eBook - ePub

The Handbook of Maritime Economics and Business

- 1,096 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Handbook of Maritime Economics and Business

About this book

This book is the founding title in the Grammenos Library. The diversity of the subjects covered is unique and the results of research developed over many years are not only comprehensive, but also have important implications on real life issues in maritime business. The new edition covers a vast number of topics, including: • Shipping Economics and Maritime Nexus • International Seaborne Trade • Economics of Shipping Market and Shipping Cycles • Economics of Shipping Sectors • Issues in Liner Shipping • Economics of Maritime Safety and Seafaring Labour Market • National and International Shipping Policies • Aspects of Shipping Management and Operations• Shipping Investment and Finance • Port Economics and Management • Aspects of International Logistics

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Handbook of Maritime Economics and Business by Costas Grammenos, Costas Grammenos,Costas Th. Grammenos in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Law Theory & Practice. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Shipping Economics and Maritime Nexus

Chapter 1

Maritime Business During the Twentieth Century: Continuity and Change

Gelina Harlaftis* and Ioannis Theotokas†

1. Introduction

The historical process is dynamic, and the changes that occurred during the course of world shipping in the past century, embedded some of the structures of the nineteenth century. The methodological tools of a historian and an economist will be used in this chapter, tracing continuity and change in the twentieth century shipping by examining maritime business at a macro-and micro level. At the core of the analysis lies the shipping firm, the micro-level, which helps us understand the changes in world shipping, the macro-level.

The shipping firm functions in a specific market, and the shipping market can only be understood as an international market, in a multiethnic environment. The first part of this chapter follows the developments in world shipping, analysing briefly the main fleets, the routes and cargoes carried, the ships and the main technological innovations. The second part provides an insight on the main structural changes in the shipping markets by focusing on the division of liner and tramp shipping. The third part reveals from inside the shipowning structure and its changes in time in the main twentieth century fleets: the British, the Norwegians, the Greeks and the Japanese; it is remarkable how similar their organisation and structure proves to be.1 Maritime business has always been an internationalised business. In the last five centuries of capitalist development, European colonial expansion was only made possible with the sea and ships; the sea being but a route of communication and strength rather than of isolation and weakness. Wasn’t it Sir Walter Raleigh in the late sixteenth century, one of Elizabeth’s main consultants who had set some of the first rules for the British expansion? “He who commands the sea commands the trade routes of the world. He who commands the trade routes, commands the trade. He who commands the trade, commands the riches of the world, and hence the world itself.” The real truths are tested in history and time.

2. Developments in World Shipping

There were two main developments in the nineteenth century that pre-determined the path of the world economies: an incredible industrialisation of the West and its dominance in the rest of the world. During that period the world witnessed an unprecedented boom in world exchange of goods and services, an unprecedented boom of international sea-trade. The basis of the world trade system of the twentieth century was consolidated in the nineteenth century: it was the flow of industrial goods from Europe to the rest of the world and the flow of raw materials to Europe from the rest of the world. In this way, deep-sea going trade became increasingly dominated by a small number of bulk commodities in all the world’s oceans and seas; in the last third of the nineteenth century, grain, cotton and coal were the main bulk cargoes that filled the holds of the world fleet. At the same time, the transition from sail to steam, apart from increasing the availability of cargo space at sea, caused a revolutionary decline in freight rates, contributing further to the increase of international sea-borne trade. Europe, however, remained at the core of the world sea-trade system: until the eve of the World War I, three quarters of world exports in value and almost two thirds of world imports concerned the old continent.2

