![]()

Germany and the Burden of History

Summary

Germany is a country where history looms larger than it does in most other places. This chapter sets the scene for the book as a whole by linking Germany’s pre-1945 past with its contemporary politics. It begins by discussing the development of Germany from its beginnings as a Kulturnation (‘cultural nation’) through to the end of the Second World War. It then examines how post-war German politicians dealt with the legacy of this tumultuous history. Originally, they made little attempt to engage actively with Germany’s past, and it was only from the 1960s onwards that Germans really began to work through their country’s difficult heritage. By the mid-1980s, debates about how Germany’s history should be understood became much more mainstream. Unification in 1990 nonetheless complicated matters by introducing another dimension to the debate, that of how best to understand and interpret the history of the German Democratic Republic (GDR). The chapter concludes by highlighting why an appreciation of German history is vitally important if contemporary political life in the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) is to be understood adequately.

Introduction

Even the most cursory of glances at the way in which Germany functions will reveal that the burden of history has been very significant in shaping the contemporary political system. Many historians have traditionally debated issues concerning Germany’s role in the world, position at the heart of Europe, and difficulty in feeling at ease with itself by highlighting what is frequently known as the ‘German Question’ (Wolff, 2003). This question, or set of questions, revolves very much around where the German state should be geographically located (the lack of ‘natural’ frontiers such as mountain ranges and seas ensured that until the end of the Second World War this remained a point of some conjecture for Germans and non-Germans alike) and how its (potential) power could be restrained – issues that, until the total defeat of Nazi Germany, were never far from the forefront of European politics. Some analysts went so far as to say that there was – again largely until 1945 – a uniquely German political path (the so-called Sonderweg – see Box 1.1). The reasons for this are numerous, but in essence they revolve around the fact that Germans ‘failed’ to create a nation-state in the Middle Ages and, as a result, the cultural and political conflicts that took place around the time of the Reformation (1517) led Germany to institutionalise into a myriad of smaller units, all with predominantly German-speaking populations. A genuinely German state therefore took a long time to come into existence and, even then, the circumstances of its birth ensured that it adopted decidedly militaristic and expansionist poses (Fulbrook, 2002). Germany’s historical uniqueness subsequently came in its Kleinstaaterei (literally translated as ‘smallstatedness’). The British, French (and even, in many ways, the Americans), meanwhile, imposed – at a much earlier stage – statehood on their populations from the top down, and they now celebrate historic achievements, disastrous failures, lingering legacies and missed opportunities that their respective states have experienced over a number of centuries.

BOX 1.1 The German Sonderweg

The Sonderweg, or special path, is the subject of debate among historians about the development of Germany. The term was first used by German conservatives in the late nineteenth century, and over time it came to imply that Germany had taken a ‘special path’, from aristocratic rule through to democracy, that marked it out as different and, indeed, unique from other European states. This ‘specialness’ was often used to explain Germany’s behaviour in the international arena, and many of its advocates argue that it is a key explanatory variable in understanding the rise of Nazism. Critics of the Sonderweg thesis have argued that there is no ‘normal’ and ‘logical’ path that dictates political change, and that the experiences of France and the UK (as well as other states) were also quite distinct. Although the debate is one largely conducted by historians, it can still have an impact on the way in which many view current politics in Germany.

The absence of a German nation-state should not blind us to the fact that the collective beginnings of what could plausibly be understood as a German national identity can nonetheless be traced back a long way in history, perhaps even to the Germanic tribes’ famous defeat of the Romans in the Teutoburger Forest in AD 9. But agreeing on what constituted ‘Germanness’ was more tricky, and it was only towards the end of the eighteenth century that Germans began seriously to consider what this meant in practice. A further complication was that German nationality was, until very recently, understood as being granted on the basis of blood lineage (see Chapter 6). ‘Germans’ living many miles apart therefore felt some allegiance to one another through the prism of what came to be known as the Kulturnation (‘cultural nation’). Resolving to everyone’s satisfaction issues of where a German state, incorporating as many Germans as possible, should actually be therefore proved immensely difficult.

