![]()

1

Introduction to Learning Intervention

Everything we do with children acts to intervene in their development and learning. Such action begins with parents using activities of talking, reading or singing to a baby growing inside the womb. As soon as a baby is born people interact and this is the beginning of social interaction as intervention in that person’s lifelong learning journey. This activity develops into formal instruction that is provided in education settings.

Some of the people intervening in children’s development and learning take this role by virtue of their relationship as parent, grandparent, auntie or uncle, or older brother or sister of a child. Others are professionals, with tertiary education and qualifications and accreditation that have prepared them for formal, strategic intervention in students’ lives. The distinction between these two very different, yet similar, roles is highlighted through the definition of intentional teaching (Leggett & Ford, 2013) by which teachers activate and nurture active learning for young children and which is used to distinguish early childhood education from child minding.

In order to ensure that all students have the opportunity to benefit from such intentional responsive teaching education professionals undertake formal intervention of varying kinds. In this book we will explore what learning intervention is in formalised educational settings. We show how such intervention needs to be flexible and adaptable in order to respond to the variability of learning needs of individuals or groups of learners. Intervention is not doing things to people. It is not coercive, nor is it training. Instead it is about using expertise in child development and learning to provide opportunities for learning that best meet the learning needs of students at any particular time. It is also about using interactive, adaptive strategies that help the learner to make the most of the learning opportunities.

In particular, we will consider two processes of learning intervention, responsive teaching and educational casework, which have different perspectives: the former has a focus on a classroom of individuals, and the latter a focus on individuals who are members of a class. These processes are examined in detail in the next chapter.

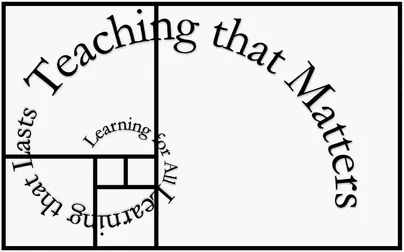

FIGURE 1.1 Sustainable learning

Source: Graham, Berman & Bellert, 2015.

Sustainable learning

Learning intervention supports sustainable learning – learning for all, learning that lasts and teaching that matters (Figure 1.1; Graham, Berman & Bellert, 2015). Learning is holistic, and an important part of the development of learners so they can fully participate in life culturally, physically, psychologically and spiritually – and in connection to community (Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, n.d.). As far as possible, all of us use the capabilities we develop as children and adolescents to live flourishing lives marked by positive emotions, positive relationships, engagement, meaning and accomplishment (Seligman, 2011). We alter, refine and renew the capabilities throughout our lives to match the contexts within which we are living, working, relating and learning. Sustainable learners are those who are able to continue to learn and adapt throughout their lives by drawing on their capabilities for learning.

Learning for all

As education has become more formal and teaching has developed into a profession, the community responsibility for children’s learning has changed somewhat. The natural human interactions of teaching and learning that are embedded in our families and their cultural and social worlds have been transformed into formal education. The role of teaching is now sometimes seen to be exclusive to those who have met the qualification and registration requirements of our society, and learning intervention is implemented with considerable structure and contrivance. This book is about learning intervention within that education system, that responds to the learning needs of all students through the professional activity of not only classroom teachers, but also other professionals with deeper or different expertise who can contribute to strengthening what is happening in teaching and learning in contemporary inclusive schools. There are a number of important considerations in relation to inclusive schools that are presented here as a foundation for considering professional practice in learning intervention.

Groups of learners in schools are increasingly diverse and display a large range of achievement even across what were previously thought to be homogeneous groups of students of the same age. Schools also include students who have disabilities or who experience significant learning difficulties. The enormous variability in the development of humans needs to be recognised and responded to by those who are teaching. The diversity of human development and of learning means that not all our students will follow expected patterns or typical rates of learning, and therefore inclusive education systems need to be responsive to the needs of all learners.

