![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

The age of the girl

An intense and diverse lode of cultural and journalistic material has been produced about girls in contemporary Japan, escalating in volume particularly from the 1980s to 2010s. This book analyses this cult of girls and takes as its core case study social panic and media delight about delinquent schoolgirls in the second half of the 1990s. The prolific outpouring of girl material reflected the convoluted and tricky male reaction to further realms believed to be lost to gender equality and female emancipation. These were under-employment and the loss of privileges and security in the workplace, which have been bound up with the restructuring of the postwar Japanese labor system in a period of extended recession extending from the early 1990s. Accompanying the erosion of wages and onset of labor insecurity (Ishida and Slater, 2010) were losses of expected service, care, and reproduction in the home through the consequential unraveling of the established and dependent bolster of under-paid part-time female labor and dedicated housewifery. The conflicted, nostalgic, pornographic, and at times, racialized manner in which largely male sentiments about this transformation have been expressed, and the flamboyant and stylistic manner in which young women have reacted to the weight of an obsessive and accusatory male media gaze in the 1990s and 2000s, are the substance of this book. See teenage female expression in Figure 1.1.

Pornographic by means of tortuous metaphors (“loose socks” or “loose sex”?) and greased with juvenile smut, material about girls has rarely excluded a dosage of visceral titillation. This is not to say that the staging of girls’ bodies in culture is commensurate simply with the servicing of personal and compensatory “pornotopias” (Marcus, 1966). Though hunched, perhaps, behind the voyeurism and insistent vulgarity of girls staged in the various lacunae of male subculture, the ghost of sexual starvation does not provide an explanation for the convoluted narratives, sarcastic jokes, elaborate physical appearances, and peculiar metamorphoses of animated girls from the late 1980s through to the present, nor does it explain the intricate code of meanings underlying the news-reportage on sexually and financially independent high-school girls in the mid to late 1990s.

FIGURE 1.1 Girls with up-to-the-minute caramel-colored hair and platform boots (atsuzoku) posing in Shibuya in 2003

Source: photograph by Sharon Kinsella.

The popularity of both official (cute and sanitized) and underground (pornographic, iconoclastic, and anti-bourgeois) images and narratives about Japanese schoolgirls, imported and reinvented overseas, suggests that the type of multivalent, ambivalent, and avenging postures projected onto girls in Japan—and the underlying structures of feeling operating behind those projections—have a resonance in other societies that are experiencing different versions of the same disintegrating social totality (Tiqqun, 2012) and disordering of labor, family, reproduction, and gender but that are less able or willing to evolve explicit cultural tropes and local journalism through which to give form to and disseminate these sentiments. Japan in the 1990s and 2000s became the source of a range of complicated material about sexualized schoolgirls and girls with power, which was broadly cathartic to male viewers and in specific cases hostile to women, but whose precise import and insider ironies could remain obscure, foreign, and conveniently lost in translation. Cute shōjo (girl) and sexy schoolgirl (joshi kōsei) figures have been celebrated as wonderfully, incomprehensibly Japanese and kooky. But the fascination with animated and licentious Japanese schoolgirls in the US and Europe perhaps hints at depths of hidden longing, nostalgia, and resentment of women, that are not otherwise easily discerned in the public sphere in North American and European culture. Hints about the domesticated but unfinished business of difficult gender relations in post-industrial Western states can be gleaned through observing the selective importation of girl iconography from Japan.

Female advancement

Visions of female advancement, whether real or merely anticipated, have permeated culture and public debate in Japan over the past two decades. Journalism has played upon anxious thoughts about the critical retraction of unpaid and underpaid female labor—servicing, reproductive, caring, and sexual—resulting in a generalized “care deficit” (Allison, 2009: 13). The retraction of unrewarded female contributions appeared to be having a corrosive impact on the strength of the family, the labor force, the population, and national morale. Female advancement appeared from across national borders, too, in the form of the multi-state campaign for the financial compensation of former comfort women of Imperial Japan that ran through the 1990s and 2000s. Government-sponsored social research published in numerous white papers showed over and again that women in Japan were not marrying as much (Ōhashi, 1993; Yamada, 1996; Kitamura and Abe, 2007; Tokuhiro, 2009), not having as many children (Ueno, 1998; Schoppa, 2006), and that they were applying to proper four-year universities (Fujimura-Faneselow, 1995; Edwards and Pasquale, 2003) instead of women’s two-year colleges. The divorce rate rose most conspicuously between 1990 and 2005 (from 1.28 to 2.10 per 1,000 of the population). The age of first marriage has also climbed steadily from the early-seventies reaching 28.8 by 2010. The rate of marriage and national birth rates having already declined gradually between the mid-postwar turning point of 1973 and 1990, then dropped again between 2000 and 2010. The national birth rate reached its lowest point on record in 2005 after a five-year slump (at 1.25 live births per 1,000) and marriage rates reached the lowest levels on record of 5.5 per 1,000 in 2010 after two decades of steep decline in the rate of marriage.1 The proportions of young women choosing not to marry or not to have children—which are closely concomitant in this society (Hertog, 2009: 1–4)—have risen in the 1990s and 2000s as the proportion of unmarried men and women (mikonsha) of parenting age has risen without pause. In 1980, 11.42 percent of 35-year-olds were unmarried; in 2010, this had risen to 32.04 percent. Almost half (47.2 percent) of all those adults aged 30 years and under were unmarried, in 2010. In 2010, 28 percent of Japanese women and over 38 percent of Japanese men aged between 25 and 49 years old were unmarried and, unlike their counterparts in Europe, only rarely cohabiting with partners or children (Kokusei chōsa, 1980, 2010).

