![]()

THE SEARCH WIDENS: EXPLORING ITALY

![]()

Strolling Through Time

When Rome falls—the World

Lord Byron, Childe Harold

In 146 BC the Greeks were conquered by a new aggressive people—to the Greeks they were barbarians—known as Romans.

Though they developed and kept their own language, Latin, they absorbed much from the artistic and intellectual culture of the Greeks. In the next three centuries they assembled an empire stretching over the then known world west of Persia, including Egypt, Greece, Asia Minor, Syria, and much of what we now call Western Europe. The nerve center for this vast empire was the Roman Forum—perhaps the most historic and valuable small piece of real estate in the world. Just as the caves epitomized prehistoric man, the pyramids the Egyptians, and the temple the Greeks, so did the Forum epitomize the Romans.

The world forum, akin to Latin foris (outside) and fores (door), came to mean a marketplace or public place to conduct judicial and public business. Forums, or open gathering places, were located in most Roman cities. In legal terms the word is equivalent to “court” or “jurisdiction.” Basilicas, law courts, temples, and other public buildings clustered there. In short, the forum was the heart of the city.

The Roman forum lay between the Palatine and Capitoline Hills. Here vestal virgins tended temples, the Senate met, policy was enacted, officers were elected, Caesar was assassinated, and triumphal processions were held on great occasions. It was and is a focal point of history.

Like thousands over the centuries, I have gone to Rome's Forum and felt the power of the past speak through the majestic ruins. It is steeped in memory, glory, and blood. If popular culture has a leading shrine in the ancient world, this is it.

The process of Romanization carried with it much of the popular culture of the vast empire and made Latin the universal language of the Empire. The Forum was the center around which the known world, the orbis terrarium, turned.

The Romans kept centuries of peace, the famous Pax Romana. Their Empire finally crumbled, but the city itself still flourishes, having transferred authority from emperors to popes.

The Tiber River winds its way through Rome, as it has done for thousands of years. If it could talk, what tales it would tell! This is the home of many of the ideas and achievements that sustain Western civilization, and make America proud to think of itself as the New World Rome.

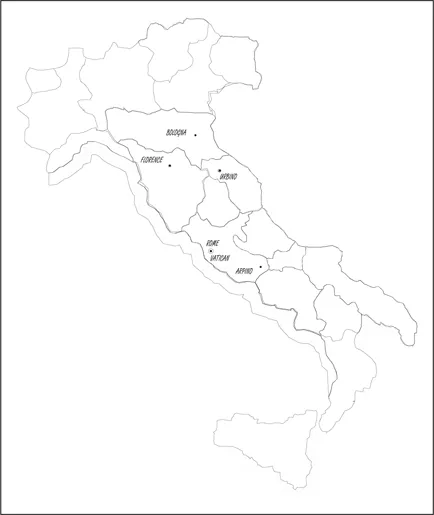

We shall not attempt to retell the oft-told tale of that forum and city but will focus on a pivotal person in our story—Marcus Tullius Cicero, born on January 3, 106 BC, in the family homestead outside Arpinum sixty miles southeast of Rome. Arpinum still boasts a fine statue of Cicero in the town square. I like to walk through the Porta deH'Arco, a gate of the old wall.

The local town school is named after Cicero, and from the town one can look out at the fertile, sun-drenched rural Italy that he loved. Who there could have guessed, then or now, that he would play a pivotal role in history, becoming the godfather of our popular culture? That his words would outlast the mighty Roman Empire? If we listen carefully, we may realize that the past is prologue, and that nothing is new under the sun.

I never tire of strolling through Rome. Neither did Cicero. It is one of the great cultural centers of the world, whose history begins in the mist of the Neolithic and Bronze ages. Tribes gathered and prospered here when history was still blind. Later the Etruscans developed and dominated the city by the sixth century BC.

