- 316 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Ice Age Earth provides the first detailed review of global environmental change in the Late Quaternary. Significant geological and climatic events are analysed within a review of glacial and periglacial history. The melting history of the last ice sheets reveals that complex, dynamic and catastrophic change occurred, change which affected the circulation of the atmosphere and oceans and the stability of the Earth's crust.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ice Age Earth by Alastair G. Dawson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Environmental Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this book is to describe evidence for fluctuations in the Earth's climate that took place during the Late Quaternary – a time interval corresponding approximately to the last 130,000 years. It attempts to provide an account of the most important geological and geomorphological changes that occurred as a result of global and regional changes in climate. It also endeavours to describe the patterns of climate change and explain why they took place.

The field evidence for past variations in the Earth's climate has been used by scientists interested in predicting future climates. In particular, it has enabled the development of advanced computer models of global climate change (general circulation models) in which past changes in global atmospheric and oceanic circulation have been numerically simulated. Recently, for example, studies of Antarctic ice cores have provided new information for the models on long-term variations of atmospheric CO2 and CH4 that can usefully inform discussion of modern global warming caused by Greenhouse gases. Similarly, recent reconstructions of environmental changes that took place during the melting of the last ice sheets have identified past periods of time when climate change took place extremely rapidly. This information is of great value in the study of modern global climate and its vulnerability to sudden changes. It is also of great value with regard to our ability to predict the regional impact of future climate changes.

The book opens with a review of past climate changes based on studies of ocean sediments and ice cores. Thereafter, a review is given of computer models of the general circulation of the Earth's atmosphere and oceans during the last ice age. This is accompanied by a comparative analysis of modern (interglacial) and ice age global circulation. Considerable attention is also given to the history of glaciation since the end of the last interglacial. Emphasis is placed on the regional variability in glacial history and the rapidity at which such changes appear to have taken place. A separate account is given on the melting history of the last ice sheets. This discussion also stresses the rapidity of past climate changes and the complexity of the environmental responses to widespread deglaciation.

A systematic account is given in later chapters of geomorphological changes that occurred in areas that were largely unaffected by glacier and ice sheet development. Thus the consideration of ice age periglacial environments discusses ways in which studies of Late Quaternary periglacial phenomena have contributed to our understanding of past climate changes. Similarly, a discussion is given on the information that studies of lakes, bogs and mires have provided on Late Quaternary climate variations. An account is also given on the evolution of Late Quaternary rivers as well as the response of aeolian activity to past climate fluctuations. There is also a discussion of the importance of volcanic ash layers in the dating of Late Quaternary sediments and a consideration of possible relationships between the largest volcanic eruptions of the Late Quaternary and periods of widespread global cooling. The nature of Late Quaternary crustal movements is also described and there is a detailed consideration of past sea level changes.

In the final chapter, there is an introductory description of Milankovitch insolation theory together with an account of reconstructed patterns of Late Quaternary Milankovitch insolation variations. The different types of geological evidence for past climate changes are summarised in this chapter and consideration is given to possible relationships between past climate changes, based on geological evidence, and Milankovitch insolation variations.

Any discussion of the timing and duration of Late Quaternary global climate change must risk stepping through a minefield of controversy. Of course, the reconstruction of past climate changes is dependent upon the application of reliable dating techniques and an understanding of the limitations of these methods. It should be stressed that this book does not consider these aspects of palaeoenvironmental reconstruction since there are already many other excellent textbooks that consider these subjects (e.g. Lowe and Walker 1984; Bradley 1985). Throughout the book, a conscious attempt has been made to use published ages for particular environmental changes that are considered the most reliable. For simplicity and ease of reading, standard error ranges for individual dates are omitted and the reader is referred to the published papers for this information. It is also assumed that the conventional radiocarbon timescale does not depart markedly from that based on sidereal years.

The information provided in the following chapters demonstrates that studies of Quaternary palaeoenvironments are highly interdisciplinary in character but there is still a great need for scientific specialists to be aware of the broader context of their research. Bradley (1985) has pointed out the danger and the challenge inherent in such developments. He argued that the danger is that in the future there will be limited interdisciplinary understanding and collaboration. He stated that the challenge is to avoid this pitfall and to develop an awareness of the advances of the various methodological developments that are being made. To that must be added the need to learn more about the past climate and environmental changes themselves. It is hoped that this book may contribute something towards this goal.

