- 162 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The literature on modernist and postmodernist urban development is abundant, yet few researchers have taken up the challenge of studying the areas hi which marginalized people live as sources of resistance to continued modernization. In Marginal Spaces, Michael Smith has assembled case studies combining structural and historical analyses of the moves of powerful social interests to dominate social space, and the tactics and strategies various marginalized social groups employ to reclaim dominated space for their own use. The marginal spaces embodied in the title of this fifth volume of the Comparative Urban and Community Research series include five sites of domination and resistance. A squatters' movement in Ann Arbor, Michigan, resists the adverse consequences of four decades of urban development. A homeless encampment in Chicago engages hi "guerilla architecture" and other moves designed to reconstitute prevailing social constructions of the problem of "homelessness." An antigentrification movement hi the East Village of New York engages hi an ongoing struggle to resist efforts by developers to market their neighborhood as space for luxury condominium development. There is a Public Housing Council organized by African American women hi New Orleans that is resisting both the material regulation of their daily lives and the dominant social construction of public housing as a racially gendered space suitable only for "dependent" women and children of color. Finally, there is a subordinate labor market niche hi California agriculture where indigenous Mixtec peasants from Oaxaca are displacing the more traditional mestizo farm workers, but who are also politically organizing as a transnational grassroots movement, pursuing a binational strategy to alleviate then- economic, political, and cultural marginality. Contributions and contributors include: "House People, Not Cars!" by Corey Dolgon, Michael Kline, and Laura Dresser; "Tranquillity City" by Tahnadge Wright; "Private Redevelopment and the Changing Forms of Displacement hi the East Village of New York" by Christopher Mele; "Resisting Racially Gendered Space" by Alma Young and Jyaphia Christos-Rodgers; and "Mixtecs and Mestizos hi California Agriculture" by Carol Zabin. This volume will be of interest to urban planners, sociologists, and political scientists, especially those with strong interests hi local ethnography and concrete policy.

Information

1

"House People, Not Cars!": Economic Development, Political Struggle, and Common Sense in a City of Intellect

Corey Dolgon, Michael Kline, and Laura Dresser1

For a mass of people to be led to think coherently and in the same coherent fashion about the real present world, is a "philosophical" event far more important and "original" than the discovery by some philosophical "genius" of a truth which remains the property of small groups of intellectuals.

—Antonio Gramset, Prison Notebooks

A little before eight-o'clock in the morning on October 6, 1990, the authors of this paper joined other members of the Homeless Action Committee (HAC) in blocking the entrances to a municipal parking lot behind Kline's department store in downtown Ann Arbor. HAC had chosen the parking lot as the site for a noontime rally to "Save Ann Arbor Homes," a reference to the squatted houses (originally opened up by HAC) adjacent to the lot and now threatened with demolition. A successful rally required that we prevent "business as usual" on a valuable parcel of downtown real estate. As it turned out, our blockade of the parking lot led to a confrontation with angry merchants who tried to have us removed by the police. But HAC successfully shut down the lot and the rally proceeded as planned.

Behind the clash between activists and merchants lay a struggle over four decades of development in Ann Arbor. As we will demonstrate, the conflict over the "Kline's lot" is embedded in both a historical analysis of the city's economic growth and political landscape since World War II as well as a specific approach to political activism and intellectual work committed to social struggle. What links activists, developers, and the university, we will argue, is a contest over the meanings and stakes of intellectual work and knowledge production in a city that sells itself as a successful example of how a "postindustrial" urban economy can work. Implicated in such a struggle are several levels of social contestation. Therefore, we begin by looking closely at the political economy of Ann Arbor, detailing the rise of the University of Michigan as an institution committed to scientific research as well as a corporation interested in seeking increased public and private funds to feed its own visions of growth. We continue by examining the creation of a pro-growth regime comprised of local political officials, the city's chamber of commerce, and university administrators whose interests converged in reshaping the city's image as the "Research Center of the Midwest." We will also note evolving tensions within this "ruling bloc" and the strategies employed to solve certain conflicts among business leaders, university officials, and politicians. And we will consider how major economic shifts affected changes in Ann Arbor's built environment causing a double movement of gentrification and displacement that had especially devastating effects on the city's historically black working-class communities.

