![]()

PART I

Theoretical perspectives and methodologies

![]()

1

ANALYSING SPORT POLICY IN A GLOBALISING CONTEXT

Ian Henry and Ling-Mei Ko

Introduction

The literature in policy analysis has traditionally incorporated a wide range of foci; for example, in the study of policy institutions, policy processes and policy outcomes (Parsons, 1996). It encompasses both analysis for policy (i.e. analysis that makes a direct contribution to the policy process, clarifying the criteria against which policy is to be judged or enhancing decision-making against agreed criteria) and analysis of policy (i.e. the study of the policy process itself and explanation of how the policy process operates, considering for example issues such as in whose interests does policy operate, and to what ends; Ham and Hill, 1993).

The scale of policy analysis also varies from the micro level often associated with understanding the nature and impact of incremental change in a specific context; to the meso level which may focus on policy making within a limited cultural, social, political or economic horizon; to macro-level concerns with global phenomena or with widespread, general or ‘universal’ impacts such as feminist concerns with impact of policy on gender relations (Marshall, 1999).

The range of concerns outlined above has become increasingly evident in the sport policy literature, interest in which has grown rapidly over the last decade or so. The appearance of articles on sport in journals addressing generic policy domains, and of a significant journal dedicated specifically to the analysis of sports policy (The International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics), bear witness to the growing volume of the literature, the diversity of theoretical bases on which it draws, and its widening comparative, international and transnational foci (Bergsgard, Houlihan, Mangset, Nødland, and Rommetvedt, 2007; Green and Houlihan, 2005b; Henry, Al-Tauqi, Amara, and Lee, 2007).

However, rarely has the range of methodologies, theoretical orientations and geographical foci been explicitly considered, in particular in relation to sports policy. This book seeks to redress this imbalance, focusing on different disciplinary and theoretical traditions, different methodological foundations both in terms of methods adopted and the ontological and epistemological foundations or assumptions on which such methods are based, and different geopolitical constituencies, bridging the analysis ‘for’ and analysis ‘of’ policy approaches.

Analysis ‘for’ sport policy and analysis ‘of’ sport policy

The distinction we note above, between analysis for/of policy seems to imply two polar opposites, but this is an unhelpful claim. Underlying this notion of ‘two poles’ of policy analysis is an oversimplification of the distinction between theory and practice. Much of the work undertaken in the field of sports policy is undertaken to directly inform, enhance and justify particular sports policies or programmes of action. Policy evaluation to inform the implementation of policy is a classic example. However this is not to say that such approaches are not informed by theory – theories of power, theories of social change, theories of policy formulation and implementation. Indeed we would argue that no practical statement is completely free of theoretical implications.

While practice cannot be theory-independent, theory itself, particularly social theory, carries with it practical implications. This was famously reflected by Kurt Lewin in epigrammatic style when he suggested that ‘there is nothing so practical as a good theory’ (Lewin, 1951: 169). This statement may have reached the status of platitude in the contemporary context, but some theorists, critical theorists for example, would claim that one of the criteria on which a theory should be judged is its potential to make a positive practical improvement to the real world, its emancipatory potential. Thus, we would argue that it is more appropriate to see this distinction between analysis of and for policy as a continuum, and that the contributions to this book reflect the full range of types of contribution one might expect to see even though the contributors to the volume are largely drawn from the academic world rather than that of policy practitioner.

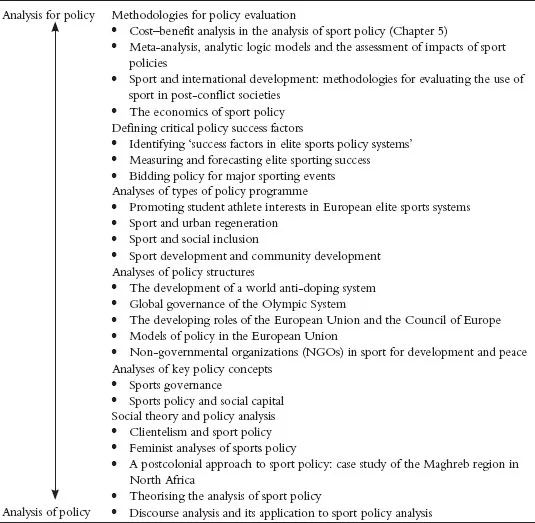

Figure 1.1 Selected examples of approaches to sports policy analysis in this collection