For hundreds of years, Germans lived, for the most part, in the Holy Roman Empire (AD 800–1815). However, defining and describing what that represented is also no easy task. At its simplest, it was a collection of territories united under an emperor who was elected by various Germanic states. It was not, though, a nation-state in the modern sense of the term and could never have become one, due to both its internal structures and the differing sets of interests that existed within it. A patchwork of small states, imperial cities, free cities, principalities, monarchies and duchies existed alongside each other. In more centralised countries, such as the UK and France, they would no doubt have long since disappeared. The problem was not resolved even when Otto von Bismarck created the first German nation-state in 1871, as many millions of Germans continued to live outside its borders.

From Holy Roman Empire to the Weimar Republic

This Holy Roman Empire therefore existed in spite of the fact that its people possessed little allegiance to it. It was characterised by both religious heterogeneity and strong territorial distinctiveness. It is not by chance that the names of some of contemporary Germany’s Länder (such as Saxony and Bavaria) reflect this historical territorial diversity, their names resonant of the long histories that they enjoy. The main (and, for many, only) common factor across the territory was the German language. Inhabitants of this diverse political landscape were also linked through various other phenomena that had their roots in this common tongue: German literature, German culture and a shared sense of a history of the German-speaking peoples all existed long before Germany existed as a political entity. Germany was a cultural nation, stressing linkages through shared customs, shared language and blood lineage. The ethos underpinning this understanding of ‘Germanness’ is something that remained (and in some ways remains) prominent in some aspects of contemporary politics, particularly when issues of immigration, nationality and citizenship are discussed (see Chapter 6).

This is not to say that there were no attempts to create a unified German state. There were, and they occurred periodically across the thirty-eight German territories that comprised the German Confederation (formed after the Congress of Vienna in 1815). The most famous of these movements came in 1848, when repeated calls were made for political freedoms, genuine democracy and national unity. Increases in nationalist rhetoric were noticeable as newspapers such as Deutsche Zeitung (‘German Paper’) increased in circulation, nationalist songs such as the Deutschlandlied (later to become Germany’s national anthem, see Box 1.2) by the poet August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben were written, and worries grew about possible advances by the French (on the Rhineland) and Danish (on Schleswig-Holstein in the north). Liberalism also gained political ground, and significant liberal pressures (such as calls for more individual rights and greater press freedoms) spread across the German-speaking lands. The increasing economic strength of Prussia led to the eventual creation of a customs union as more tangible feelings of economic interdependence spread across the German-speaking states. All of these factors nevertheless led each of the territories to experience what was to become an attempted revolution in slightly different ways. Some monarchs, fearing the fate of Louis-Philippe of France (who abdicated in 1848), accepted (albeit temporarily) some of the demands of the revolutionaries. Others defended their corner and rejected them out of hand. In the more southerly and westerly parts of Germany there were mass demonstrations as well as the creation of large popular assemblies.

BOX 1.2 The Deutschlandlied

The ‘Song of the Germans’, the country’s national anthem since 1922, was actually written by Joseph Haydn in 1797 to celebrate the birthday of Austrian Emperor Francis II. The lyrics for the Deutschlandlied were penned some forty-four years later by August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben. He began the first verse with the line ‘Deutschland, Deutschland über alles’ (‘Germany, Germany, above all’) as an attempt to prompt Germans to overcome the Kleinstaaterei of the era and to create a genuine German nation-state. Even before the Nazis deliberately appropriated this, it was controversial, and President Friedrich Ebert voiced his unhappiness as early as the 1920s. Both the first and second verses were later dropped, and on becoming the FRG’s anthem in 1952 the third verse – now beginning ‘Unity and justice and freedom’ – became the country’s official anthem.

