint stakeholder constructions through acquisition of new information to expand the depth of meaning, to fill gaps, or to perform additional checks of credibility.

Consensus emerges as claims, concerns, and issues are identified and resolved. Those that remain unresolved are prioritized and opened to further information collection for added sophistication. Those claims, concerns, and issues that remain unresolved are then negotiated among the stakeholders, including the inquirer, in order to come to resolution. Those constructions where resolution has been achieved become part of the final case report. Those elements where resolution is not possible are part of a minority report and may also become a part of “recycling” (Guba 8c Lincoln, 1989, p. 226). Recycling occurs when the results of the inquiry are returned to the context for further consideration. Here the inquiry comes full circle for a final effort in co-construction.

Actually, constructivist processes are, by their nature, so emergent that the flow is never-ending. The inquiry will raise more questions than it answers. The unresolved claims, concerns, and interests remain a part of the context. This means that the results of the inquiry process and product will continue to reverberate in unexpected and uncontrollable ways even after the inquirer has left the process.

A variety of interactive qualitative methods must be utilized during the flow of the emerging constructivist inquiry. The implications of constructivist assumptions are seen in the research design, data collection and analysis, and reporting, and in the rigor expectations associated with a quality constructivist process and product. This chapter will discuss the range of what constitutes constructivist methods for use in planning and implementing a constructivist inquiry.

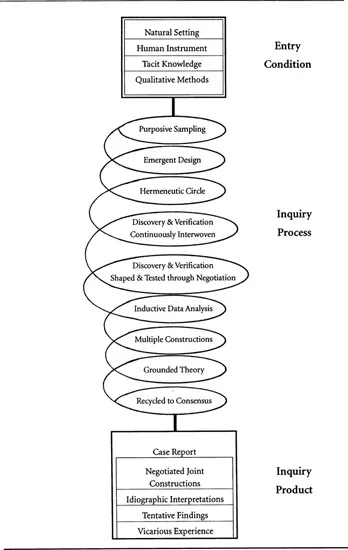

Though each research process is unique with respect to the time, place, and data sources, a constructivist inquiry can be discussed in terms of its form, process, and product. The major methods that constitute constructivist methodology are seen in the details of these three dimensions. Figure 3–1 depicts the form of the inquiry. Note that constructivist inquiry form is not as static as it is depicted on the written page. Instead, it is interactive, going back and forth in a constant process of data collection and verification, of theory construction and verification. The inquiry and the knowledge creation are on a course of continuous shaping involving discovery and validation. The process is always interwoven from the

Figure 3–1 The Form of a Constructivist Inquiry

entry into the inquiry, through the co-construction of meaning, to the construction and negotiation of an inquiry product. Though the form appears linear, it is important to think of it in terms of multiple dimensions with many embedded circles spiraling toward a visceral conclusion. Note that in Figure 3–1 the only aspect that appears to have solid form is that of the entry condition. Therefore, if a natural setting cannot be investigated by a human instrument, combining tacit knowledge with qualitative methods of data collection, then a constructivist inquiry is not possible.

Constructivist Methods

In order to assure the constructivist form, certain methodological considerations are necessary. The following section will cover these methods. Note also that they constitute important methodological consequences of constructivist assumptions. Table 3–1 contains all methodological elements for both the constructivist process and the product.

Table 3–1 The Constructivist Research Design

| Aspect of Inquiry | Methodological Element |

| | |

| Entry | Natural setting |

| Prior knowledge | |

| Research design | Emergent design |

| Problem-determined boundaries | |

| Purposive sampling | |

| Data collection | Qualitative methods |

| Human instrument | |

| Tacit knowledge | |

| Data analysis | Inductive data analysis |

| Grounded theory | |

| Rigor | Trustworthiness |

| Authenticity | |

| Inquiry product | Negotiated results |

| Idiographic interpretations | |

| Tentative applications | |

| Case study reporting | |

Each is as important as the others. If all aspects cannot be undertaken, interesting research may result, but it will not be an inquiry process that can be called constructivist.

Entry

To enter a constructivist inquiry, the research must be mounted in the natural setting of the phenomenon or problem under investigation. Notice that the elements necessary at entry into the research process are related to the context embedded nature of constructed realities. The flexibility and adaptability necessary at the beginning stages of an inquiry will be ensured if they are present.

A natural setting is elemental to constructivism because reality cannot be understood in isolation of its context; reality cannot be separated into fragments or parts. The wholeness of what is real is only understood when attention is given to the factors that shape the environment, the patterns of influence that exist, the values that are accepted, and so forth. All of these elements shape the webs of relationships in which understanding is constructed. The researcher must be interacting with the setting and with its inhabitants in order to achieve the fullest possible understanding of them, their actions, and their constructions. Through these interactions, meaningful reconstructions will become the products of the process.

