- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Language Development In Exceptional Circumstances

About this book

Ever since attempts were made to describe and explain normal language development, references to exceptional circumstances have been made. Variations in the conditions under which language is acquired can be regarded as natural experiments, which would not be feasible or ethical under normal circumstances. This can throw light on such questions as:

*What language input is necessary for the child to learn language?

*What is the relationship between cognition and language?

*How independent are different components of language function?

*Are there critical periods for language development?

*Can we specify necessary and sufficient conditions for language impairment? This book covers a range of exceptional circumstances including: extreme deprivation, twinship, visual and auditory impairments, autism and focal brain damage?

Written in a jargon-free style, and including a glossary of linguistic and medical terminology, the book assumes little specialist knowledge. This text is suitable for both students and practitioners in the fields of psycholinguistics, developmental and educational psychology, speech pathology, paediatrics and special education.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Language Development in Unexceptional Circumstances

Phonology

Grammar: syntax and morphology

Semantics

Pragmatics

Variability in language acquisition

Exceptional circumstances as ‘natural experiments’

Theoretical issues addressed by studying children in exceptional circumstances

Reasons for studying exceptional circumstances in their own right

When psychologists first attempted the task of describing the pattern and course of language development in young children, they used a number of common-sense measures to record observable changes in language behaviour at different ages. McCarthy (1930), for example, in a study of children aged from 2 to 5 years, measured the length of children’s sentences, the frequency of different parts of speech, the number of words in a child’s vocabulary, and the proportion of speech that was used for social and non-social purposes. The picture of language development that emerged was one of gradual increase in verbal skill as children added new items to their language repertoire, reducing the number of errors in their speech, and gradually narrowing the gap between their imperfect imitations and the adult models to which they were exposed. In the early 1960s, however, the study of child language was transformed in conception and approach under the influence of linguists, who argued that research on language acquisition had largely ignored developments in linguistics, and had, as a result, been quite inadequate at portraying the nature of the task that faced children acquiring language.

Methods of linguistic analysis and description had already been applied to different aspects of child language in diary studies of individual children (Leopold 1939, 1947, 1949a, 1949b, Velten 1943), but these were not widely known nor easily comparable with the psychological descriptions. When psychologists began to adopt linguistic methods, the hybrid discipline of developmental psycholinguistics was born, and a different picture of language development began to take shape. To a linguist, one of the most fundamental notions about language is that it is a system organized in a regular and predictable way such that it is possible to write a set of rules that describes the regularities of the system. Rather than documenting verbal errors, which gradually decrease with age, linguists approached children just as they would approach speakers of a hitherto unknown language, treating their verbal productions as evidence of a language system susceptible to linguistic analysis and description. This approach to language acquisition meant that the process could then be described as a series of structural changes within a system that could be inferred from observing and recording the child’s attempts to understand and express meaning through language. There are a number of different levels on which the system may be said to be organized, each dealing with a different unit of analysis. These are phonology, grammar, semantics, and pragmatics.

Phonology

Phonology is the study of how speech sounds function to signal contrasts in meaning in a language. Our familiarity with English orthography tends to make us think of speech sounds as discrete and immutable segments: thus we learn that there are three sounds in ‘pat’, and the same three sounds occur in a different order in ‘apt’ and ‘tap’. Only when we study other languages do we learn that the way in which we classify speech sounds is not universal. For example, there are articulatory differences in how English speakers usually produce stop sounds (such as the ‘p’ sound), depending on whether the sound occurs as a single consonant (as in ‘pat’) or in a syllable-initial consonant cluster (as in ‘spat’). A stop preceding a vowel is usually produced with a puff of air (aspiration), except when in a cluster. However, in some languages (e.g. Thai and Hindi) the two variants of stop sounds (aspirated and unaspirated) can both occur at the start of words, but the meaning of the word will depend on which is used. Thus, for the speaker of Thai, there is just as much difference between an aspiratrd and unaspirated stop as there is for the Fnglish speaker between a pair of sounds such as /b/ and /p/. Conversely, English distinguishes between some sounds that are treated as a single sound in other languages. There is, for example, no distinction between /r/ and /I/ in Japanese.