No matter what form this dissent towards aristocratic rule took, the masses made similar claims: they wanted a free press, the freedom of assembly, and a parliament representing the German citizens instead of the federal council representing only the monarchs of the German states. That they ultimately failed in these aims can be attributed to a number of factors. First, the national parliament that was created in Frankfurt suffered from both weak leadership (mainly from Heinrich von Gagern, who was its most significant member) and the tendency to intellectualise and prevaricate. Second, the revolution enjoyed no military support. Third, there was a major divide between those who favoured a Großdeutschland (Greater Germany, which would have included Austria) and those who were happy for Austria to remain outside the state’s borders, while there were also regular disagreements over a range of matters between Prussia and some of the southern German states. Finally, the fact that there were no political parties involved did not help in facilitating agreement and channelling interests into compromise solutions. By late 1848, plans to institutionalise German unity were starting to crumble as the military and the aristocracy began to regain their composure and subsequently the political upper hand. By 1851, almost all of the achievements of the revolutionaries across Germany had been revoked, the national assembly had disintegrated and the old order had been restored.

Germany had to wait another twenty years before Otto von Bismarck, a long-time schemer involved in the failure of the 1848 revolution, changed all this to create a fully fledged nation-state. Bismarck was a conservative politician from Prussia, the strongest of all the German territories. He was determined to unite the German states into a single empire (with the exception of Austria) with Prussia at its core. Beginning in 1884, Germany also began to ape Europe’s traditional Great Powers by acquiring several colonies in Africa, including German East Africa and the territories that are now Namibia, Togo and Cameroon.

As Bismarck was initially unable to persuade all of the German states to join him in forging this new and more powerful empire under Prussian leadership, he provoked war with both Austria and later France as a way of uniting the German-speaking states behind him. His plan worked, and following Prussia’s crushing victory in the ensuing conflict, the Deutsches Kaiserreich (German Empire) was declared in Versailles in 1871, with Wilhelm I of Prussia as Kaiser (Emperor) and Berlin as the new capital. As ‘Chancellor’ of the new Germany, Bismarck concentrated on building a powerful state with a unified national identity (see Pulzer, 1997). To this end, and given Prussia’s Protestant religious profile, he targeted the Catholic Church (in what was termed the Kulturkampf), which he believed had too much influence (particularly in southern Germany); indeed, the sectarian divisions between Catholics and Protestants still retain occasional relevance in German politics today. He also aimed to prevent the spread of socialism, partly by introducing national health insurance and pensions, thereby laying the foundations of the modern welfare state, not only in Germany but throughout Europe (see Chapter 8).

In the early period following the first unification of Germany, Emperor Wilhelm I’s foreign policy secured Germany’s position at the forefront of international affairs by forging (sometimes uneasy) alliances with neighbours and purposefully using diplomatic means to isolate France. Under his grandson Wilhelm II, however, Germany, like a number of other European powers, became more overtly imperialist, and this contributed to Europe slipping towards war. Many of the alliances that German leaders crafted were not renewed over time. New alliances between other states also slowly began to exclude Germany. France, Germany’s traditional foe in Central/Western Europe, even established new relationships with its traditional enemies, such as the United Kingdom (most notably in the ‘Entente Cordiale’ of 1904) and Russia. As war became ever more likely, Germany found itself on the same side as Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire in an alliance that came to be known as the Central Powers (on the basis that they were all located between the Russian Empire in the East and France and the UK in the West).

The assassination of Austria’s crown prince, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, on 28 June 1914 ultimately triggered the opening of hostilities in what became the First World War. The unsuccessful Central Powers, headed by Germany, suffered defeat against the Allied Powers in what was up to then the bloodiest conflict of all time. Eventually, a revolution broke out in November 1918 in Germany, and Wilhelm II and all the German ruling princes abdicated their thrones. An armistice putting an end to hostilities was signed on 11 November 1918 and Germany was compelled – in June 1919 – to sign the Treaty of Versailles in the very building where Bismarck had called the German Empire into existence forty-eight years previously. The treaty was perceived by many in Germany as a humiliating continuation of the war by other means and its harshness is often cited as having facilitated the later rise of Nazism.

The Weimar Republic and the Rise of Nazism

The proclamation of a republic in the immediate aftermath of the First World War led to the meeting of a constitutional convention in the sleepy town of Weimar in what is now the eastern German state of Thuringia. The constitution of the ‘Weimar Republic’ was in many ways an exemplary document, offering Germany the opportunity to distance itself from its militaristic and imperial past and recast itself as a liberal, democratic state in the tradition of older democracies such as France, the UK and the USA. However, as is well known, what looked good in theory proved much less impressive in practice, and the new political system’s democratic credentials failed to stand the test of time.

