- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Internet

About this book

From music to gaming, information gathering to eLearning; eCommerce to eGovernment, Lorenzo Cantoni and Stefano Tardini's absorbing introduction considers the internet as a communication technology; the opportunities it affords us, the limitations it imposes and the functions it allows.

Internet explores:

- the political economy of the internet

- hypertext

- computer mediated communication

- websites as communication

- conceptualizing users of the internet

- internet communities and practices.

Perfect for students studying this modern phenomenon, and a veritable e-feast for all cyber junkies.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF THE INTERNET

The internet is no doubt one of the newest and most powerful instances of information and communication technology (ICT). Yet, what does it mean to call the internet an instance of 'communication technology'?

Communication can be defined as an exchange of signs that produces a sense, i.e. an exchange of messages. The basic nature of the messages/ signs that are exchanged in a face-to-face (FTF) communication event tends to be oral/acoustic: basically, communication relies on the consequence that a physical fact (mainly, a piece of sound) refers to a non-physical fact, i.e. a piece of meaning, a linguistic value (Rigotti and Cigada 2004: 23–31; see also Bühler 1982; Clark 1996; Jakobson 1960; de Saussure 1983). We can conceive of an FTF conversation as the most basic form of human communication; in a communicative event such as a conversation between two friends speaking and facing each other, no recognizable technology is involved, although language is itself a medium: communication just occurs by means of spoken language (and – of course – by means of the speakers' phonatory and auditory systems, i.e. mouth, tongue, vocal chords, ears, and so on; and by means of the air as well, where sound-waves spread through). But as soon as we move away from an FTF conversation, human communication takes place under the mediation of some kind of technology: it can be mediated through writing – the basic form of communication technology – or through different media, such as radio, telephone, a video-conference system, chat, television, and so on.

In a broader sense, a technology is everything purposely created by humans for a well-defined goal (ad artem). A technology of communication is a technology created in order to support, to facilitate, to foster and to enhance communications. In this sense, the sense of human communications, whatever is invented, created or used in order to support communication is a communication technology, or, after Ong, 'technologies of the word' (Ong 2002).

At the risk of sounding clichéd, the internet was not invented by anybody who woke up one morning and said: 'Let's have an internet!' It did not arise from a 'zero context'. So, with this in mind, and to avoid the common mistake of thinking that for the first time in the history of the world a new communication technology has brought along important social changes, it is crucial to understand the context in which the internet has spread and the historical stages that led to its invention. The internet, in fact, emerged in a context where other communication technologies pre-existed, which have their own role and their own history, which in their turn have taken the place of other technologies, and so on.

This opening chapter therefore presents the context in which the internet has emerged and is spreading from both a sociological and historical perspective. Presenting the details of this context is crucial if we are to avoid the pitfalls of imagining that the internet's development is unique in the history of communications and believing that the internet developed as a technology divorced from other social factors. Furthermore, any serious study of the internet needs to proceed from an acknowledgement that the internet carries with it the heritage of a number of forms of communication that preceded and coexist with it. The first section (1.1), then, deals with the relationship between technologies and society in order to reveal the mutual influences between them; the second section (1.2) provides a historical overview of the development of the technologies of the word; then a taxonomy for the analysis of the technologies of the word is presented, which proves to be very useful with regard to the internet as well (1.3); in the fourth section (1.4), the history of the development of the internet is briefly sketched to show where the present interests, patterns of ownership and struggle for control of the internet have come from; finally, the present context from where the internet is spreading is described, along with an introduction to the main political, economic, legal and ethical issues it throws up (1.5).

1.1 COMMUNICATION AND TECHNOLOGIES: A SOCIOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE

As we have indicated, the internet is not the first communication technology to have appeared, nor has it developed in a socio-political vacuum. In this section we are going to focus on the close relationship between communication and technology from a sociological perspective. In particular, we will introduce the most relevant ideas from diffusion theories, i.e. those theories that explain how technological innovations enter a community of people (1.1.1), what are the possible attitudes of people towards new technologies (1.1.2), and what is the process that leads a technology to be (or not to be) adopted and to spread within a community (1.1.3). Then we will focus on the appearance and diffusion of new communication technologies in particular, analysing their relationship to other pre-existing communication technologies, the phenomenon of so-called 'mediamorphosis' (1.1.4).

1.1.1 The diffusion of technological innovations

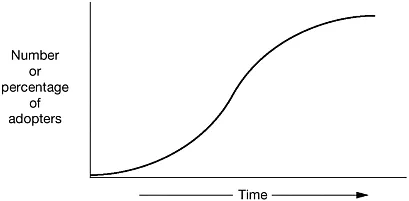

When a new technology becomes available on the market, the way by which it comes to be adopted within a social community usually does not follow a linear and continuous path (see Figure 1.1). The study of the impact of new technologies on social groups shows that the process of adoption (or refutation) of technologies can be very complex and manifold.

Two models can help us in explaining the diffusion of innovations: the model of linguistic change and that of ecological systems:

1 The model of linguistic change explains the phenomenon of innovations in human languages: that is, how a new element (a new word, a new syntactical construction, and so on) enters the language system and gets to be used by a given community. The introduction of a new element into the language follows three steps: the new element is created/ invented by someone who first coins it and uses it or a new sense is given to an existing element (innovation): 'everything in which the speech goes far from the existing models of the language in which the speech is established is an innovation' (Coseriu 1981: 55). The new element is then adopted and used by the hearer (adoption): 'the acceptance of an innovation by the hearer as a model for further expressions is adoption' (Coseriu 1981: 55). Finally, the new element spreads in the system; for instance, a word becomes part of the lexicon of a language, is inserted in the language dictionaries, and so on (change): 'linguistic change is the

Figure 1.1 An S-curve represents the rate of adoption of an innovation over time

Source: Fidler 1997. With permission.

diffusion or the generalization of an innovation, that is, necessarily, a series of subsequent adoptions' (Coseriu 1981: 56; see also Cantoni and Di Blas 2002: 30).