Ladefoged (1975) defines phonemes as the smallest segments of sound that can be distinguished by their contrast within words. In English, ‘pat’ and ‘bat’, or ‘cap’ and ‘cab’ are different words: therefore we regard /p/ and /b/ as different phonemes. However, ‘pat’ is perceived as the same word, regardless of whether it is produced with an aspirated or unaspirated initial stop: therefore the aspirated and unaspirated forms of /p/ are treated as different versions of the same phoneme.

Note that the phoneme is an abstract unit, defined according to how sounds affect meaning, and not just in terms of acoustic and articulatory characteristics. Phonology, the study of sound patterns of language, may be contrasted with phonetics, which is concerned with articulatory and acoustic specification of speech sounds.

The phonemes used in the standard form of English spoken in Great Britain (known as Received Pronunciation) may be grouped into 24 consonant and 20 vowel sounds, as shown in Table 1.1. The main phonological difference between Received Pronunciation and other dialects and varieties of English is in the vowel system (see Hughes & Trudgill 1979 for an account of English dialects used within the UK, and Ladefoged 1975 for an introduction to American/British differences).

Table 1.1Phonetic symbols used for phonemes: Received Pronunciation

Consonants | Vowels |

/p/ as in pill | /i/ as in see |

/b/ as in bill | /ı/ as in s/t |

/t/ as in till | /ε/ as in set |

/d/ as in dill | /a/ as in sat |

/k/ as in kill | /  |

/g/ as in gall | /  |

/m/ as in men | /  |

/n/ as in net | /  |

/ŋ/ as in long | /u/ as in boot |

/f/ as in fail | /^/ as in duck |

/v/ as in veil | /З/ as in bird |

/θ/ as in think | /ə/ as in about |

ð/ as in though | /eı/ as in play |

/s/ as in sail |  |

/z/ as in zoo | /aı/ as in my |

/∫/ as in show |  |

/З/, y as in measure |  |

/t∫/ as in church | /ıə/ as in here |

/dЗ/ as in gem | /εə/ as in there |

/I/ as in line | /uə/ as in cruel |

/r/ as in right | |

/w/ as in will | |

/j/ as in yet | |

/h/ as in hat |

Early Studies of Articulatory Development

How do children learn the phonological system of their native tongue? Early studies in this field concentrated on motor proficiency in speech sound production. These studies documented which sounds were within a child’s repertoire at different ages. In English, for example, it was noted that plosives and nasals were among the first consonants to appear, with fricatives, affricates and clusters developing later. Table 1.2 shows the ages of acquisition given by Berry & Eisenson (1956) for different phonemes.

Table 1.2Age of articulatory efficiency of 22 consonant sounds (after Berry & Eisenson 1956)

Age | Sounds mastered |

by 3½ | b p m w h |

by 4½ | d t n g k ŋ j |

by 5½ | f |

by 6½ | v ð ∫ З l |

by 7½ | s z r θ |

These early studies did not pay much regard to how children used sounds meaningfully, their concern being principally with articulation. Whilst an articulation analysis classifies sounds produced by children according to whether the sound is phonetically accurate in terms of the adult system, a phonological analysis is concerned with how a child uses sounds to convey distinctions in meaning. To illustrate this point, consider three hypothetical children: Adam pronounces ‘cup’ as ‘tup’, ‘cake’ as ‘cake’, ‘take’ as ‘cake’, and ‘time’ as ‘time’. Ben pronounces all these words correctly. Both children can articulate [t] and [k], but Adam, unlike Ben, does not make a phonemic distinction between these sounds, so both ‘cake’ and ‘take’ are pronounced the same. A third child, Chris, uses the non-English sound [x] in some contexts where [k] would be expected: ‘cup’ is pronounced correctly, ‘cake’ is [xeix] and ‘take’ is [teix]. Chris would be identified as making articulatory errors on a classic articulatory analysis, and his speech would undoubtedly sound odd, but a phonological analysis would show that he does maintain a consistent distinction between sounds which correspond to different phonemes in English.

