1 Introduction

This chapter is designed to help you to think critically about the concept of justice and what it means in different contexts and communities and at different points in history. A key aim is to situate criminal justice among a range of strategies that might be (and are) employed when social harms, such as crimes, occur. Political and popular debates around ‘justice’ tend to be driven by the equitable (or otherwise) nature of adjudication and the processing of individuals through the criminal courts. As a result, they are, in the main, concerned with how to ‘hold offenders to account’. The chapter interrogates such common-sense understandings by exploring some of the defining features of criminal justice and uncovering the consequences of criminal justice being given priority in the resolution of disputes. The particular focus of criminal justice, as a set of procedures and regulations specific to individual nation states, is also exposed in consideration of the growing impact of international legal conventions, the emergence of transnational agencies of surveillance and the global flow of particular penal and crime control discourses and policies. Such developments necessitate moving beyond dominant understandings of ‘justice’ and ‘criminal justice’.

Section 2 of the chapter considers various ways in which the concept of ‘justice’ can be imagined and put into practice. Criminal justice represents a particular, but no means universal, method of responding to harms, conflicts and troubles. Section 3 examines some of the key characteristics and governing rationales for criminal justice – whether expressed as retribution, due process, crime control or rehabilitation – while Section 4 examines some of the ‘injustices’ that appear to be built into such procedures and rationales. Indeed, arguably we can learn more about the nature of criminal justice by examining its recurrent ‘tensions’ and ‘failures’ than by simply recalling its competing rationales. Section 5 further illustrates the shifting debates over what constitutes ‘justice’ by moving beyond nation state-specific prescriptions and examining how international cooperation and global relationships also impact on understandings of justice and on how (and by whom) justice might be delivered.

The aims of this chapter are to explore:

- the relationship between crime control and criminal justice

- the relationship between criminal justice and other means of delivering ‘justice’

- competing rationales for criminal justice based on due process, crime control, deterrence, retribution, incapacitation and rehabilitation

- the degree to which systems of criminal justice may also be major sources of injustice and a significant agency in the creation of further conflict, harm and dispute

- the impact that the emergence of supranational legal orders and international standards is likely to have on questions of national sovereignty and the democratic accountability of the nation state.

2 The constitution of ‘justice’

The concept of justice defies any straightforward definition. It often appears as abstract and opaque and can mean different things to different people. Yet it is frequently evoked as a social value that nation states strive to demonstrate and individuals demand.

Activity 1.1

Think about how you would define ‘justice’ in relation to the problems of crime in your local area or in society at large. Is the criminal justice system always the most effective means of responding to these problems?

Comment

When considering a definition of justice in relation to problems of crime, it is tempting to think first about high-profile (violent) or highly visible (vandalism, graffiti) crimes and the difficulties criminal justice systems have in combating and preventing these. Indeed, this is one of the limitations of reacting to crime after it has occurred – it is rarely an effective crime prevention tool. Further, the ability of the criminal justice system to respond and to deliver justice when a crime occurs can be heavily constrained by the procedural and structural form of the justice system itself. The relationship between crime and justice is sometimes tangential at best, as subsequent sections of this chapter will illustrate. How criminal justice is constituted depends on how crime is constituted. What is defined as a ‘crime’ dictates, to some extent, how justice will be pursued, and vice versa. However, what if justice were to be imagined outside of the limitations of a crime control or a crime prevention model? Can you think of some ways in which justice might be constituted if it were not constrained by formal criminal justice procedures?

The concept of justice can conjure up a multitude of competing images of fairness, equality, human rights, just deserts, deserved punishment, moral worth, personal liberty, social obligation and public protection.

