- 344 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Transition From Prelinguistic To Linguistic Communication

About this book

Published in the year 1983, The Transition From Prelinguistic To Linguistic Communication is a valuable contribution to the field of Developmental Psychology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Transition From Prelinguistic To Linguistic Communication by R. M. Golinkoff in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Developmental Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 In the Beginning Was the Word: A History of the Study of Language Acquisition

University of Delaware

The study of language acquisition has grown disproportionately as compared to other areas of developmental psychology within the last 10 years. Research has proliferated because language acquisition has become incorporated into many different areas within a range of disciplines, sometimes to the point of submerging key issues. A primary goal of this volume is to retrieve language acquisition from these scattered directions and to reflect on the broadening of its concerns.

The purpose of this introductory chapter is to give an account of the expansion and diversity characterizing current research and to evaluate whether the broadened focus of recent years has added anything substantial to our understanding of language acquisition. To accomplish this goal we provide a brief, non-exhaustive historical overview of how the field of language acquisition has evolved in the past 20 years. This leads to a critique of issues that have been either presupposed or ignored, such as the importance of the transition period from pre-linguistic to linguistic communication. We conclude by pointing out future directions that appear promising with respect to critical issues in language acquisition.

Our historical account borrows a novel form; we present a “creation science” view of language acquisition, designed to parallel the seven days of creation. On each day of creation, the theoretical focus of language acquisition changed and as a by-product, the nature of the linguistic (or nonlinguistic) unit considered worthy and appropriate for study also changed. Just as the seven days in the creation of the world, seen metaphorically, encompass events by telescoping them, the field of language acquisition may be understood by segmenting into separate periods the scholarly progression of ideas in the past 20 years.

The First and Second Days of Creation: The Revelation of Generative Transformational Grammar

On the first day the deity created Chomsky. On the second day Chomsky— without the deity's help—created generative transformational grammar. This event occurred in 1958 with the publication of Syntactic Structures, Chomsky's dissertation, which caused a revolution in the field of linguistics (Searle, 1972). Certainly Chomsky did not create the field of child language, any more than Crick and Watson created the field of molecular genetics when they unraveled the genetic code. However, just as Crick and Watson's work reoriented the research of a generation of geneticists, Chomsky's work renewed and invigorated the field of language acquisition. What Chomsky did was to postulate a biologically programmed, species-specific universal model of language that others used as their theoretical base to explain the regularities which seemed to appear in child language. Chomsky's beliefs gained additional power with the publication of Lenneberg's (1967) influential volume which argued for the universality of the order and timing of acquisition across radically different languages, as well as mastery of language essentials among all children regardless of intelligence.

In reviewing the biological bases and evolutionary evidence for language as a species-specific signal system, Lenneberg (1967) began by writing that “reason, discovery, and intelligence are concepts that are as irrelevant for an explanation of the existence of language as for the existence of bird songs or the dance of the bees (p. 1].” Research by Marler (see Marler, Dooling, & Zoloth, 1980, for a review) on how birds learned their song did in fact seem to support this assertion. Marler found that if two types of sparrows are kept in isolation where they can hear no bird song during a critical period of exposure to song between 20 and SO days of age, they will sing an abnormal, garbled song when they reach maturity. However, if isolated sparrows hear artificially combined elements of bird songs, parts of which do and parts of which do not match their species' song, they will sing a version of their species song when they reach maturity, approximately 300 days after their exposure to the artificial song. This finding suggests the existence of a template for the species song which is activated only under exposure to song—even unnatural, artificially constructed song. Parallels with human language acquisition are tempting to construct; Lenneberg (1967) argued strongly for a critical period of exposure to language, for its species-specificity and for its appearance among virtually all members of the species exposed to language. In other words, the idea that the capacity for language was prewired into the human brain, destined to emerge as the organism matured biologically, seemed to support Chomsky's views and was Lenneberg's contribution to the study of language acquisition.

As a farewell to behaviorist accounts of language acquisition, Lenneberg's book also opened up the possibility of an interdisciplinary approach to language study which could incorporate not only psychology and linguistics, but neurobiology and language pathology as well. “Language” was not equivalent to “speech” since it resided in the unique capacities of the human brain; disruption of speech could still permit language.