The Contribution of Jakobson

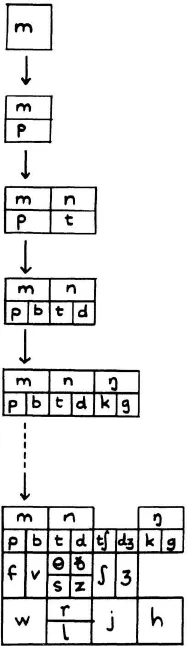

An important breakthrough in the conceptualization of development of speech sound production was Jakobson’s ‘Kindersprache, Aphasie, und allgemeine Lautgesetze’, published in 1941 and translated into English in 1968. Jakobson adopted a phonological framework, studying children’s language just as a linguist would approach a new foreign language. Thus he looked for regularities in the sounds and sound patterns used by young children, concentrating not on listing which sounds the child could produce, but on documenting which sounds the child treated as distinctive in signalling meaning. He concluded that children build up a repertoire of phonemes by a series of binary splits. First the child would make a broad distinction between consonants and vowels (but would not initially distinguish between sounds within either of these categories). Each of these classes would then be progressively subdivided: for example, a common pattern would be for consonants to be divided early on into nasal and non nasal, later divisions being based on contrasts corresponding to different places of articulation (lips, alveolar ridge, or velum). Jakobson’s theory likens phonological development to embryological development: an initial undifferentiated sound class subdivides into two: each of these subdivides further, this process being repeated until a fully differentiated system is arrived at (see Fig. 1.1).

Fig. 1.1Postulated stages in the development of a system of contrasts between English consonants

Later workers have questioned many of Jakobson’s conclusions, particularly insofar as he proposed that the order of acquisition of contrasts was consistent across different languages, and consistent for all children (e.g. Menn 1985). Nevertheless, his work remains an important influence, and has led to a fruitful line of investigation into development of speech sounds in children, moving away from phonetic error analysis to consider the phonological systems of young children.

Phonological Processes

Space prohibits a comprehensive review of theories and research in this area (see Grun-well 1982), and forces us to restrict consideration of later work to one particularly influential theory. This is Stampe’s (1969) proposal that children’s developing phonology should be described in terms of simplifying processes, affecting whole groups of sounds rather than single phonemes, and determined by ease of articulation For example, Stampe maintained that young English-speaking children can perceive the distinction between velar stops (/k/ and /g/) and alveolar stops /t/ and /d/), and their internal representations of words differing on this distinction would not be the same. However, because alveolar sounds are easier to produce, a process of ‘fronting’ operates, affecting velars as a class, so that ‘cup’ is pronounced as ‘tup’, and ‘girl’ as ‘dirl’. This is an example of a process which involves substituting one type of sound for another. Other processes involve the influence of one sound upon another within the same word. Thus there is a tendency to maintain the same place of articulation for successive segments, so that articulation of one consonant is affe...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Contributors

- Glossary

- 1. Language development in unexceptional circumstances

- 2. Extreme deprivation in early childhood

- 3. Hearing children of deaf parents

- 4. Bilingual language development in preschool children

- 5. Language development in twins

- 6. Intermittent conductive hearing loss and language development

- 7. Oral language acquisition in the prelinguistically deaf

- 8. The acquisition of syntax and space in young deaf signers

- 9. Visual handicap

- 10. Down’s syndrome

- 11. Dissociation between language and cognitive functions in Williams syndrome

- 12. Infantile autism

- 13. Language development after focal brain damage

- 14. Language development in children with abnormal structure or function of the speech apparatus

- 15. Five questions about language acquisition considered in the light of exceptional circumstances

- Appendix: A non-evaluative summary of assessment procedures

- References

- Author index

- Subject index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Language Development In Exceptional Circumstances by Dorothy Bishop,K. Mogford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Developmental Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.