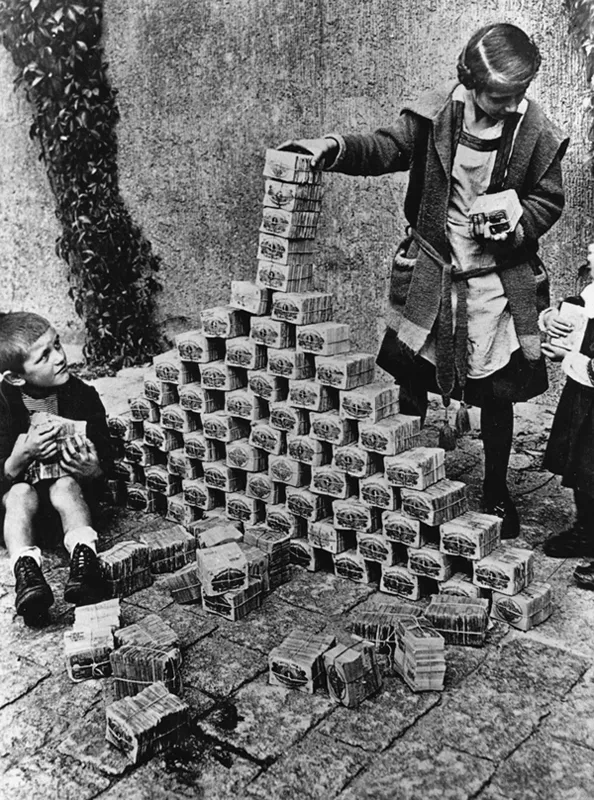

One of the reasons why the Weimar Republic failed was the desolate economic situation from which Germany never really recovered after 1918. Like other countries, the First World War almost bankrupted Germany, and this, when combined with the high levels of reparations imposed in the Treaty of Versailles, left the republic very vulnerable economically. But worse was to come. In the early 1920s, and partly as a result of the war, Germany was struck by gradually worsening hyper-inflation. This culminated in late 1923, by which time the value of its currency was depreciating on an almost daily basis to the extent that whole wads of money had greater value as building blocks for children to play with than as a medium of exchange. The effects of hyperinflation were devastating, and it destroyed any remaining wealth not already lost in the ravages of the First World War, leaving millions in poverty (Feldman, 1997). This left a deep and unmistakable imprint on German society, which was later also responsible for the strong role of the Bundesbank in (West) Germany’s monetary policy (see Chapter 7).

During the mid-1920s, the German economy recovered somewhat, and many parts of the country enjoyed both economic and cultural revivals. Berlin, in particular, experienced what came to be known as the ‘Golden Twenties’, in which – for a short period – the better-off residents appeared to be enjoying an exciting, extremely vibrant and positively hedonistic lifestyle. Although this period lasted little more than a decade, sophisticated and innovative approaches to architecture and design (notably the Bauhaus school) prospered across Germany, and literary figures (such as the poet Bertolt Brecht), film-makers (such as the Austrian Fritz Lang, director of Metropolis), artists, fashion designers and musicians all excelled. Although Berlin was the centre of this movement, once the hyperinflation catastrophe had been overcome, the diffuse and diverse forces involved spread throughout the country. But the movement did not last long. Those on the right of the political spectrum were highly suspicious of what they perceived as a socially disruptive and dangerous development, and with the increasing influence of right-wing parties through the late 1920s and early 1930s came increasing intolerance towards such alleged decadence. When the economy was once again hit hard by the Great Depression of the early 1930s (which spread following the 1929 Wall Street Crash), the Golden Twenties came to an abrupt end.

Figure 1.1 The ravages of hyperinflation: German children use banknotes as building blocks, 1923

The erratic nature of the economy allowed anti-system parties of both the left and right to dominate political discourse and, before long, Germany found itself once again slipping towards authoritarianism (Evans, 2004). By 1932, the combined shackles of the Great Depres...