The second section of this paper investigates how these same forces had a significant impact on the city's economic and political landscape, creating new forms of intense poverty (homelessness) and demanding innovative forms of political organizing. We examine questions of political resistance and mobilization, asking how a political action group, HAC, with few resources and no formal access to power can challenge a community's political and economic elites whose pro-growth ideology has become so embedded in the community's image of itself. In specific, the paper analyzes how HAC creates a complex, historically based, and politically committed common sense that not only counters pro-growth ideology, but challenges the very foundation of Ann Arbor's economic growth—the University of Michigan. By offering a more collective and liberatory sense of intellectual work, HAC undermines the legitimacy of the type of elite knowledge production that is either blatantly linked to the interests of capital and economic growth or naively framed by scholarly claims of neutrality or objectivity.

Building a City of Intellect: A History Pro-Growth Development and Displacement

Where once there was farmland, new kinds of seeds are planted in some of the hansomest, parklike, industrial acres of the country, and wealth is created out of less than thin air: the operation of the intellect, devoted to research. . . . The economic growth is self-feeding, self-sustaining, and progresses geometrically. [Ann Arbor] is one of the fastest growing U.S. cities, and the growth is highly selective, by choice of the individuals who planned the growth to be a kind most beneficial to the city, an industrial aristocracy of innovators.

—Ann Arbor Chamber of Commerce, 1970

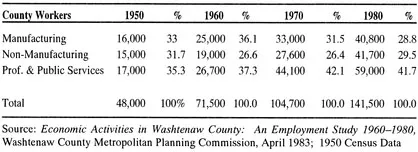

Between 1950 and 1990, Ann Arbor (the largest city in Washtenaw County and now the second largest city in Southeastern Michigan after Detroit) almost tripled in size to just over 110,000 people. The growing population was mostly employed in higher education and healthcare-related fields, technological research and development companies, assisting financial and informational service firms, and restaurants, coffee shops, and other businesses involved in producing an increasingly large and profitable gentrified leisure industry.2 An employment study of Washtenaw County's economic activities demonstrates an overwhelming growth in the total workforce as well as a rise in both the public and private service sector and a decrease in the proportion of total employment comprised by manufacturing jobs. These developments exemplified major trends in U.S. capital: the shift towards a service economy and the related rise of computer technology and informational service industries and a bifurcated labor force characterized by "an increased need for professionals and technicians with special training and expertise in restricted segments of the job market, a reduced number of traditional blue-collar jobs and a greater demand for part-time and low wage skilled service workers to perform very routine tasks."3

Ann Arbor's successful development as a "specialized service center" was partly due to its already existing "postindustrial" service based economic structure. As the previous table demonstrates, compared to a much lower national average, over one-third of Washtenaw County's workforce was employed in professional and public services as early as 1950. In Ann Arbor, the percentage of professionals and service-oriented jobs was even higher since the largest manufacturing sites belonging to Ford and General Motors were both located in the neighboring city of Ypsilanti. And most of Ann Arbor's jobs directly or indirectly related to the University of Michigan (one of the country's largest research universities) and the increasing number of R&D firms taking advantage of the school's proximity. Between 1945 and 1990 the U-M grew in enrollment by almost 150 percent to over 32,000 and increased its total revenues from $24 million to $1.6 billion. The largest growth in revenues occurred in the U-M's hospital (35 percent of the 1990 budget), private endowments (almost 14 percent of the 1990 budget as opposed to 3 percent of the 1950 budget), and federally sponsored programs (25 percent of the 1990 budget as opposed to less than 2 percent of the 1950 budget). Much of this federal money came from the Departments of Defense and Energy and went to the College of Engineering and other related programs for the purposes of military research. Numerous university projects established in the immediate postwar period courted both federal and corporate money which in turn fueled the U-M's institutional growth and restructuring that facilitated new production activities for an evolving, knowledge-based, global economy.4