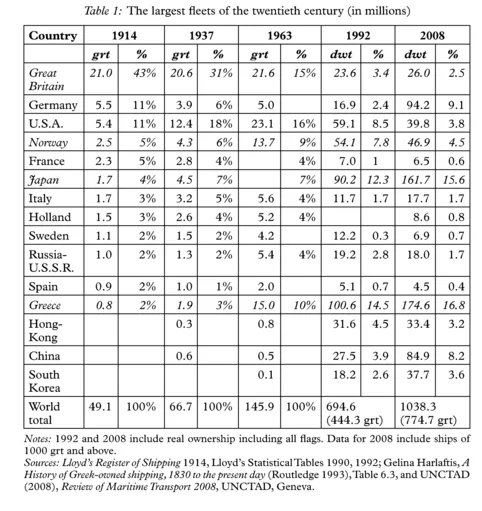

It does not come as a surprise then, that European countries owned the largest part of the ocean-going world fleet during this period. Due to technological innovations, the international merchant fleet was able to carry an increasing volume of cargoes between continents with greater speed and lower cost. By the turn of the twentieth century Great Britain was still the undisputable world maritime power owning 45% of the world fleet, followed by the United States, Germany, Norway, France and Japan, (see Table 1). Over 95% of the world fleet belonged to 15 countries that formed the so-called “Atlantic economy”; what is today called the “developed” nations of the OECD countries. Meanwhile, at the rival Pacific Ocean, Japan was preparing to be the rising star of world shipping in the twentieth century.

Pax Brittanica and the incredible increase of world economic prosperity of more than one hundred years closed abruptly with the beginning of World War I. The main cause was the conflict of the big industrial European nations for the expansion of their economic and political influence in the non-European world. It was the result of the competition of western European nations for new markets and raw materials that determined the nineteenth century and peaked in the beginning of the twentieth century as the influence of the industrialisation of western European nations became more distinct. At the beginning of the twentieth century almost all of Asia and Africa were in one way or another under European colonial control.

The factors that created the international economy of the nineteenth century proved detrimental during the two destructive world wars of the twentieth century by multiplying their effects. Firstly, the formation of gigantic national enterprises in Europe and the United States and their concentration in vast industrial complexes with continuous amalgamations of small and medium companies resulted in an exponential increase of world production. Second, the search for markets beyond Europe that would absorb the excessive industrial production, resulted in the fierce competition of British, German, French and American capital in international capital investments worldwide. The result was the creation of multinational companies and banks that led to the development of monopolies on a national and international level. Within this framework, the great expansion of the United States and German fleets took place, along with the multiple

mergers and acquisitions in the northern European liner shipping business and the gradual destruction of small tramp shipping companies, particularly in Great Britain.

The interwar economy never recovered from the shock of World War I that influenced the whole structure of the international economy resulting in the worst economic crisis that the industrial world had seen in 1929. During the interwar period world shipping faced severe problems stemming from a contracting world sea-trade, decreasing world immigration and increasing protectionism. The economic crisis did not affect the main national fleets in the same way. The impact was particularly felt in Britain. This is the period of the economic downhill of mighty old Albion. It was World War I that weakened Britain and allowed competitors to challenge its maritime hegemony. The withdrawal of British ships from trades not directly related to the Allied Cause opened the Pacific trades to the Japanese. Moreover, both Norway and Greece were neutrals, which meant that their fleets were able to profit from high wartime freight rates (Greece entered the war in 1917). Norwegian and Greek ships were able to trade at market rates for three years while most of the British fleet was requisitioned and forced to work for low, fixed remunerations. Freight rates in the free market remained high until 1920, after which they plummeted; while there was a brief recovery in the mid-1920s, the nadir was reached in the early 1930s.

Table 1 records the development of the world fleets of the main maritime nations from 1914 to 1937. During this period the world fleet increased at one third of its prewar size. The British fleet remained at the same level with a slight decrease of its registered tonnage, but its percentage of the ownership of the world fleet decreased from 43% to 31% due to the increase of the fleets of other nations. The interwar period was characterised by the unsuccessful attempt of the United States to keep a large national fleet with large and costly subsidies to shipping entrepreneurs. Most of the increase of the world fleet in the interwar period apart from the US was due to the Japanese, the Norwegians and the Greeks, who proved to be the owners of the most dynamic fleets of the century. Their growth was interconnected with the carriage of energy sources. The most important change in the world trade of the interwar period was the gradual decrease of the coal trade and the growing importance of oil.