Some prior knowledge of the subject under investigation is necessary in order to determine what constitutes the natural setting for the fore-shadowed questions (McMillan & Schumacher, 1993). Foreshadowed questions are those questions that guide beginning data collection. This knowledge comes from a thorough review of the literature, determining the focus of the inquiry (pure research, evaluation, or policy analysis), and performing what Spradley (1979) calls prior ethnography. Information about context, its “meets and bounds,” human and political structure, values and culture comes from “hanging out” in the environment in a community site survey mode used in ethnographic community assessment (Lofland & Lofland, 1995). This same type of “hanging out” is used to identify the limits of a service unit, an agency, a neighborhood, or a community, all of which might be the natural setting of a social work research project.

Once prior knowledge can be combined with information about the natural setting of the phenomena under investigation, the other aspects of the inquiry can be elaborated. Constructivist design, data collection, data analysis, rigor, and the inquiry product are also keenly imbedded in and can be derived from constructivist assumptions.

Research Design

The research process develops according to an emergent design, that comes from the experience rather than being totally developed a priori. No researcher will know enough beforehand about the context and the multiple realities that will emerge to adequately devise a design. Exposure to the special circumstances and the unpredictable interactions will determine what is interesting and important to be understood, and who should participate in the co-construction. All of the actors, values, and peculiarities of the environment are allowed to shape the character of the research design and process. Each inquiry process will be different because it will be created by the individuals involved (Burrell 8c Morgan, 1979).

Problem-determined boundaries are created by the participants to limit and shape the focus of the inquiry. The realities and values of all participants, including the inquirer, limit or expand the margins of what the real question will be and who should participate in the construction of the answer. The focus of the inquiry emerges with the design and is shaped by the multiple realities encountered in the context. As the inquirer and participants become more sophisticated and knowledgeable about the investigation, they determine when the formal investigation should cease. This usually occurs when information redundancy is apparent. At this point, when no new perspective or information is useful, then the problem under investigation has been bounded.

This evolving design requires a specific method for identifying potential data sources. Purposive sampling, not representative (random) sampling, is needed to achieve the maximum variation of multiple perspectives in an emergent inquiry. This type of sampling for both participants and research sites is chosen when ‘one wants to learn something and come to understand something about certain select cases without needing to generalize to all such cases” (Patton, 1980, p. 107). This strategy is necessary to increase the scope and range of the data exposed in the search for multiple realities. Purposive sampling is responsive to local conditions in that the sampling frame can be identified based on the mutual shaping and values identified in the context. The typical, extreme, political, and convenient cases (Patton, 1987) are generally selected for inclusion in the sample. According to Skrtic (1985a), different types of sampling may occur at different stages of the process to serve different emerging purposes as the inquiry evolves. In the beginning the “typical” cases might be selected to understand the depth and range of the issue under investigation. Later the “extreme” and “political” might be selected to bound the focus. Finally, “convenient” cases might be selected to push for data redundance while also assuring research feasibility.

Data Collection

Once potential data sources are identified, formal constructivist data collection can begin. Qualitative methods are preferred because of their intersubjective focus and adaptability in dealing with multiple, less aggregatable realities, which are of interest to constructivists. The qualitative skills of looking, listening, speaking, and reading found in normal, effective communication must be honed into specific data collection, recording, and analysis skills. The researcher entering into a constructivist inquiry should be prepared to undertake interviewing, observing, recording, and analysis of nonverbal communication and artifacts, depending upon what seems most appropriate as the inquiry emerges. The trained social worker will note that each of these qualitative methods has much in common with the purposeful interview and assessment practices utilized in most social work interventions in micro or macro practice.

These methods are capable of exposing more directly the nature of the transaction between the investigator and the participants because they accommodate multiple, conflicting realities, and are sensitive to interaction and mutual shaping influences essential for co-construction to occur.1 The context for this occurrence is the ever more sophisticated teaching and learning of the hermeneutic circle (Guba & Lincoln, 1989). In addition, qualitative methods make it easier to access the biases of the investigator because, with most qualitative methods, all perspectives are more explicit.

The human instrument is the primary data gathering instrument in cons...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Original Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- SECTION I Thinking about Constructivism

- SECTION II Doing Constructivist Research

- SECTION III The Results of Constructivist Inquiry

- SECTION IV A Research Example

- Glossary

- Further Readings

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Social Work Constructivist Research by Mary Katherine O'Connor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Mental Health in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.