Technological innovations follow similar steps in their diffusion: a new technology is first invented; it is then adopted by a small community; it finally spreads in a society, partly overlapping with other existing technologies, partly overcoming old ones.

2 The impact of a technological innovation on the context in which it is inserted (a society, a community, an organization) can be well explained through the comparison with an ecological system. Ecological systems have two basic features:

a) They are high-interdependence systems, i.e. all the elements of the system are highly interdependent with one another. This means that a little change made in a part of a system, such as, for instance, the arrival of a new animal species in a part of the system – let us say a lake – has consequences on the whole system: all the other elements will be somehow affected by the change, some more directly, some less so. For instance, all the animal species that were already present in the system will have their space reduced, the food chain of the system will necessarily be modified, and so on.

b) Ecological systems are also characterized by the non-reversibility of their processes: once a process takes place, it is impossible to return to the status of the system before the process. If, for instance, a pollutant is spilled into the lake, it will have such an impact on the lake's flora and fauna that it will be impossible to completely eliminate the pollutant and, as if nothing had happened, let the lake return to the way it was before.

High interdependence and non-reversibility are important features of communication systems as well. When a new communication technology is adopted, for example, by an organization, the adoption will affect the whole organization, since the new element necessarily gives rise to a reorganization of the whole system. If one introduces e-mail in an organization, the new element will necessarily be used for some tasks that were before carried out by means of fax, phone, mail or express carrier; each one of the 'old' technologies will thus have to re-negotiate its field of action (its territory) with e-mail; and if one then decides, for unpredictable reasons, to eliminate e-mail from the organization, one will never be able to restore the situation as it exactly was before the adoption of e-mail.

Since the second half of the last century, diffusion theories have analysed the diffusion of innovations in given social contexts. Everett M. Rogers defines an innovation as 'an idea, practice or object that is perceived as new by an individual or other unit of adoption' (Rogers 1995: 11), and diffusion as 'the process by which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among the members of a social system. It is a special type of communication, in that the messages are concerned with new ideas' (Rogers 1995: 5). We notice here that the novelty of an innovation is defined on the basis of the perception that a unit of adoption has of it, and not of its intrinsic qualities, i.e. of its 'real' novelty. Let's introduce the subject through two well-known examples, taken from Rogers' book Diffusion of Innovations:

1 The first example has nothing to do with communication technologies, actually it refers to something that can be considered a technology in a very broad sense: water boiling.

After the Second War World, the Peruvian public health service tried to introduce boiling of drinking water in a little Peruvian village, Los Molinas. During the two-year campaign, the service sent a health worker, Nelida, to the village whose task was to persuade the housewives of the village to add water boiling to their pattern of daily behaviour. In two years, Nelida was able to persuade only 5 per cent – 11 families! – of Los Molinas population to adopt the innovation.

Why did the adoption of this important and healthy innovation fail? First of all, because of the cultural beliefs of the villagers: in her campaign Nelida did not take into account the hot–cold belief system (see Helman 2001), which is very common in most nations of Latin America, Asia and Africa. According to these beliefs, water is a 'cold' element, and boiling it would have made it 'hot', i.e. appropriate only for sick persons. Second, social reasons prevented the innovation from being adopted: Nelida worked with the wrong housewives of the village, because she ignored the importance of interpersonal relationships and social networks within that milieu; she did not work with the village opinion leaders, who could have activated local networks to spread the innovation; rather, she concentrated her efforts only on a few, socially excluded housewives. Furthermore, Nelida herself was perceived as an outsider by village housewives, in particular by lower-status ones (Rogers 1995: 1–5).

2 The second example deals more directly with ICTs: it is the case of the diffusion of the so-called 'QWERTY' typewriter (and computer) keyboard, named after the first six keys on the upper row of letters. The QWERTY keyboard is inefficient and awkward; it was invented in 1873 in order to slow down typists, since when they struck two adjoining keys too fast, often these jammed. The QWERTY keyboard, thus, allowed early typewriters to work satisfactorily by placing letters on the keyboard in such a way as to cut down on hasty jamming of two keys. In 1932, when the QWERTY design was no longer necessary, August Dvorak invented a much more efficient keyboard whose design was informed by the results of a series of time-and-motion studies. Nonetheless, the Dvorak keyboard did not spread at...

Table of contents

- ROUTLEDGE INTRODUCTIONS TO MEDIA AND COMMUNICATIONS

- CONTENTS

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- SERIES EDITOR’S PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- FIGURE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- ABBREVIATIONS

- INTRODUCTION

- 1 THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF THE INTERNET

- 2 COMPUTER MEDIATED COMMUNICATION (CMC)

- 3 HYPERTEXT

- 4 WEBSITES AS COMMUNICATION

- 5 CONCEPTUALIZING USERS OF THE INTERNET

- 6 INTERNET

- CONCLUSION

- FURTHER READING AND RESOURCES

- REFERENCES

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Internet by Lorenzo Cantoni,Stefano Tardini in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Computer Science & Computer Science General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.