Theoretical (and meta-theoretical) foundations of sports policy analysis: a typology of approaches to sports policy comparison

Much of the work incorporated in this book is (either explicitly or implicitly) comparative. Indeed, as Durkheim remarked, all social analysis is comparative even if it deals only with a single case since analysis invariably deals with how unique or typical a particular case is. We have argued elsewhere that comparative analysis in sports policy can be encompassed within a fourfold typology (Henry et al., 2007), and Table 1.1 summarises the allocation of studies to this typology, though individual studies may overlap between these ideal type descriptions.

The first of the types we term ‘seeking statistical similarities’ in which, at its simplest level, descriptive statistical approaches seek to identify the similarities between policy systems. This might address research questions such as ‘what are the main features of the sports systems that enjoy the highest levels of adult participation in sport’, seeking to identify the characteristics of national systems that have high and low levels of participation. Such an approach for example underpinned the COMPASS project (Compass, 1999), a partnership between researchers in a number of European states that sought to ascertain the nature and level of statistical association between adult participation rates in sport as a variable, with a range of other variables, whether economic (e.g. level of GDP per capita; level of per capita spending on sport), cultural (distinctive cultures in Scandinavia, Northern and Southern Europe, Europe), political (centralised versus decentralised policy systems) or organisational (sports policy systems which are public sector, commercial sector or voluntary sector led). The aim of this type of approach is to produce accurate statistical operationalisation of key factors related in this case to participation, and to develop nomothetic, law-like generalisations about the association of participation with such factors in order to develop explanations of why some national sports systems produce greater levels of participation than others.

Table 1.1 Chapters exemplifying different types of comparative analysis of sport policy in this collection

| Comparative Type | Exemplars |

| Type 1: Seeking similarities statistically | • Methodologies for identifying and comparing success factors in elite sport policies (Chapter 16: De Bosscher et al.) |

| | • Measuring and forecasting elite sporting success (Chapter 17: Shibli et al.) |

| Type 2: Describing difference | • Sport and urban regeneration (Chapter 22: Paramio Salcines) |

| | • Clientelism and sport policy in Taiwan (Chapter 13: Lee and Jiang) |

| Type 3: Theorising the transnational | • Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in sport for development and peace (SDP) (Chapter 8: Mwaanga) • A postcolonial approach to sport policy: case study of the Maghreb Rregion in North Africa (Chapter 25: Amara) |

| Type 4: Defining discourse | • Discourse analysis and its application to sport policy analysis (Chapter 3: Piggin) |

The approach however faces major difficulties in terms of the measurement and application of variables at national levels. A major difficulty is that data are not always produced by national systems in truly comparable ways. Thus differences in the way adult sports participation is measured, or in the way governments sports expenditures are accounted for, the extent and nature of types of decentralisation and so on, are so great that meaningful statistical comparison becomes at best difficult and at worst positively misleading. Furthermore, even with statistically significant relationships between the dependent variable and other independent variables, this does not of itself constitute an explanation of the relationship between them, which will often require qualitative research approaches to develop a convincing account of the nature of causal or mediating relationships explaining levels of adult participation. In short these type 1 approaches suffer from the traditional limitations of positivist analysis.

A key problem for such approaches is the ‘black box’ problem, where statistical measures of policy inputs (e.g. financial and human resources) and of outputs (rate of adult participation), and the levels of statistical association between them, are known but the explanation of how the input variables result in changes in the output variable, is ‘hidden’ within the black box of policy process. In order to understand how the policy system is able to convert inputs into outputs we need some detailed account of how the policy system works – how the policy system is shaped, of the nature, range and interaction of interest groups and elites in the deciding of policy priorities, and so on. Statistically significant associations of themselves do not constitute explanations of how outcomes are achieved.

