![]()

Part I

Entering the Field

Plate 2 Madi (left) and Sidi Mohamed uld Sanad, my research assistant (Niamey)

![]()

1

Coming into the Azawagh

The [Arabs of the Azawagh] are good herders and also excellent traders; their caravans go all the way to Touat [in Algeria] to bring animals and to exchange mainly ostrich feathers and skins … for gandouras [men’s robes] and blankets. They maintain very cordial relations with the French authorities, but retain nonetheless a pronounced spirit of independence that pushes them to live apart in the most isolated pastures of the Azawagh.

-Col. Maurice Abadie 1927: 153

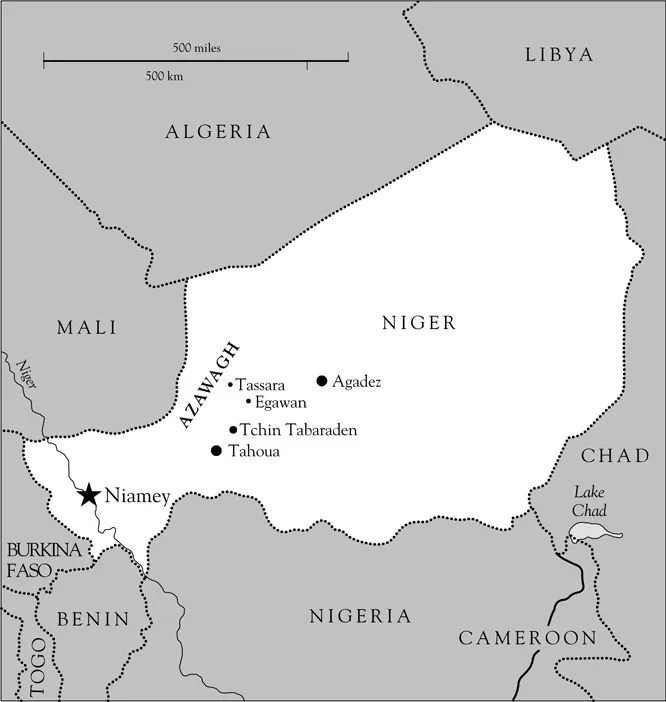

In a mostly empty spot in the center of the map of West Africa lies the Azawagh region of Niger, a sparsely populated stretch of savanna where the gently undulating grasslands of the West African Sahel meet the drier, harsher landscape of the Sahara desert proper. It is roughly the size of Austria but is home to only about 85,000 people, predominantly from four ethnic groups. For two years in the mid-1980s and for fifteen months in the early 1990s I lived in this region, first as a Peace Corps volunteer in a town of approximately 5000 people, and then in a village of about 700 where I carried out the fieldwork on which this book is based.

The Azawagh

The landscape against which Azawagh Arab women pack their bodies until overflowing with plentiful, moist fat and veiled folds of allure exhibits anything but those bountiful traits to the outsider. Desolate, flat semi-desert under a giant dome of blazing sky, the corner of Niger where most Arabs live is a land of sparse grass and occasional spindly, thorny acacia trees.1 However bleak northwestern Niger appears to one from greener climes, to Azawagh Arabs the terrain that they consider earth’s basic form is rich and diverse. The dunes that to me were unremarkable, identical swellings rose as mountains to the men I traveled with, and a tree that I would hardly

Map 1 The Azawagh region in Niger

notice was a looming landmark. The seemingly meager vegetation provided not only a smorgasbord of grasses for animals, but a well-supplied pharmacy as well. Once when out on a day trip in the desert, an old man and I sat under a tree while he identified no fewer than eleven tiny plants sticking up out of the soil, each no more than an inch high, all more or less indistinguishable to me. He explained carefully which animals ate which, and how each plant benefited or harmed them. Similarly, women could list dozens of local plants that were used to treat human illnesses, explaining in detail how the leaves or bark could be cooked, ground, or combined with other ingredients to soothe all manner of complaints, from constipation to scorpion bites.

Far more ubiquitous than vegetation, sand comes in several varieties: large-grained lḥse›, deep loose ramle, hot azeyz. As ubiquitous as the sand is the wind. Though harshest before rainstorms and in the winter season, wind knocks against the landscape incessantly in all seasons. The gusts pick up in the vast desert reaches and trip across the plains, tossing up sand, flapping the tent sides, and constantly blowing this researcher’s hair into unbecoming chaos in the absence of the oil and heavy braids that make up the stiff hairstyles of Arab women. From December to March, the winds carry so much sand that the world turns into an anemic yellowish-gray haze for weeks on end. Like sand, the wind comes in many varieties: there is the cool amerūg, the hot irl̅fi, and the zowbʿaya whirlwinds.