Ideally located on the Tiber River, surrounded by undulating plains, Rome became the city of Seven Hills (Aventine, Caelian, Capitoline, Esquiline, Palatine, Quirinal, and Viminal). The gods favored this place. By 500 BC state temples were erected to Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva. Ever since then, Rome has played a major role in Western history, becoming the spiritual capital of the Roman Catholic Church, and political capital of Italy.

Folklore and mythology combined to declare that the struggling settlement on the Tiber was saved by two gallant warriors, Romulus and Remus, who were kept alive by a wolf. The name Rome was taken from Romulus. For many years a caged wolf was displayed to honor the original wolf. At some point Rome, the city-state, decided to expand and incorporate other settlements. Tough and aggressive, the Romans succeeded.

First they dominated other places in Italy. When they were strong enough, they built a fleet and entered the Mediterranean world. Having gained a foothold in the Maghrad, the African province later known as Tunisia, they confronted the powerful city of Carthage.

Twice defeated by Rome, Carthage was razed to the ground in the second century BC. Rome was empire-bound, and ended up with the largest the Western world had seen. By mid first century BC the empire stretched from Britannia in the north, Lusitania (later Portugal) in the west, Egypt in the south, to Antioch and Sinope in the east.

With such a history comes a style. St. Ambrose (AD ca. 339/340–397) made a famous pronouncement about it: Si fueris Romae, Romano vivito more (If you are in Rome, live in the Roman style). Cicero did, and transmitted that style into the world's imagination. That is why I stroll time and again through Rome. Come take a stroll with me.

Rome, the Eternal City, is our starting point for an overview of the classical world. The home of many ideas and achievements that make America think of itself as the New World Rome. The home of Cicero, the godfather of Western popular culture, and its patron saint.

When you're tired of Rome, You're tired of living. It teems with life, drama, fun. So many Romes: Rome of the Emperors, and Republic, the Caesars, and Popes. Roma, non basta una vita (One lifetime isn't enough to see Rome).

In our new century and millennium some think we have conquered both space and time. We can fly to the moon, send tourists into outer space, and discover new galaxies billions of miles away. There is no day or night on e-mail and the Internet. They work 24/7 and some of us seem to be reaching all work-no rest in our daily lives. One reason we like Italy is because people there still have time to rest, relax, and celebrate. Old customs and holidays are still observed; old ghosts still haunt the land. I am here to confront the ghost of Cicero. Does it still come to the Roman Forum after all these years? How does one search for him today? How can we open the doors of time?

I continue my Cicero search in a cold Roman rain, which dampens bodies and spirits. When it rains in Paris, they say it dampens poets' souls. When it rains in Rome, everything leaks.

Roofs leak. Buses leak. Awnings leak: to pass under one over a sidewalk café is like getting a cold morning shower. Humanity rebels. Waiters make threatening gestures at the heavens, but the old gods are not impressed. If Bacchus and Venus came back in their flimsy spring garb, they might well catch pneumonia.

Because Italy is by common consent bella, people refuse to act or dress as if the weather can be brutto (bad) or piovoso (rainy)—which it is, for weeks at a time. Italians wear the same open shoes and light clothes that are elegant when dry, unbearable when wet. Few have boots, fewer still overshoes. Not only psychology but economics comes into play. Clothes and boots are very expensive. Given the choice, many favor food, cars, or la dolce vita. After all, who can picture the good life in overshoes?

Behind all this is the idea of èssen di moda, to be in fashion; to hold up to the world la bella figura, the good appearance, the stylish look. What Italians do everything to achieve, the rain washes away. Little streaks of mascara appear on shop girls' painted faces; elaborate ringlets are transformed into masses of dripping hair; shoes squish as water escapes between socks and soles. The world is undone. La bella figura needs sunshine, chiaroscuro, mirror images, light, bare flesh, laughter.

Who wants to tour in a driving rain? Down the streets an imposing soggy structure houses the state library. This might be a good time to begin reading. I enter to find a sign on the desk: “Closed temporarily because of rain.” I smile. This must be a joke: but no. Staff members have abandoned books for buckets, to be maneuvered so as to catch the maximum drips.