Rising from the Ashes: The University of Michigan and the "New Capitalism"

Following World War II, college campuses across the United States experienced rapid growth. Stimulated by the G.I. Bill, an increasingly powerful cultural reliance on a highly credentialled professional-managerial class, and the government's new focus on universities as sites of scientific research, many universities expanded in size and underwent widespread administrative reorganization.5 At the University of Michigan, most of the organizational changes caused by restructuring occurred in the business and financial offices as a direct result of the school's burgeoning research functions and revenues. Federally funded research for military-related purposes at the college of engineering and national behavior studies rationalizing the rise of a middle-class technocracy conducted by the Institute for Social Research led to the purchase of large plots of land on the city's northside and the construction of tall office buildings in the Central Campus area. The number of administrators and office staff personnel charged with coordinating financial policies, procedures, priorities and transactions increased tenfold. Still, although many research projects were inextricably linked to Cold War-inspired military and cultural knowledge production, the UM made its most important institutional restructuring efforts around the possibility of attracting private sector research funds.6

The drive tor corporate research money actually began in 1948 when the U-M Board of Regents established the Michigan Memorial-Phoenix Project as a practical and "living" tribute to U-M men who had died in World War II The Phoenix Project, an atomic energy research center, would harness the same "resources, brain power, and initiative' that unleashed forces of mass destruction during the war, and convert them into 'peaceful purposes' for promoting the 'world's welfare.'" Predating President Eisenhower's 1953 "Atoms for Peace" program, the Phoenix campaign chairman, Chester Lang (a vice president of General Electric and U-M alumnus) explained that atomic energy research promised the "richest possible peacetime results" if linked to the same "free-enterprise system" that had brought our nation such "great progress in the past." In fact, U-M president, Alexander Ruthven, cautioned that if government maintained complete control over atomic energy research, the result could be a "policy of drifting" where the potential energy source of a "second industrial revolution" would be stymied by political bickering and ideological squabbles. Thus, unlike the many federally sponsored U-M research programs that began during and immediately after World War II, the Phoenix Project was privately financed, partially by individual contributions from wealthy alumni, but predominantly by large corporate donations raised during a successful $6.5 million fundraising campaign. Eventually, the drive for corporate research funding triggered by the Phoenix Project would represent one of the most important aspects of institutional restructuring at the University of Michigan: the creation of a Development Council.7

In 1951, members of the Phoenix Campaign's executive board met to discuss the possibility of making a private fundraising effort permanent. Touting a "New Partnership" and an "Institute for Regional Research" in science and engineering, the U-M was courting major contributions during the Phoenix Campaign by promising that support for academic research could turn big profits for the private sector. In forming a Development Council, Chester Lang, new U-M president, Harlan Hatcher, Phoenix Campaign Director, Alan McCarthy, and a local Ann Arbor financier and U-M alumnus, Earl Cress adopted the Phoenix Project's strategies of inviting major corporate leaders to be on the Council's board of directors as well as tailoring special presentations for specific companies to demonstrate how certain research projects might be applied by each targeted industry. Although the Council claimed that its goal was to survey and meet the "already existing needs" of the university, "from the outset, it [was] contemplated that a Corporation Program would be one of the more important facets of the University's development operation." The list of "obvious" reasons for such an approach included:

- The somewhat phenomenal success in realizing corporate support, both designated and undesignated, for the Phoenix project.

- The growing tendency on the part of corporate interests to support higher education within legal and tax limitations.

- The general encouragement the government and the courts have given in recent months to the authorization of contributions to education.

- Public announcements of business organizations advocating that colleges and universities deserve the broadest support of business enterprises.