While the Azawagh Arabs seem little bothered by the wind in the way I was – the endless, unsettling irritation and the fine grains of sand it deposits in food, ears, and books – they are concerned by the less visible and ultimately more potent ills that it can bring. As a more general term, wind is a metaphor for, even the embodiment of, spirits and forces of evil. To keep such forces at bay, people often quietly recite a prayer as a whirling funnel of dust hurries across the desert. Wind is also the bearer of “heat” and “coldness,” forces that reside in bodies and the world and that must always be kept in balance. Like gravity or an electromagnetic field, the wind and the unseen forces it carries silently and invisibly enter all substances, connecting people to the world around them.

This windswept corner of Niger is today home to a patchwork of distinct ethnic groups, comprising a metropolitan desert world of different languages and customs, though all the groups share a faith in Islam. Historically, the dominant ethnic group in the region has been the Tuareg, a better-known Saharan nomadic group whose indigo-turbanned men and silver-bejewelled women have appeared in movies like The Sheltering Sky and Beau Geste. Like Azawagh Arabs and most other peoples in Niger, the Tuareg used to have a slave caste known as the Bouzou, who are a populous ethnic group in their own right, even as some seem to be assimilating to sub-Saharan black African ethnic groups in the south. Numerous cattle-raising, nomadic Wodaabe Fulani have also long drifted in and out of the zone. The Wodaabe, a group that became Muslim only recently, have been much photographed by outsiders and have been featured in picture books and calendars of Africa, highlighting the way men bedeck themselves in jewelry, paint their faces, and dance before young women to attract lovers. More recently, increasing numbers of Muslim Hausa and Zarma, sub-Saharan black groups that dominate Niger politically and numerically, have arrived in the north as civil servants, government officials, and traders.

The Azawagh has known fighting at several points in its recorded history, beginning with the violent French colonization of the Tuareg at the start of the twentieth century. Since the 1980s when the Azawagh and other Tuareg regions of Niger were hard hit by drought, the Tuareg have waged an on–off guerrilla war for more power and independence within Niger. Azawagh Arabs and Tuareg have raided each other periodically throughout history as the Arabs encroached on Tuareg lands, and simply because raiding generally has been something of a subsistence strategy in this part of the world. Although Arabs and Tuareg were at peace for much of the twentieth century, violence between the groups intensified again in the early 1990s in the context of Tuareg revolts against the government, since the Arabs own vehicles, guns, and other resources that the Tuareg need. This is, at least, the Arab view of matters. There have been so many raids and counter-raids over the years that both sides are no doubt equally guilty of prolonging the fighting, in which many lives have been lost.

The Azawagh Arabs of Niger are concentrated in the north of the region. Their de facto capital is the village of Tassara, my fieldwork site, but a number also live in the county capital, Tchin Tabaraden, where I worked as a Peace Corps volunteer. Both settlements came into being only in the last fifty years and are the products of outside intervention, not indigenous settlement alone. Tchin Tabaraden was established by the French in the middle of the century, and Tassara by the Nigerien government in the 1970s, both essentially as places where the government could station its leaders, schools, and army, in addition to more welcome health clinics and water stations.

Those who live in the northern reaches of the Azawagh make their peace with desiccating heat in the spring, rainstorms of biblical proportions in the brief summer, and chill nights and stinging windstorms in the winter. The sky arches always overhead, huge and distant and endless. There is a desolate beauty to the landscape, and amidst the impermanence of land, air, and people, a kind of stillness and absoluteness that is deeply calming. As bone-thin cows, camels, sheep, and goats scrounge lazily for sustenance on the vast reaches of sand, their owners engage in endless travel to make their trade profitable, retain their autonomy, and remain on land they consider their own and profess to love. Despite the increasing temptations of more urbanized life to the south, the Azawagh Arabs have stuck to this remote region, remaining satisfyingly beyond easy reach of first French and now Nigerien officials, extracting a living from the seemingly most ungenerous of pastoral landscapes, and maintaining a desired nearness to the Arab world to the north.

Who are the “Azawagh Arabs”?

The issue of just who the Azawagh Arabs are and how to label them is a textbook case of a basic ethnographic truth: peoples do not always come in neatly bounded units with a name all agree upon, even if the modern world of nation-states has led us to believe that this should be so. Descended from Arabs of the Middle East, the people I studied speak a dialect of Arabic, and consider themselves to be simply Arabs. Arabs from the Middle East, however, would not consider them “pure” Arabs and indeed, according to histories written by outsiders, there has been considerable intermarriage with non-Arab peoples over the past five centuries.2 Their language and culture align them less with the Arabs of northern Africa and more with the Moors of Mauritania, but the Arabs of Niger do not see themselves as such. So who are they and by what name should they be called here?