In a similar way, curriculum has increasingly recognised that learning is not just about fixed bodies of knowledge and skills. Instead, opportunities to learn have become more diverse and interactive over time, allowing learners to respond actively and authentically to teaching. Whereas once all students were expected to respond in the same way by sitting examinations or listening and then producing short answers or essays in particular formats, we now accept a range of responses that demonstrate learning.

Increasingly, responsibility is being passed to students to manage their own learning and behaviours in classrooms. Teacher-work is less about controlling responses, although the skills of establishing behavioural expectations and maintaining them are still integral to good teaching. Instead, teachers are proactively seeking to increase students’ responsibility for their own behaviour and learning.

Learning that lasts

Knowledge and skills taught in schools have changed considerably from the fixed body of knowledge of the early 20th century, due to the explosion of knowledge and the constant, almost overwhelming, access to information that we now encounter. The focus of education has, subsequently, turned towards learning processes and capabilities because these can be used as needed across the curriculum to approach many different types of learning tasks.

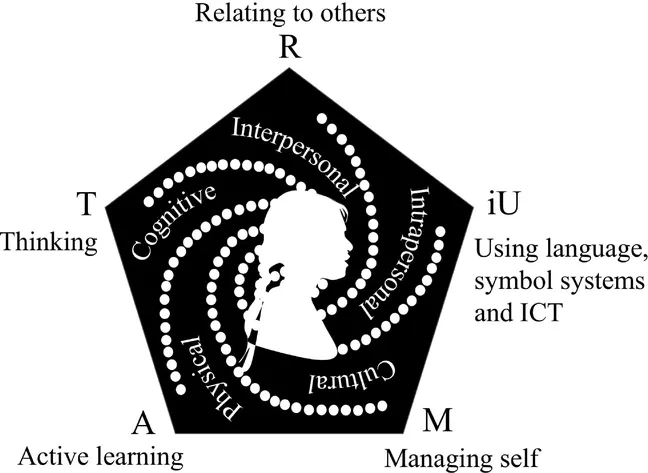

The challenge for educational settings is to provide students with the foundation for managing their lives in a dynamic world. As an example, a recent advertisement stated that students currently entering the workforce could expect to have up to 30 jobs in a lifetime. This means an almost constant demand to adapt to new work circumstances and roles. ‘Learning that lasts’ is learning for life and learning for the future, the demands of which are not yet known. As it is impossible to predict what jobs, careers and pastimes are going to be popular in the future, schools cannot provide opportunities to learn all future knowledge and skills. What can be provided, however, is a focus on developing the psychological processes that humans need in order to continue to learn and adapt to whatever the future holds. In this book we are using the ATRiUM model (Figure 1.2; Graham, Berman & Bellert, 2015) of human development and capabilities for learning in our consideration of responsive teaching and educational casework for learning intervention.

FIGURE 1.2 ATRiUM capabilities and five dimensions of human learners

Source: Adapted from Graham, Berman & Bellert, 2015.

Sustainable learning involves all five of the ATRiUM capabilities: active learning, thinking, relating to others, using language, symbol systems and ICT; and managing self; and, draws on the adaptability and flexibility of humans in an increasingly uncertain world.

Teaching that matters

Teachers have the enormous responsibility of contributing to the development of the processes of human functioning for each of their students so that individuals can become successfully intelligent, that is, able to apply analytical capabilities practically, creatively and with wisdom throughout life (Sternberg, 1997; Sternberg & Grigorenko, 2007). When learning is visibly at the centre of everything that goes on in the classroom, teachers and students sustain each other’s learning. Learning in the 21st century needs to be not only lifelong, but also ‘life-wide’, with a focus on the capabilities of individual learners as they engage and interact with their wider world and respond to the demands of new careers, new technologies, cultural shifts, and rapid and unpredictable change.

FIGURE 1.3 For many learners, teach does not necessarily mean learn

Inclusion of all learners in a classroom depends on each student’s learning needs being met, and on learning happening through effective teaching. Although many learners will achieve academically irrespective of the teaching provided, it is a teacher’s intentional activity focused on activating learning that makes a difference for many students; skilful teaching matters enormously to learners who experience any sort of difficulty. The sophisticated responsive work of professional teachers really makes a difference for learners, and it is this type of teaching that is the focus of this book.