TIMESCALES AND TERMINOLOGY

General time subdivisions

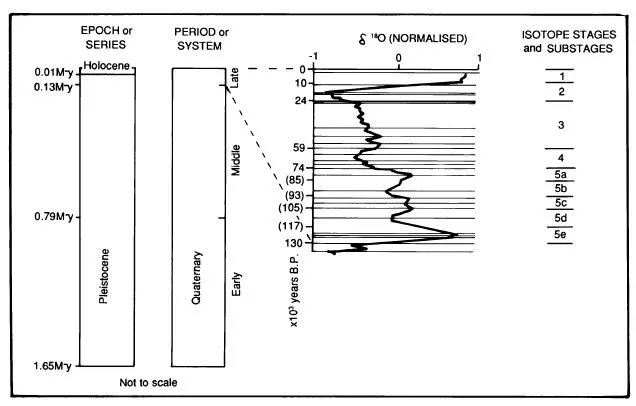

The Quaternary period, the later part of which is discussed in this book, is often subdivided into two epochs or series – the Pleistocene and Holocene. The Quaternary period is often subdivided into sections – Early, Middle and Late. The boundary between the Early and Middle Quaternary is usually defined by the Matuyama-Brunhes geomagnetic polarity reversal, considered here to have occurred near 790,000 BP (Johnson 1982). The boundary between the Middle and Late Quaternary is regarded as equivalent to the beginning of oxygen isotope substage 5e that represents the warmest phase of the last interglacial. Here, the age of this boundary defined from marine oxygen isotope stratigraphy is considered to be 130,000 BP (Martinson et al. 1987) (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The Late Martinson Generalised time subdivisions of the Quaternary period (after Goudie 1983). Quaternary is additionally subdivided into oxygen isotope stages (after et al. 19871.

Time subdivisions of the Late Quaternary

In most parts of the world, the time interval between the start of oxygen isotope substage 5e (130,000 BP) and 10,000 BP is assigned a formal chronostrati-graphic name1 (e.g. Weichselian: NW Europe; Devensian: British Isles; Wurm: central Europe; Valdai: European USSR; Wisconsin: North America). With the exception of the chronostratigraphic subdivisions for the USA and Canada, these time intervals are subdivided into three and accorded the prefixes Early, Middle and Late (e.g. Early, Middle and Late Weichselian). In recent years, these time subdivisions have been linked to the marine oxygen isotope chronology and this has been used to assign age ranges to the respective time intervals (Figure 1.1). For example, in Scandinavia the Early Weichselian is considered to represent the time interval between marine oxygen isotope substages 5d and 5a, the Middle Weichselian to isotope stages 4 and 3 and the Late Weischselian to isotope stage 2. The boundary between the Pleistocene and Holocene (isotope stage 1) is arbitrary but is generally regarded as having occurred near 10,000 BP. Discussion of environmental changes that took place during the present (Holocene) interglacial is here confined to the Early Holocene – ending at approximately 7,000 BP. This time was chosen since it coincides broadly with the final disappearance of the remnants of the last great ice sheets in the northern hemisphere and the return of most glacial meltwater into the world's oceans. It also coincides approximately with the beginning of significant human impact on the environment and the reader is referred to Roberts (1989) for a more complete discussion of Holocene environmental changes that took place after 7,000 BP. For convenience therefore, the term Late Quaternary is not used in the text in its strictest sense since it does not consider environmental changes that took place after circa 7,000 BP.

Oxygen isotope chronology

A study of the various academic papers on Late Quaternary environmental changes will leave the reader very confused about the ages of the respective stages and substages outlined in oxygen isotope stratigraphy. Recently, a revision of the most accurate stage and substage ages has been undertaken by Martinson et al. (1987) (Figure 1.1). This was accomplished by comparing the oxygen isotope chronology based on studies of deep sea sediments (see Chapter 2) with the pattern of variations in the Earth's orbit geometry according to Milankovitch theory (see Chapter 13). Martinson et al. (1987) used this concept of 'orbital tuning' to develop a high-resolution timescale for the Late Quaternary. Owing to its relatively recent publication, the oxygen isotope chronology used by Martinson et al. (1987) does not coincide with the age intervals for the Late Quaternary that are presently used in the USA and Canada. Furthermore, the age subdivisions that are used in Canada and the USA also differ from each other (see Table 4.1).

NOTES

1 Chronostratigraphy is one of several categories of stratigraphic subdivision. It refers to the classification of stratigraphic units according to age. Other categories are lithostratigraphy (the classification of local sediment units or rock successions according to changes in lithology), biostratigraphy (classification of sediment units according to variations in fossil content) and morphostratigraphy (the classification of landforms according to their relative ages) (see Lowe and Walker 1984).