Although there are limitations of this type of approach, there are significant potential benefits also since it allows the researcher to summarise relationships across a large number of policy systems. Perhaps the best-known and most rigorous attempt to apply a type one approach in recent years has been that by De Bosscher and her colleagues (De Bosscher, De Knop, and Heyndels, 2003), who have focused on developing a framework by which to explain the dependant variable of ‘national success in elite sporting performance’. They have developed the SPLISS framework (Sports Policy factors Leading to International Sporting Success) which identifies nine ‘pillars’ of sporting success (see Chapter 16), each composed of a range of operational indicators. Notwithstanding the sophistication of their approach and the development of batteries of indicators rather than reliance on a small number of higher level indicators, the approach still has to overcome the difficulties of explaining why and how these inputs achieve the measures of elite sporting success that they do, which requires some detailed qualitative analysis of policy systems.

The second type of policy comparison we have entitled ‘describing differences’ to maintain the use of alliteration in their naming of types, but which also involves describing differences (and similarities) in policy systems. Such an approach involves the use of middle-range accounts often based on ideal typical accounts. Houlihan and Green in their various accounts of comparative policy and policy change present such an approach in for example Houlihan’s analysis of similarities and differences in policy systems in Bergsgard et al. (2007), Green and Houlihan (2005b) and Houlihan (1997).

Houlihan and Green’s use of ideal types is perhaps even more explicit in their adoption and testing of middle range theoretical accounts of policy change involving for example the advocacy coalition framework (Houlihan and Green, 2006). Other examples from within this book would include Lee and Jiang’s development of political clientelism as an explanatory frame to account for the development of policy in Taiwanese sport.

A key issue for such approaches is the extent to which they move beyond the descriptive to identify ‘real’ structures underpinning sport policy. In essence this is a debate between interpretivist and constructivist approaches on the one hand, and realist/critical realist claims on the other. The latter lays claim to identifying real structures that may be socially constructed but that exist independently of the actors who constructed them, and that exert causal influence in the sense of enabling and constraining certain forms of social (in our case policy) action.

The third type is that of ‘theorising the transnational’, referring to those studies that go beyond national level analysis to locate their accounts of policy development in the context of theories of global change. A range of the chapters in this book relate to transnational analysis. Oscar Mwaanga’s account of the nature and role of NGOs in the international development through sport movement (Chapter 8) is one such example. In addition, in terms of seeking to develop an explanation of the transnational influences on national sports systems by reference to post-colonial perspectives on policy development, Mahfoud Amara’s research on the development of sport policy systems in the Maghreb region (Chapter 25) represents a theoretically informed analysis of the development of policy systems within the context of a wider transnational theoretical frame. This approach has the strength of not constraining explanation of policy formation and change by reference to a local or national frame but recognising the influence of (and influence on) global factors in relation to local policy outcomes.

The fourth and final type of approach to analysis of policy systems we had termed ‘defining discourse’ and is related to the recent developments in the study of policy as discourse (Hewitt, 2009; Leow, 2011). The use of this label is intended to encapsulate a double meaning. It refers to both the ways in which some discourse analysts see discourse as reflecting underlying ways of seeing, explaining, or understanding a particular policy context, policy problem or policy action, that is reflecting realities or different actors’ understandings of those realities. Here, discourse is a reflection of the individual or group’s perception of policy realities, and the researcher’s task is to define the nature of those different reflections by defining the discourse that relates to them. A key concern here is often with identifying ‘power over discourse’, explaining whose account (and thus whose values) are dominant.

The second meaning relates not to whether the discourse used reflects the ways in which actors understand policy but rather how discourse determines the way they do so. Discourse in this sense defines reality. In this second somewhat more radical approach to discourse analysis the researcher is often more concerned with the ‘power of discourse’, its ability to define policy realities.

The application of discourse analysis to sport policy analysis is the focus of Piggin’s discussion in Chapter 3. He identifies ways in which discourse analysis of different types allow for the identification of how dominant and subordinate voices in policy debates reflect/reproduce the nature of dominant interests in that process.

This brief discussion of types of approach to the analysis of sports policy serves to illustrate the rich vein that runs through work in this field and, we would argue, is represented in the nature of the contributions to this book.

Ontological and epistemological premises of policy analyses and policy evaluations

One set of issues that is rarely explicitly addressed even in those studies that fall at the ‘analysis of policy’ end of the spectrum of policy analysis, relates to the ontological and epistemological positions adopted in particular studies and the consequences of these positions for the application of the analysis. We have discussed this in more detail elsewhere (Henry et al., 2007; Henry, Amara,...