![]()

Adaptive Urban Health Justice

Of Machines and Butterflies

In planning, policy-making and public health, scientific metaphors shape much of how we interpret and intervene in the world. Policy science and management often tacitly view challenges like urban health much like a machine; if something seems to be broken the best approach is to take it apart, understand how all the parts work, fix each one, and put it back together. Public health often aims to emulate Western medicine where curing the body can also be like machine repair and focused on individual parts not the complex whole. In policy science as machine, the internal workings take priority since less is known about how to control the entire system and the ambient environment that might be influencing the machine's functioning. Not everyone can repair or even understand the workings of the policy-making machine, so the theory goes, and only specially trained experts are trusted to participate.

Planning for health equity in cities, as I will argue in this chapter, confronts many of the core assumptions of the machine metaphor. Cities have many unpredictable parts, are variegated and the sum of their parts rarely equate easily with the functioning of the whole. People in cities find ways to interpret and assign meaning to places in surprising and unexpected ways, even when certain aspects of the city are ‘hard-wired’ for a particular function, such as roads and parks. Cities are constantly built and rebuilt socially, physically and interpretively. The interpretations and possibilities of cities are influenced by forces from within their neighbourhoods and municipal boundaries, but also by policies and institutions outside at the national and international scales. With all this complexity, the rational machine-like approach to policy change and management has proved inadequate.

This chapter argues that cities are complex systems characterized more by uncertainty, indeterminacy and ignorance than certainty, functions and rationality (Batty, 2008; Tsoukas, 2005). A complex system must develop processes of adapting to change, since it is near impossible to model and predict the future of complex systems. This concept is the driving idea behind adaptive urban health justice.

In complex systems small, localized events can have an unexpectedly large influence on the entire system. In chaos theory, this is known as the butterfly effect, first coined by Edward Lorenz. Lorenz postulated that in the complex and uncertain meteorology system, a butterfly flapping its wings in the Amazon today can affect the formation of a hurricane thousands of kilometres away in the near future. The butterfly can have this impact if the initial conditions when the wings are flapped are sensitive to the small movement.

So, in complex cities, we might image our butterflies as neighbourhood actions working in unpredictable ways to radically alter not just the city, but an entire metropolitan region. Healthy city planning is about creating the enabling conditions for the butterflies to take flight and preparing to learn from and adapt to the unpredictable impacts that may result. Yet, healthy city planning is not agnostic about the existing conditions that currently do or do not exist in cities that might enable butterflies; identifiable policies, institutions, social movements, cultural practices, ideologies and so on have helped shape inequities that plague cities today, and deliberate changes to these same forces are necessary to enable healthy and equitable city planning.

To make this abstract discussion more concrete, this chapter turns to existing frameworks to offer more details of the processes and practices that must underwrite adaptive urban health justice. The existing frameworks include eco-social epidemiology (Krieger, 2011), sustainability science as framed by science and technology studies (Kates et al., 2001; Gibbons et al., 1994) and adaptive ecosystem management (Norton, 2005; NRC, 1999).

Eco-Social Epidemiology

The first concept that helps link the complexity of cities and urban systems with public action for health equity is eco-social epidemiology. First articulated by Nancy Krieger in 1994, eco-social epidemiology explicitly asks ‘who and what drives current and changing patterns of social inequalities in health?’ (Krieger, 2011, p. 213). Thus, the starting point for urban adaptive health justice is inquiry into and a commitment to address social injustices. Eco-social epidemiology is an important framework for urban policy-making because it seeks to understand what explains the distribution of morbidity and mortality over time and place. This is different from asking what might cause a specific disease, a point I will return to later in this chapter.1 As Krieger (2011) has described, eco-social epidemiology has four core constructs that together direct inquiry and action.

Embodiment

The first concept of eco-social epidemiology is embodiment, which suggests that ‘we literally embody, biologically, our lived experience’, particularly the material and social worlds in which we live ‘thereby creating population patterns of health and disease’ (Ibid., p. 215). Thus, the foundation of understanding and acting to reverse health inequities is knowing the histories of people, groups, places and the social, political and economic decisions that over time have shaped these histories. Embodiment is not a static concept but rather a dynamic on-going event, much like our complex urban system. For instance, eco-social embodiment emphasizes the constant interactions between genes and ever changing social environments – the expression of genes rather than just the presence of a particular genetic sequence. As Krieger emphasizes, embodiment is a verb for ‘our bodily engagement (soma and psyche combined) individually and collectively, with the biophysical world and each other’ (Ibid., p. 222). People and the world they help shape are always active participants not passive subjects, in the processes of embodiment.

Embodiment can link epidemiology to city planning in currently under-hypothesized ways. City planning activities regularly shape the physical, cultural and social worlds of urban dwellers, but the field has not engaged with the bodily implications of its practices as much as fields like sociology and anthropology (Bourdieu, 1990; Emirbayer, 1997; Burawoy, 1998). Krieger explains the far-reaching intentions of eco-social embodiment and potential for linking currently disparate disciplines, describing it as:

A useful bridge to novel twenty-first century research in the cognitive and neurosciences, which are providing new evidence on the centrality of bodily sensory-motor experiences and interactions (with both organisms and the broader biophysical context) to the development and expressions of both cognition and behavior. Thus, embodiment conceptually stands as a deliberate corrective to dominant disembodied and decontextualized accounts of ‘genes’, behaviors and mechanisms of disease causation, offering in their place an integrated approach to analyzing the multilevel processes, from societal and ecological to subcellular, that co-produce population distributions of health, disease and well-being. (Krieger, 2011, p. 222)

Thus, for adaptive urban health justice, understanding history and context must be the starting points for exploring the relational interactions between society and biology.