The theoretical weight and apparent empirical evidence behind Lenneberg's arguments combined with the paucity of methods available to investigate what Chomsky had called “competence” and “deep structure” often led psychol-ogists to presuppose innateness as a solution to the problem of language acquisition. Although many researchers had interpreted statements by Chomsky (1965) as a blanket endorsement of a radically innatist position, Chomsky had in fact said, “any [evaluation] proposal… is an empirical hypothesis about the nature of language … we are very far from being able to present a system of formal and substantive linguistic universals that will be sufficiently rich and detailed to account for the facts of language learning [p. 46].” (See Piatelli-Palmerini (1980) for a recent formulation of Chomsky's position on language acquisition.)

The Third Day: Language Acquisition as the Acquisition of Syntax

On the third day Miller (1962) appeared and brought down to the psychologists tablets on which were inscribed the highlights of generative grammar. For lack of good theory psychologists had for the most part relegated the study of language and language acquisition to a minor position within their science. Here was Miller interpreting a rich, though elusive, theory to guide psychologists in their inquiry. At the same time, Braine (1963) claimed that children possessed a puerile version of the adult language model which he called “pivot-open grammar.” Brown and Bellugi (1964), Miller and Ervin (1964), and McNeill (1966) all posited some version of a grammar in an attempt to account for children

Although it is easy in retrospect to criticize developments on the third day of creation, that is, why an exclusively syntactic approach failed for both adult sentence comprehension (see Fodor, Bever, & Garrett, 1974) and children”s early production (see Brown, 1973), developments on the third day should be seen in the context of the prevailing Zeitgeist. Many psychologists were not ready to abandon behaviorist accounts of cognitive processes, including lan-guage. That children under 2-years-of-age had themselves either induced or were endowed with grammatical rules and mysterious “deep structures” seemed to be heretical assertions. Thus, although the exclusively syntactic approach discussed earlier was eventually abandoned, these new ideas on language, in combination with other developments in what was not yet called “cognitive” psychology, were to change the landscape of the science of psychology.

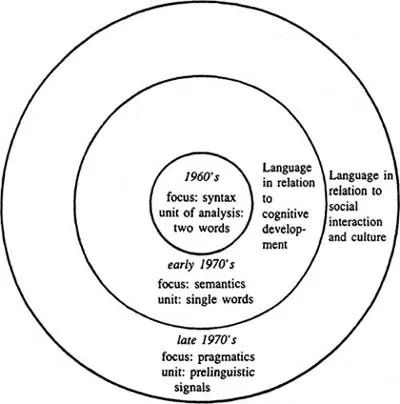

Fig 1.1 Concentric circles represent the ever-widening view of language acquisition seen from an historical perspective.

The Fourth Day: The Reincorporation of Semantics into Child Language

On the fourth day (see the next larger circle in Fig. 1.1) Bloom (1970), Keman (1970), Schlesinger (1971), and Slobin (1969) incorporated semantics into the study of language acquisition. Now not only the form but the content of children's earliest utterances was scrutinized. Developments in psycholinguistics and linguistics moved independently in mis direction as well. For example, the “derivational complexity” issue (Fodor, Bever, & Garrett, 1974), which first appeared on the third day, was sacrificed on the altar of semantics. That is, the notion that the difficulty of comprehending a sentence should be linearly related to the number of transformations that the sentence contained was not true; sentence meanings could override the number of transformations, making some derivationally complex sentences easier to comprehend than some derivationally simpler sentences. In addition, theoretical linguists such as Chafe (1970) and Fillmore (1968), while basically accepting Chomsky's transformational view, seriously questioned whether deep structure contained more world knowledge than Chomsky seemed to grant in his 1965 version or indeed whether the notion of a deep structure was needed at all (McCawley, 1968).

The assertion that children possessed more knowledge of the world than their limited surface structures expressed caused researchers to expand their interpretation of 2- and 3-word utterances, and finally to examine single-word utterances (Greenfield & Smith, 1976) using the method of “rich interpretation.” As Bloom (1970) and others astutely noted, the very same surface structure (e.g., the now famous “Mommy sock”) could mean completely different things depending on the context in which it was uttered. What was so appealing about this account for many psychologists was that the study of the tacit, often inchoate knowledge of the world encoded by language was just what many psychologists (although not many linguists) called their life's work. Psychologists strongly believed in the power of context and task for determining perception, e.g., the perception of ambiguous figures; memory, e.g., intentional versus incidental learning; and reasoning, e.g.. functional fixedness. Why shouldn't young children rely on context to convey meanings which their undeveloped linguistic skills prevented them from completely communicating?