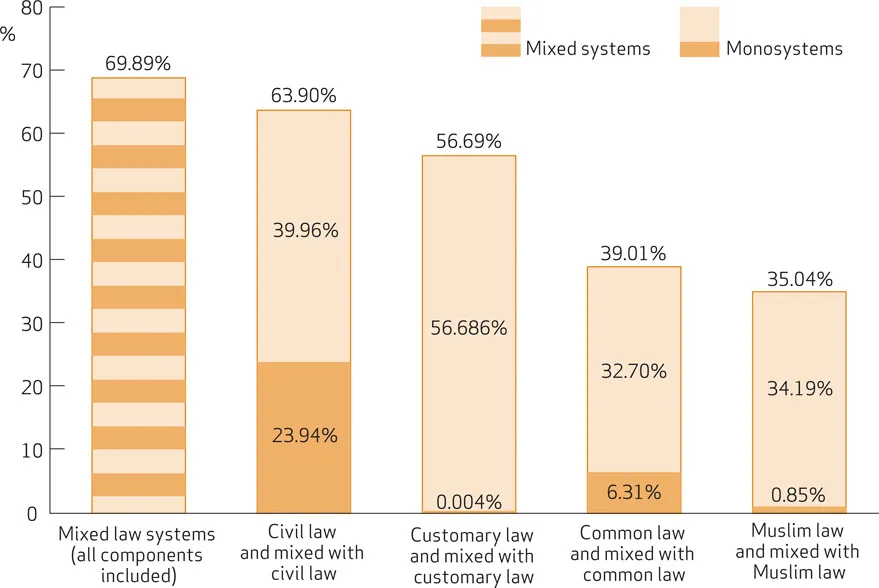

Figure 1.1 Distribution of the world population (%) per legal system (Source: www.juriglobe.ca/eng/syst-demo/graph.php)

It has been the subject of continual philosophical debate: is justice universal, derived from fundamental natural or divine principles, or is it invariably tied to specific (and changing) social and political conditions or to particular legal systems?

There is considerable variation between legal systems in the way in which criminal justice is constituted. Figure 1.1 identifies the percentages of the world population that are governed by the different legal systems in use throughout the world.

Mixed legal systems are the most prevalent. They are made up of some combination of civil, common, customary and/or Muslim law.

Very few jurisdictions operate a legal system that is wholly customary. A customary system of law is based on local knowledge, custom and cultural traditions, such as in Jersey and Andorra. The countries that operate customary law systems most often do so within a mixed legal system, combining, for example, customary law and common law principles. However, customary laws may still play a significant role in the adjudication of justice. Similarly, very few countries have legal systems that are influenced wholly by the religious beliefs of the region; the most ‘undiluted’ religiously based legal systems are those in some Islamic countries where Muslim law systems are guided by Sharia law.

Sharia law is the authority not just on legal matters alone: its rules and regulations also inform many aspects of day-to-day private and public life. But, again, most countries that operate Muslim law systems do so within a mixed system.

Many countries operate legal systems that are wholly civil- or common-law based. For example, most European countries, a large proportion of Asia and most of Central and South America operate civil law systems. Common law systems, by contrast, are found in the UK, the USA, Canada and Oceania. The main distinction to be drawn between common and civil law systems is that common law is principally guided by the courts, which set precedents for the law through rulings on specific cases. In common law procedures responsibility lies with defendants (and their solicitors) and prosecutors to present evidence and to prove their respective cases. The judge holds the responsibility of deciding which case has been presented most convincingly. In a common law system the law can be developed on a case-by-case basis. Civil law systems, by contrast, are inspired by Roman law and operate on codes of law – often established by legal scholars – which then guide judges on how to rule on specific cases. That is, judges in a civil law system have the responsibility of ensuring a just outcome of a case. They act as active investigators during legal proceedings and are thus able to pursue evidentiary lines of questioning with witnesses during the course of a case. Judges are not reliant on solicitors’ abilities to prove their respective cases and are often required to guide the proceedings. In addition, the appointment of judges differs between common and civil law systems. In common law systems judges are appointed or elected from the pool of practising solicitors, whereas in civil law systems judges are appointed or elected according to their professional judicial status.

Some countries have a mixed system of law that is nevertheless still heavily based in one system or another. The legal system in Scotland, for example, although a mixed system, retains a high degree of Roman or civil law. The rest of the UK, as mentioned above, and most of the countries that Britain colonised operate a common law legal system.

These differences in legal systems have a direct influence on how justice is constituted and delivered and, arguably, on how it is viewed and defined by the general public. Although this book considers global influences on justice, many of the cases considered in the chapters derive from common law systems. Making this distinction provides a main reference point from which to consider and interrogate various definitions of justice from around the world.