There is a meme that shows a reflection of the letters in ‘Teach’ that can be read as ‘Learn’, as in Figure 1.3. The calligraphic design, that needs distortion to work, reflects the idea that to teach is to activate learning and that these are two sides of the one activity. This idea of teaching and learning depending on one another is ancient and is evident in a single word meaning both teaching and learning in some languages, for example, ‘ako’, in Te Reo Māori (language). These calligraphic and linguistic blurrings of ‘teach’ and ‘learn’ are significant because until teaching translates into learning, it is not effective teaching.

Instead of these activities reflecting each other, in this book we use the notions of overlap and dependence. Learning can happen independently of teaching. Many students learn irrespective of the teaching they receive, as they have effective learning strategies and have access to opportunities to learn. However, a key issue for learning intervention is that, for many students, learning will not happen unless the teaching responds to their specific learning needs.

Intervention for sustainable learning within families

While our focus in this book is the formal learning intervention undertaken by education professionals, it is important to remember the role of informal learning intervention, particularly within the family. Traditionally teaching to support child development occurred in families and extended family communities, drawing on adults and older children to support the learning of all younger children. Group responsibility is evident in this situation and the child draws on the teaching of a range of people. When one teacher is not immediately available there are others to engage with. Such teaching in everyday life is often incidental rather than deliberately planned, but in many ways it is naturally intentional, as parents and older relatives consciously engage with a view to teaching for everyday learning.

We are social beings and we strive to engage socially and to have influence on others through our interactions. This influence includes sharing new information and new ideas, prompting higher-order thinking as well as activating and facilitating a thirst for new knowledge and skills. This focus on the whole child and on capabilities for life is inherent in the teaching that happens in informal settings, in homes and communities as parents and family members work to strengthen capacities that are needed for life.

Much of the teaching of the capabilities for sustainable learning is grounded in the transmission of family culture, often with parents teaching in ways they have been taught, and using family expectations around behaviour and learning. At the same time, older family members engage in their own lifelong learning journeys, while they become involved in the learning journeys of their children, grandchildren, nieces and nephews. In contrast to previous beliefs, adult humans are not fully mature people who have finished learning. Instead, they continue to learn as they engage with younger family members in teaching and learning exchanges.

All of us experience childhood learning as children, and then again as parents or older relatives. Our children’s lives are the second period of time in which we intensively experience child development and practise teaching. Many parents say they wish they knew then (when their children were young) what they know now about child development and learning. But that is never the case, and so it is important to have multiple generations of people supporting the development and learning of young people where possible. Indigenous models of child rearing that explain traditional practices (e.g., Poananga, 2011) emphasise this reliance on multiple generations to support young people’s learning.

Families teach children foundation capabilities for what is needed throughout their lives by shaping expectations and providing opportunities for the child to grow as a complex multidimensional (e.g., cultural, cognitive, physical, intrapersonal and interpersonal) being. Families foster the development of skills and knowledge within all of the ATRiUM capabilities (Graham, Berman & Bellert, 2015) described above, so that children become active learners, thinkers, socially related people, competent users of language and symbol systems and ICT, and managers of their lives.

Active learning

Adults who continue to learn actively in everyday life model sustainable learning (Graham, Berman & Bellert, 2015) and lifelong growth mindsets (Dweck, 2006) for their children. Families can establish and nurture expectations around sustainable learning that influence the learning of their children at school. They draw the younger members of the family into learning activities, and perpetually learn together. For such families, this love of learning becomes a key dimension of everyday life, of holiday experiences and the stuff of career pathways. They actively pursue learning opportunities for their children, follow curiosity and interest, and spend leisure time at places that promote learning. Based on an understanding of the impact of experience in social and cultural settings for human development and learning, such strategic travel and physical, musical and social activities are inherent to the...