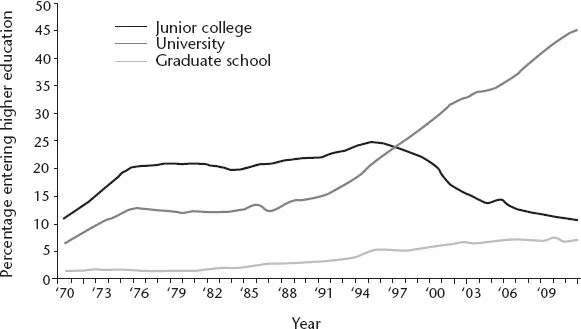

Observe the increases in the rate of young women pursuing university education in Figure 1.2. In 1970, 6.5 percent, and by 1989, 14.7 percent of women were going to university. This figure rose rapidly in the 1990s, almost doubling to 33.8 percent by 2002 and tripling by 2011, when entering university was achieved by 45.8 percent of all young women. The numbers entering graduate school also rose, from 3 percent in 1989 to 6.3 percent by 2000 and 7.1 percent in 2004, and then creeping to a peak of 7.5 percent in 2008. At the same time, the number of women attending a two-year junior college to receive ladylike skills (McVeigh, 1996) slipped by one-third, from 22.1 percent in 1989 to 10.4 percent in 2011.2 Ironically, young women in the 1990s and 2000s began to attain the university education required to compete directly with young men for what was a simultaneously shrinking number of secure graduate jobs as full-time company recruits. With and without degrees, however, women were struggling to find employment and to stay in the workforce despite the pressure of low wages linked to part-time and non-permanent employee status and the largely maintained exclusion of women from managerial track positions with corresponding higher salaries. The proportion of women in pure employment (excluding work in family businesses and housewifery) has steadily risen from 26.9 percent in 1975 to 37.9 percent in 1995, and to 40.8 percent in 2010. The White Paper on Gender Equality (Danjō Kyōdō Sankaku Hakusho) introduced in 1998 attempted to monitor a transition in Japanese gender relations, and can be considered symptomatic of government goals to channel the “active participation of women” into the “revitalization of economy and society” (Danjō Kyōdō Sankaku Hakusho, 2010: 10). At ministerial levels, capturing the energy and skills of young women has been viewed as critical to the healing and cohesion of a more flexible society that could weather the recession and economic restructuring.

FIGURE 1.2 Graph depicting the rate of girls entering university from 1970 to 2011

Source: Fujin Hakusho (~1999), Josei Rōdō Hakusho (2000–2002), Danjo Kyōdō Sankaku Hakusho (2001–2011).