2

OCEAN SEDIMENTS AND ICE CORES

OXYGEN ISOTOPE VARIATIONS IN OCEAN SEDIMENTS

Our understanding of Quaternary climate changes has been revolutionised by the study of sediments that have accumulated on the floors of the world's oceans. This is because ocean floor sediments generally provide a continuous record of sedimentation and only on rare occasions have they been disturbed by episodes of erosion. Such exceptions occur in areas where submarine landsliding and turbidity current activity have taken place. Sediments over much of the ocean floor consist predominantly of the skeletal remains of deposited calcareous and siliceous micro-organisms that have settled out of the water column. Most calcareous tests are dissolved below about 4 km water depth (the calcite compensation depth (CCD)) due to dissolution in the undersaturated water (Bradley 1985). As a result, most ocean cores used in palaeoenvironmental studies are taken from water depths shallower than approximately 4 km. Investigations of the undissolved species present within ocean sediment cores may therefore be used to reconstruct former patterns of environmental change.

Evidence of the former marine conditions under which the calcareous micro-organisms lived can be determined by the analysis of the stable isotope ratios of the oxygen in the carbonate skeletal remains. Thus the relative abundance of the oxygen isotopes in the tests of calcareous micro-organisms can be related to the abundance of these isotopes in the ocean water at the time the carbonates were produced. In this respect, the calcareous microfossils from ocean sediments that have been most commonly employed in oxygen isotope analysis are those of protozoans known as foraminifera. Planktonic foraminifera have provided valuable information on former ocean surface conditions while benthonic species have provided information on former deep water ocean environments.

Modern oxygen isotope variations

The stable oxygen isotope composition of the carbonates produced by the micro-organisms and finally deposited upon death on the ocean floor is partly a function of the isotopic composition of the ocean water during the life span of the

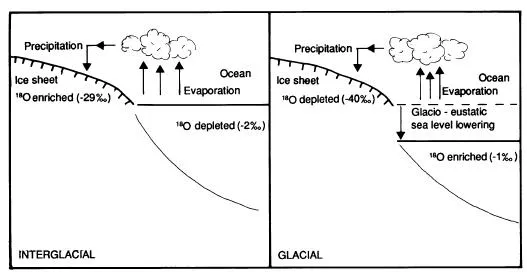

Figure 2.1 Schematic diagram showing in relative terms the respective enrichments and depletions of oxygen isotopes 16 and 18 during glacial and interglacial ages. The oxygen isotope curves for both ice cores and ocean cores are normally measured as 18O variations calculated with reference to the standard isotopic value of the PDB-1 reference belemnite from the Cretaceous Pee Dee Formation of South Carolina. Typical values of 18O for glacial and interglacial ages are shown as values per millilitre. Note that the measured 18O values for marine foraminifera are very small.

micro-organism and also of the temperature of the water in which the foraminifera lived. During the evaporation of sea water the different isotopes of oxygen in water molecules (16O, 17O and 18O) are released into the atmosphere by a process known as isotopic fractionation (Figure 2.1). The process is based on the fact that since the rate of water evaporation varies according to the density (and hence atomic weight) of the respective oxygen isotopes, there is a preferential evaporation of the lighter oxygen isotopes. Changes in the isotopic composition of sea water are mostly dependent on variations in 18O: in general 16O is passive in the cycle of isotope transfer. Oxygen isotope ratios of foraminifera carbonate are also influenced greatly by the water depth and the temperature of t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- A Volume in the Routledge Physical Environment Series

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of plates

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 INTRODUCTION

- 2 OCEAN SEDIMENTS AND ICE CORES

- 3 ICE AGE PALAEOCLIMATES AND COMPUTER SIMULATIONS

- 4 GLACIATION HISTORY FROM THE LAST INTERGLACIAL TO THE LAST GLACIAL MAXIMUM

- 5 THE MELTING OF THE LAST GREAT ICE SHEETS

- 6 ICE AGE PERIGLACIAL ENVIRONMENTS

- 7 LAKES, BOGS AND MIRES

- 8 RIVERS

- 9 ICE AGE AEOLIAN ACTIVITY

- 10 LATE QUATERNARY VOLCANIC ACTIVITY

- 11 CRUSTAL AND SUBCRUSTAL EFFECTS

- 12 LATE QUATERNARY SEA LEVEL CHANGES

- 13 MILANKOVITCH CYCLES AND LATE QUATERNARY CLIMATE CHANGE

- References

- Index