- 186 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Using Comic Art to Improve Speaking, Reading and Writing

About this book

Using Comic Art to Improve Speaking, Reading and Writing uses children's interest in pictures, comics and graphic novels as a way of developing their creative writing abilities, reading skills and oracy. The book's underpinning strategy is the use of comic art images as a visual analogue to help children generate, organise and refine their ideas when writing and talking about text.

In reading comic books children are engaging with highly complex and structured narrative forms. Whether they realise it or not, their emergent visual literacy promotes thinking skills and develops wider metacognitive abilities. Using Comic Art not only motivates children to read more widely, but also enables them to enjoy a richer imagined world when reading comics, text based stories and their own written work.

The book sets out a range of practical techniques and activities which focus on various aspects of narrative, including:

- using comic art as a visual organiser for planning writing

- openings and endings

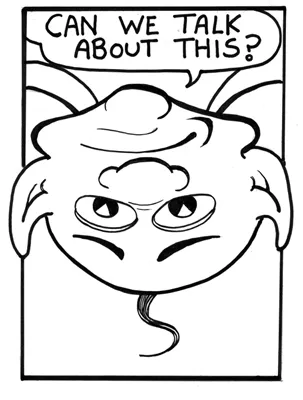

- identifying with the reader, using different genres and developing characters

- creating pace, drama, tension and anticipation

- includes 'Kapow!' techniques to kick start lessons

- an afterword on the learning value of comics.

The activities in Using Comic Art start from this baseline of confident and competent comic-book readers, and show how skills they already possess can be transferred to a range of writing tasks. For instance, the way the panels on a comic's page are arranged can serve as a template for organising paragraphs in a written story or a piece of non-fiction writing. The visual conventions of a graphic novel – the shape of speech bubbles or the way the reader's attention is directed – can inform children in the use of written dialogue and the inclusion of vivid and relevant details.

A creative and essential resource for every primary classroom, Using Comic Art is ideal for primary and secondary school teachers and TAs, as well as primary PGCE students and BEd, BA Primary Undergraduates.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction: Comic Art as a Visual Organiser for Planning Writing

- 1. Strong Openings

- 2. Opening Lines

- 3. What do you want the Reader to See?

- 4. Details Add to the Tension

- 5. Jump into the Action

- 6. Small, Important Details

- 7. Drawing as Visual Shorthand

- 8. Scripting

- 9. Strong Endings

- 10. Creating Quick Characters

- 11. Don’t take that Tone with Me!

- 12. Heroes and Villains

- 13. Controlling Pace

- 14. Build Up the Drama

- 15. Anticipation

- 16. Genre

- 17. Using Kapow! Techniques for Art Appreciation

- 18. Kapow! Techniques and Non-Fiction Writing

- 19. A Note on Rough Layouts

- 20. Afterword – the Learning Value of Comics

- Bibliography

- Index