Now children's early verbal productions were taken to reflect considerable world knowledge. Using this argument, early productions could be profitably studied even before two words appeared, since the concepts underlying these early utterances were an outcome of sensorimotor achievements such as object permanence and causal inference. Specifically, children's ability to encode case role concepts which specified such things as who did the action (the agent), who received the action (the patient), and where the action took place (location), received some support from perceptual research (see Golinkoff, 1981a, for a review) as well as from the broad outlines of Piaget's theory.

Instead of Chomsky's (1980) “Cartesian theory of mind” in which the in-fant's mind is compared to “a function that maps experience onto a steady state [p. 109]”, Piaget's constructivist account stressed the infant's activity in selecting from experience and constructing first, conceptual, and then linguistic structures. Piaget (1951) proposed to incorporate language into the semiotic function which included symbolic play, deferred imitation and mental imagery. Thus, the cognitive hypothesis placed language acquisition in a general developmental framework that provided an alternative to earlier innatist views.

While the field turned away from linguistic nativism in that linguistic univer-sal became cognitive universals, e.g., McNeill (1970), Slobin (1973), the lin-guistic environment available to the child was still seen only as providing infor-mation about the child's specific language community. The prevailing view of the child was as an hypothesis tester (Fodor, 1966) and solitary constructor of a language which mapped onto preexisting concepts. The acquisition of syntax was reduced for some to the acquisition of linguistic devices to map onto world knowledge.

Thus, on Day 4 the child's cognitive resources seemed sufficient to account for the acquisition of both the semantic underpinnings and the syntactic struc-tures of language. Disenchantment with this position occurred when cognitive structures were not invariably found to precede linguistic structures or even to be closely linked (e.g., Beilin, 1975; Corrigan, 1979).

The Fifth Day: The Social-Functional Approach to Language Acquisition

On the fifth day, “pragmatics,” or the “functions of signs in context” (Morris, 1946), represented by another circle in Fig. 1.1, caused language acquisition to be thought of as embedded in a social and cultural context. Children didn't just learn language, mysterious as that task alone might be, they learned a social system and how language functioned within it. For example, they learned forms bf address, ways of asking, and other sociolinguistic rules that varied by culture and that defined a competent speaker in that culture. At that time Bruner (1974) wrote:

Neither the syntactic nor the semantic approach to language acquisition take sufficiently into account what the child is trying to do by communicating. As linguistic philosophers remind us, utterances are used for different ends and use is a powerful determinant of rule structures … one cannot understand the transition from pre-linguistic to linguistic communication without taking into account the uses of communication as speech acts [p. 282].

Ervin-Tripp and Mitchell-Keman (1977) also speculated that without attending to the functions language served for the young ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1 In the Beginning Was the Word: A History of the Study of Language Acquisition

- 2. The Acquisition of Pragmatic Commitments

- 3. On Transition, Continuity, and Coupling: An Alternative Approach to Communicative Development

- 4. The Preverbal Negotiation of Failed Messages: Insights into the Transition Period

- DISCUSSION

- 6. Setting the Stage for Language Acquisition: Communication Development in the First Year

- 7. A Cultural Perspective on the Transition from Prelinguistic to Linguistic Communication

- DISCUSSION

- 9. The Redundancy Between Adult Speech and Nonverbal Interaction: A Contribution to Acquisition?

- 10. Feeling, Form, and Intention in the Baby's Transition To Language

- DISCUSSION

- 12. Implications of the Transition Period for Early Intervention

- 13. Early Stages of Discourse Comprehension and Production: Implications for Assessment and Intervention

- 14. Why Social Interaction Makes A Difference: Insights from Abused Toddlers

- DISCUSSION

- DISCUSSION OF THE VOLUME

- DISCUSSION OF THE VOLUME

- Author Index

- Subject Index