Beliefs about ‘what is just’ are often contingent on particular circumstances and may shift according to different cultural values and norms. As the following examples suggest, public and political perceptions of justice in the law are susceptible to changing sensibilities in relation to the demands of society, on the one hand, and the rights of individuals, on the other. In addition, the authority of the state can be reinforced or undermined by the public’s perception of its ability to uphold and deliver justice effectively.

Figure 1.2 Prometheus cartoon from 2007

Activity 1.2

First, read Extract 1.1 and consider the following questions as you do so:

- What might be some of the consequences of repealing laws that protect the rights of accused persons?

- Are there alternative ways in which justice might have been served for Julie?

- How can the rights of victims be protected while at the same time ensuring that the rights of the accused are also recognised and carefully guarded?

Extract 1.1

‘Justice for Julie’ campaign

Julie Hogg, a pizza delivery girl and mother of a three-year-old boy, went missing from her home in Billingham, Stockton-on-Tees, in November 1989, sparking an extensive police hunt.

The body of the 22-year-old was eventually found by Mrs Ming [Julie’s mother] during the following February, hidden behind a bath panel, when the keys to her daughter’s flat were returned to her.

Billy Dunlop, with whom Julie had previously had a relationship, was charged with her murder but acquitted after a trial. Nine years later he confessed to the crime and was jailed for perjury.

But he was not jailed for her murder because according to the law of double jeopardy as it stood, dating back 800 years to the Middle Ages, Dunlop could not be tried twice for the killing.

It ruled that a person acquitted by a jury could not be tried again on the same charge, not even if new evidence came to light.

Mrs Ming, 61, from Norton, Stockton-on-Tees who worked as a nurse at Middlesbrough General Hospital, fought for more than 15 years to change the law on double jeopardy and launched the Justice for Julie campaign.

Finally, in April 2005, the rule was altered under the 2003 Criminal Justice Act.

Dunlop, who was jailed for life after pleading guilty at the Old Bailey last September, became the first killer to be convicted under the new legislation.

Source: BBC News, 2007

Next, read Extract 1.2 and consider these questions:

- Can there be any ‘universals’ of justice: that is, principles or ideas that are internationally agreed, acknowledged and acted on?

- Is criminal law always the most effective means for resolving disputes and achieving ‘justice’? What other means might be employed?

- Can ‘justice’ ever be settled? Or is it by its very nature something that will be continually contested, struggled over and disputed?

Extract 1.2

‘Justice for Darfur’ campaign

Sudan should arrest war crimes suspects now

One year after the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued arrest warrants for two war crimes suspects in Darfur, human rights organisations around the world launched a ‘Justice for Darfur’ campaign, calling for the two to be arrested.

The organisations behind the campaign, including Amnesty International, Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies, Coalition for the International Criminal Court, Human Rights First, Human Rights Watch, and Sudan Organization Against Torture, have joined forces to call on the United Nations Security Council, regional organisations and individual governments to press Sudan to cooperate with the ICC.

The ICC has been investigating crimes in the region following a decision three years ago by the UN Security Council to refer to it the situation in Darfur. One year ago – on April 27, 2007 – the ICC issued two arrest warrants against Sudan’s former State Minister of the Interior Ahmad Harun and Janjaweed leader Ali Kushayb for 51 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity. Today the two men – who face charges of persecution, rape, and killing of civilians in four West Darfur villages – remain at large.

…

The Sudanese government has publicly and repeatedly refused to surrender either Ali Kushayb or Ahmad Harun to the Court. Instead, Ahmad Harun has been promoted to State Minister for Humanitarian Affairs, responsible for the welfare of the very victims of his alleged crimes. As well as having considerable power over humanitarian operations, he is responsible for liaison with the international peacekeeping force (UNAMID) tasked with protecting civilians against such crimes. The other suspect, Ali Kushayb, was in custody in Sudan on other charges at the time the ICC warrants were issued, but in October [2007] the government announced he had been released, reportedly due to ‘lack of evidence.’

…

[The ‘Justice for Darfur’ campaign organisers called on states and regional organisations, including] the European Union, a strong supporter of the Court and key player in bringing the Darfur crimes to the ICC Prosecutor, to press Sudan to cooperate with the ICC and comply with the warrants.

Source: Amnesty International Australia, 2008

Comment

The articles in Extracts 1.1 and 1.2 illustrate that individual and collective pursuits of justice ca...