- The current trend of corporate interests to establish contribution committees and/or corporate foundations to facilitate the allocation of grants for welfare or philanthropic purposes.8

Thus, while governmental legislation and court decisions made corporate sponsored research increasingly profitable (companies could make tax-deductable research grants to universities whose work would then be made available for industrial use) the U-M Development Council recognized the imminent explosion of corporate support for universities as sites of scientific research and knowledge production. The Council also realized that the U-M's own potential for growth beyond its "already existing needs" would rest with the institution's ability to take advantage of these corporate prospects. However, as early as 1954, competition with other major research universities was steep for, as one business columnist put it, "latching onto the corporate dollar has become a selling job in a buyer's market."9

Although the U-M's College of Engineering had participated in contract research with corporations for over thirty years, the postwar period marked a new phase where engineering faculty and administrators synchronized efforts with the Development Council to solicit increased corporate investments that equated knowledge production with economic growth and economic growth with national progress and the public good. The U-M's Engineering Research Institute 1951 report, which showed an increase in contract research from $100,000 in 1920 to about $250,000 in 1940 to almost $3.5 million in 1951, explained that the wide variety of achievements in pure science shared a common thread: "many . . . have already found technological applications, resulting in new and better work materials and products and in lower production costs; others will eventually lead to more technological advances, which we hope will improve our way of living."10 In 1952, the Industrial Participation Program (IPP) offered corporations three-year subscriptions to quarterly reports on university scientific and technological research for the sum of $15,000. In 1954, the U-M teamed with Ford Motor Company to build an advanced training center in engineering and business administration on the site of Henry Ford's old mansion in Dearborn, Michigan. Henry Ford, Jr. explained that his company was "especially concerned with the shortage of young scientists needed to maintain our country's progress.. . . [Funding the UM's Dearborn Center] offers us a practical means for expressing positively our belief in industry's responsibility to education." Meanwhile, another major target of the U-M's Development Council's efforts, General Motors, issued their new policies on funding higher educational programs claiming that "Material progress is the business of industry and intellectual development is the business of our institutions of higher learning. Both are indivisible aspects of our growth as a nation."11

Culminating this consensus that economic growth fueled by scientific knowledge production and facilitated by private investment in public institutions of higher education was in the public's interest, the U-M created an Institute for Scientific Research (LST) with a specific branch called the Industrial Development Division (IDD). In 1958, University officials lobbied Michigan state legislators to fund the creation of a research institute whose stated objective was to aid industrial growth. J.A Boyd, the IST's first director, explained that the Institute provided for "the direct state support of industry through a program of science and technology . . . recognizing that not only the economic growth of our state but also our survival as a nation is dependent upon a dynamic program in science and technology." By the late 1950s and early 1960s it had become clear that, although Michigan's industrial growth had benefitted from the postwar boom in the auto industry, these figures had begun to decline. Meanwhile, in accordance with the national defense needs and the growing technological demands of business and industry, the manufacture of electronics, aerospace equipment, chemical and petroleum products were becoming the most important growth industries in the country. In one of the IDD's first major reports comparing the research patterns of Michigan universities with state and national trends, U-M researchers explained that,

[Since] technological advance is fundamental to economic growth ... those geographical regions where univer...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgment

- Introduction: The Social Construction of Marginal Spaces

- 1 "House People, Not Cars!": Economic Development, Political Struggle, and Common Sense in a City of Intellect

- 2 Tranquility City: Self-Organization, Protest, and Collective Gains within a Chicago Homeless Encampment

- 3 Private Redevelopment and the Changing Forms of Displacement in the East Village of New York

- 4 Resisting Racially Gendered Space: The Women of the St. Thomas Resident Council, New Orleans

- 5 Mixtecs and Mestizos in California Agriculture: Ethnic Displacement and Hierarchy among Mexican Farm Workers

- Contributors

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Marginal Spaces by Michael Peter Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.