Lack of male advancement and economic recession

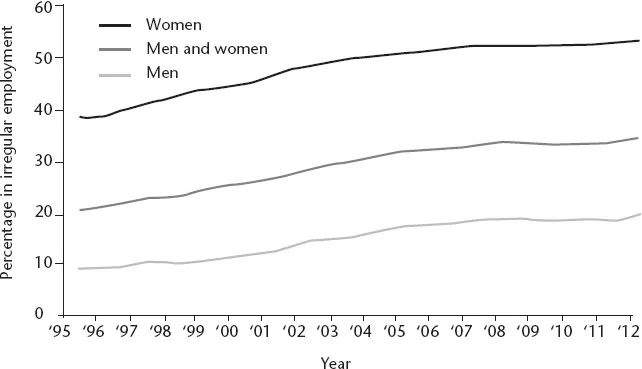

The effects of the collapse of the financial bubble of the 1980s at the end of that decade began to shake through the economy and society in the early 1990s, and crystallized in full-blown economic recession, rising unemployment and a freeze on hiring new recruits from universities from 1995. The “employment ice age” (koyō hyōgaki), extending from 1995 into the 2000s, forced previously securely employed cohorts of male high-school and college graduates into a permanent cycle of irregular (hiseiki), part time (paato), temporary (arubaito), and contract (haken) work, strung between bouts of unemployment, giving rise to contemporary social problems, from youth poverty, unmarried adults cohabiting with parents (“parasite singles”), the working poor, and reports of widespread stress, heavy workloads, and minimized workplace training for those gaining full-time employment (Genda, 2006, Suzuki et al., 2010). Critical academic analysts estimated that the rate of unemployment in 1995 was as high as 8.9 percent (Kishi, 1995: 290), though it increased most sharply from 1997 onwards, affecting younger men and school-leavers not attending college disproportionately. From another perspective, the male labor force participation rate fell to an all-time postwar low of 63.3 percent in 1998 (Kōsei rōdō hakusho, 1999). While the proportion of men channeled into irregular employment increased steadily in the 1990s, reaching 14.8 percent by 2002, women fully absorbed a greater part of the growing demand for cheap and flexible irregular employment—50.7 percent of all female employment was “irregular” by 2002. (See the movement of men and women into the irregular employment pool in Figure 1.3.) Interestingly, through the 1990s and 2000s the wages of part-time and irregular male employees began to drop behind those of both full-time male employees and those of the small but emerging cohort of fulltime and permanent female employees, whose wages steadily rose through this period and tracked those of their full-time male colleagues. By the 2000s the wages of part-time male employees were closer to those of their female counterparts than those of other men: gender-based wage inequalities systematized within the twentieth century labor market had been partially redistributed and de-gendered within the ballooning pool of irregular employees (Genda, 2006; Ishida and Slater, 2010). Thought provoking shifts in wage levels can be examined in detail in Figure 1.4. Rising unemployment and poverty linked to irregular employment impacted on the potential of younger generations to “envision a stable life-course” (Suzuki et al., 2010: 513) and generated “widespread anxiety” and a potentially exaggerated sensitivity to unequal developments: “Emblematic of this vague, amorphous uneasiness is the concern over widening economic disparities” (Genda, 2006: 2).

FIGURE 1.3 Graph illustrating the growth of irregular employment among men and women from 1995 to 2012

Source: Josei Rōdō Hakushō 2004:82; figures continued in Hataraku Josei no Jitsujō Heisei 23/2012, sourced online at: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/koyoukintou/josei-jitsujō/dl/11b.pdf.

Girl cult in the media

From the 1980s to the 2010s both mass media and underground culture mirrored government policy-making, in the sense that it too was dominated by the vision of ranks of able, heroic, and energetic young women. In the expanding spheres of communications, advertizing, television, and new digital visual media, the exuberant faces and voices of robotic little girls bouncing with energy became the messengers, voices, and actors. The single most widely broadcast animation and lyrics at the start of the 1990s were “pi-hyara, pi-hyara,” the lusty nonsense chorus of a ditty sung by the willful and eccentric animated girl character “Chibi Maruko Chan” (Little Miss Chubby Cheeks; Yamane, 1993: 12). Cultural critic Saitō Tamaki goes on to estimate that about 80 percent of the most popular animations produced in Japan in the 1990s featured some version of the beautiful fighting girl (bishōjo senshi) character at its core (Saitō, 1998: 8). The image of an alert and intelligent schoolgirl with short, cropped hair avidly reading the news, which featured in an Asahi Shinbun poster advertisement in 2003, was symptomatic of the widespread anticipation of an informed teenage female initiative, that was widely presumed to be imminent in this period. In fact, smart young women in business suits or school uniform were the recurrent characters of adverts for broadsheet newspapers throughout the late 1990s and 2000s. The slogan of this advertisement was “Read, Think, Gain Power: Power Paper Asahi Shinbun” (Yomu, kangaeru, chikara ni naru: Power Paper, Asahi Shinbun). Commenting on teenage girls’ consumption and cultural activity over the preceding decade, the director of social research at the highly regarded Hakuhodo Institute (HILL) suggested that in the midst of the long Japanese economic recession, schoolgirls had displayed an “unanticipated vitality” that ought not be criminalized but channeled instead—commercially, that is—for its energizing and healing (“iyasu”) potential (Sekizawa Hidehiko interview, 24 October 2002). Through the recent historical period in which the male cult of ...