The main coal producer (and exporter) in 1900 was the UK, with 225 million metric tons or 51% of Europe’s production. By 1937 Britain was still Europe’s main producing country with 42% of European output. In 1870 the production of oil was less than 1 million tons and in 1900 oil was still an insignificant source of energy; world production of 20 million tons met only 2.5% of world energy consumption. Because production was so limited there was little need for specialised vessels; tankers, mostly owned by Europeans, accounted for a tiny 1.5% of world merchant tonnage. But all this changed in the interwar period: by 1938 oil production had increased more than 15 times; it was 273 million tons and accounted for 26% of world energy consumption.3 The tanker fleet, had grown to 16% of world tonnage, and although it was mostly state-owned, independent tanker owners started to appear in the 1920s. The largest independent owners of the interwar period were the Norwegians.4

Technological innovations continued in the twentieth century; the choices and exploitation of technological advances by shipping entrepreneurs determined the path of world shipping. The first half of the twentieth century was characterised on the one hand by the use of diesel engines and the replacement of steam engines and on the other, by the massive standard shipbuilding projects during the two world wars. Diesel engines that appeared in 1890 were only used in a more massive scale on motor ships during the interwar period particularly in Germany and the Scandinavian countries; the cost of fuel being 30% to 50% lower than that of the steam engines. Standardisation of ship types and shipbuilding programmes were introduced in World War I when Germans sunk the allied fleets in an unprecedented submarine war. The world had not yet realised what industrialisation and massive production of weapons for destruction could do. The convoy system had been abandoned and naval battleships with their complex weapons were ready to confront the enemy. But it was the allied merchant steamships that were the artery of the war, transporting war supplies. And this armless merchant fleet became an easy target to the new menace of the seas: the German submarines. From 1914 to 1918, 5,861 ships or 50% of the allied fleet was sunk.

Replacement of the sunken fleet took place between 1918 to 1921 in US and British shipyards. It was the first time that standard types of cargo ships, the “standards” as they came to be called, were built on a large scale. The “standard” ships became the main type of cargo ship during the interwar period; they were steamships of 5,500 grt. It was these “standard” ships that Greeks, Japanese and Norwegian tramp operators purchased en masse from the British second hand market and expanded their fleets amongst the world economic crises. For similar reasons during World War II the United States and Canada launched the most massive shipbuilding programmes the world had known, using new and far quicker methods of building ships: welding. During four years they managed to build 3,000 ships, the well-known Liberty ships, that formed the standard dry-bulk cargo vessel for the next 25 years.5 Greek, Norwegian, British and Japanese tramp operators all came to own Liberty ships, in one way or another up to the late 1960s.

The second half of the twentieth century was characterised by an incredible increase of world trade that towards the end of the century was described as the globalisation of the world economy. The period of acceleration was up to 1970s; world trade from about 500 million metric tons in the 1940s climbed up to more than three billion metric tons in the mid-1970s. If the history of world maritime transport in the first half of the twentieth century was written by coal and tramp ships, in the second half the main players were oil and tankers. During this period, sea-trade was divided into two categories: liquid and dry cargo. Almost 60% of the exponential growth of world sea trade was due to the incredible growth of the carriage of liquid cargo at sea, oil and oil products. There was also impressive growth in the five main bulk cargoes: ore, bauxite, coal, phosphates and grain. To carry the enormous volumes required to feed the industries of the West and East Asia, the size of ships carrying liquid and dry cargoes had to be increased. The second half of the twentieth century was characterised by the gigantic sizes of ships and their specialisation according to the type of cargoes. The last third of the century was marked by the introduction of container ships. The new “ugly” ships revolutionised the transport system for industrial goods.

Up to the 1960s the main carriers of the world fleet remained the same with the US and Britain continuing to hold their decreasing shares in world shipping, followed by the continually rising Greece, Japan and Norway (Table 1). Flags of convenience were used informally by all maritime nations but in the immediate...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Preface to the First Edition

- Contents

- List of Contributors

- Part One: Shipping Economics and Maritime Nexus

- Part Two: International Seaborne Trade

- Part Three: Economics of Shipping Markets and Shipping Cycles

- Part Four: Economics of Shipping Sectors

- Part Five: Issues in Liner Shipping

- Part Six: Pollution and Vessel Safety

- Part Seven: National and International Shipping Policies

- Part Eight: Aspects of Shipping Management and Operations

- Part Nine: Shipping Investment, Finance and Strategy

- Part Ten: Port Economics and Management

- Part Eleven: Aspects of International Logistics

- Index