Multiple Pathways of Embodiment

The second construct of eco-social epidemiology builds on the first and emphasizes that there are always multiple pathways of embodiment. To o often in public health and medicine we look for the ‘one big cause’ that can explain illness or promote wellbeing, such as sugar, dietary fats, smoking or physical activity (Taubes, 2008; Freedman, 2010). Public health also tends to model just one exposure at one point in time, often discounting multiple exposure pathways that change over one's lifetime. Eco-social epidemiology posits that multiple exposures happen at a range of scales, from the individual to the city/region to the global, and can include such pathogens as social and economic deprivation, environmental pollutants and toxins, discrimination and other trauma, targeted marketing of harmful commodities, inadequate health care and the degradation of life-supporting ecosystems (Krieger, 2011, p. 214). Here again city planners must understand how urban policies, institutions and practices shape and influence these factors, such as policies promoting racial residential segregation, taxation and government spending, infrastructure, transport and environmental policies and inclusive or exclusive decision-making processes.

Weathering Hypothesis

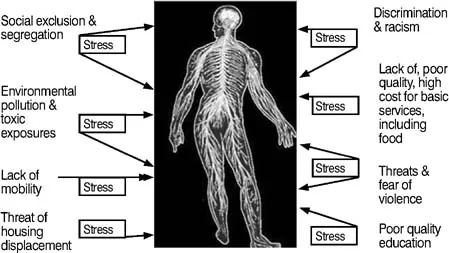

One hypothesis that can help city planners understand the bodily impact of multiple social, economic and other stressful exposures is called ‘weathering’ (Geronimus, 1992). The weathering hypothesis states that stressors on the body from social, economic, political and environmental deprivation and pathogens, from in utero throughout the life course, constantly wear down or weather the immune and neurologic systems leading to a range of diseases and possibly premature death (Ibid.). The hypothesis draws on a century of research into the effects of racism on health, from W.E.B. Du Bois and Kelly Miller in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries through studies by Frantz Fanon in the 1960s to twenty-first century articulations of structural racism (Du Bois, 1906; Fanon, 1968; Kelly, 1897; Williams, 1999). The idea of ‘weathering on the body’ is like the weathering sea salt air might do to the paint on the exterior of a building – a constant wearing away that reduces the paint's ability to protect the surfaces underneath and ultimately the inhabitants of the building. However, human weathering is not on the surface but to the human body's neuroendocrine system which reacts to socially produced, unnatural, stressors such as chronic unemployment, poverty, housing instability, lack of medical care, and the fear of crime (McEwen, 2000) (figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Cumulative social stressors on the human body. (Source: Author)

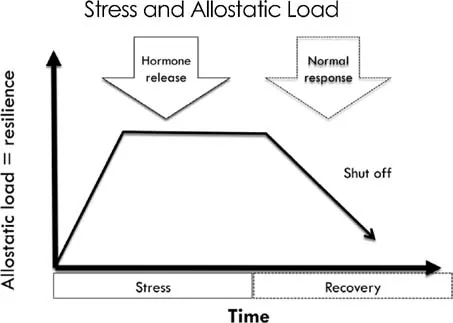

Under ‘normal’ stressful situations, the human body has a range of physical and chemical responses but primarily epinephrine (adrenaline) and cortisol are released to bring the endocrine and immune systems back to homeostasis. This adaptation is the body's ability to maintain stability under change and has been called allostasis (Ibid.) (figure 1.2). The weathering hypothesis states that under constant stressors the ‘allostic load’ continues to increase and the chemical release of ‘fight or flight’ hormones does

Figure 1.2 Normal biologic response to stress. (Source: Author, adopted from Geronimus, 1992)

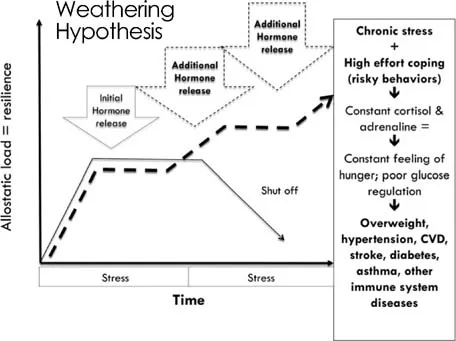

not properly regulate or shut-off. The hypothesis states that increased allostatic load wears away at the immune system as it overworks to manage the hormonal releases and attempt to return to homeostasis. In addition, the weathering hypothesis suggests that the over-secretion of cortisol and adrenaline can trigger other biologic responses like poor glucose regulation and constant feelings of hunger that can contribute to chronic diseases such as overweight and obesity, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, stroke, asthma and other immune-related illnesses (figure 1.3). While the weathering hypothesis was developed initially to explain poor birth outcomes for African-American women, there is reason to believe that the hypothesis can help guide city planners and others interested in understanding and addressing socio-economic inequities in health. Consistent with eco-social epidemiology, the weathering hypothesis demands that adaptive urban health justice identifies and articulates the institutional practices, routines and policies that are likely contributing to, mitigating or working to eliminate social stressors on a city's most vulnerable populations and places before rushing to offer ameliorative interventions.

Relational Framing: Exposure, Susceptibility and Resilience

The third core construct in eco-social epidemiology is that there is constant ‘interplay between exposure, susceptibility and resistance, at multiple levels (individual, neighbourhood, regional or political jurisdiction, national, inter- or supra-national) and

Figure 1.3 Weathering: constant biologic wearing from stressors & related morbidity. (Source: Author adopted from Geronimus, 1992)

in multiple domains (e.g. home, work, school, other public settings)’ (Krieger 2011, pp. 222–223). What this means is that healthy city planners cannot be content with only studying morbidity and mortality but must also take seriously the institutional and individual forces that promote resilience and decrease susceptibility to illness for people in particular urban plac...