I walk over to a desk of the director, for he alone has no bucket. Like a general, he directs his bucketeers. I ask the obvious question.

“Why don't you have the roof fixed?”

“The job was approved a year ago,” he replied, taking off his hornrimmed glasses and wiping away the moisture. “No one has shown up to do it yet.”

“Don't you complain?”

“Continuously. Perhaps that's why no one ever comes. The Minister of Public Works says not to worry. It never rains much after May. Then I say ‘Why don't you explain that to the books?’ He hangs up.”

I like the look in his eyes, and his smile. A librarian in charge of water buckets—not an enviable position.

“Maybe we can't fix the roof, but we fix good coffee. Would you like a cup?” We walk to a side room, and wait for the coffee to perk.

“You are an American?”

“Yes.”

“Americans come to Italy with a heavy load—not just clothes and cameras, but preconceptions. The whole travel experience—the plastic tourist world—is encrusted with clichés. Rome has the largest cliché bank in the world. I think that we should issue cliché credit cards along with copies of Mark Twain's The Innocents Abroad, amusing and instructive.”

Was he warning me not to be another innocent? Have I already absorbed too many clichés about Cicero, dead for centuries? Do I have to prove anything? Can't I just search for Cicero because I want to?

I finish my coffee, wish my friendly librarian well, and go back out on the street. Rain or shine, Rome has so much to see. A patched petticoat, put out to dry on an overhead balcony, doesn't dry but wets. Raindrops fall on heads. Romans describe their situations with words found in no dictionary. Then each walks off to his own destiny amid the gray decay.

Despite the overcast sky, enough light is present to see what a tired old lady Rome really is. A thousand cracks and sags appear that never show in sunshine. Bricks, having soaked up water like sponges, conceal their edges and shapes. Pigments fade. Quaint old stone pavements cradle muddy puddles, which guarantee wet feet. Potholes fill with water, ruining shoes or tires. Rust shows on metal signs and shields that would seem bright and fresh in sunshine.

Did John Keats ever walk down this street in the rain? Did the muddy puddles affect him as they do me? Was the rain splashing off the Spanish Steps that last time he looked out of his window, just before he died? Did he still believe that beauty was truth, and truth beauty?

Here and there umbrellas pop out; far too many for the narrow sidewalks and walkways between illegally parked cars. The gladiators have gone: now the umbrella holders fight for priority and position. Often the walker, who happens to be where an umbrella wants to be, bears the blow. When it rains in Rome, it's a pain in the neck.

Nostalgia sets in. A music shop plays a record of an Italian love song. One remembers days when the streets of Rome were full of people playing at being nymphs or saucy satyrs—swaying in the sunshine, eyeing American girls, admiring la bella figura. These very shops, dark and deserted now, were packed with affluent visitors who confused one and ten thousand lire notes, cheerfully paid overcharges, and surrendered traveler's checks as if they were giveaway coupons. Eyes met and flesh touched flesh; talking of meeting in the cappuccino bars, or hotels.

“Europe,” Gogol wrote, “compared to Italy is like a gloomy day compared to a day of sunshine.” He must not have been in Rome during a soaking April rain.

Even the dogs are wet and sad. Rome abounds with guard dogs, Dobermans, German shepherds, Great Danes. With terrorism unchecked, and the police ineffective, what else can one do? In the 1960s the ultimate status symbols were large cars and small dogs. Now the formula is reversed: the smaller the car and the larger the dog, the better.

Dogs must be walked. They don't like the Roman rain any more than their masters. They too must brave potholes, vie for space, suffer the outrages of splashes from speeding cars. Many are muzzled, a further indignity for beasts of considerable character and value. Two muzzled German shepherds approach, growl, and try to show their teeth. The tight muzzles hurt, so do the leashes, pulled choke tight to avoid an encounter. To av...