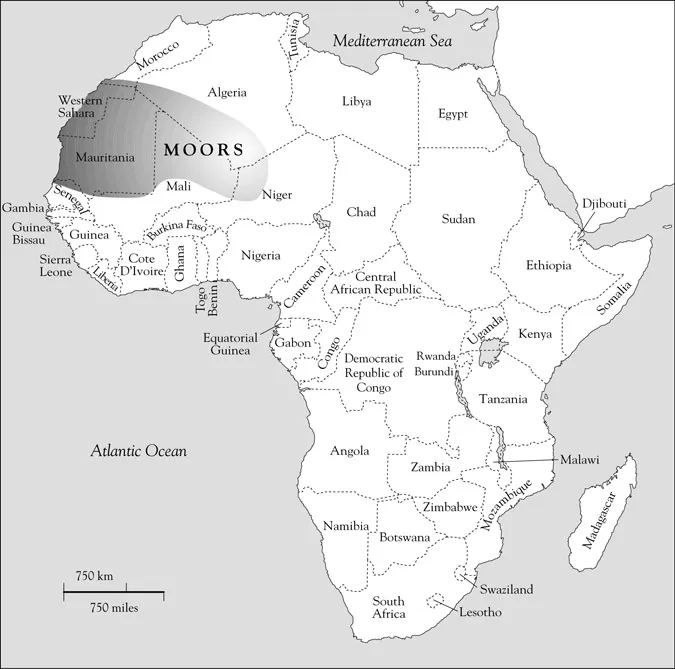

While the people of northwest Niger whom I studied refer to themselves simply as “Arabs” (ʿArab), culturally, linguistically, and historically they belong to a group of Arabic speakers across the western parts of the Sahara desert known most commonly in the modern West as Moors. Moor society coalesced between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries in northwestern regions of the Sahara out of the mingling and intermarriages among local Berbers (the inhabitants of North Africa before the Arabs came), newly arrived Arabs, and sub-Saharan Africans (Webb 1995: 15). Today they number approximately one million and make up the predominant population of Mauritania; they also live in the rural margins of Mali, southern Algeria, and Niger, and are closely related to the predominant ethnic group of Western Sahara. (See Map 2, page 18.)

The “Arabs” of Niger represent the easternmost tip of this group, number between 15,000 and 20,000,3 and speak a form of Arabic they call Galgaliyya, a variant of the Hassaniyya Arabic spoken in Mauritania. Oral traditions and old Arabic documents relate that about a century ago they moved east into what is now Niger from the area of present-day Mali, and for several centuries before that resided further north in what is now Algeria. Mostly nomadic until the early 1970s, more and more Azawagh Arabs are now settling in small desert communities and, occasionally, in larger towns. Their increasing settlement is due most directly to droughts in the early 1970s and 1980s that forced people into villages to get water and food, where they then stayed, enjoying the nearness to water (from pumps), relatives, and certain material goods.

Across the huge swath of land where Moors, including Azawagh Arabs, reside, they share devotion to Islam, belief in Arabian roots, similar dialects of Arabic, an economy based on herding and trade, a caste-like social structure that leaves much hard labor to former slaves, and many similarities of dress, poetry, ritual practices, and, not least, bodily ideals. In many rural areas of the Moor world the corpulent female aesthetic is still prized, and the fattening of girls continues to take place in parts of Mauritania and Mali (Tauzin 1981, 1987, 1988; Amidié 1985; Brewster 1992; Hildebrand et al. 1985) as well as in Niger.

Even if Azawagh Arabs are in some senses essentially the same people as the Moors of Mauritania, the term “Moor” is not particularly

Map 2 The approximate location of Moors in Africa

appropriate to the Nigerien context. First and foremost, the Arabs of Niger do not consider themselves one with the inhabitants of Mauritania. Second, the term “Moor” is of European derivation (from Latin, referring to the people of North Africa) and is not used in the local language anywhere in the “Moor” world, as far as I know. Third, the term also has a long history of European usage to refer to Berber and Arab peoples of other times and places, for example the Moor invasion of Spain and Othello the Moor, where it means Berber North Africans. The term is therefore a confusing one to use for the “Arabs” in Niger.

Since not only they themselves but all the other ethnic groups around them also called the Nigerien Moors simply “Arabs,” this term is the one most sensitive to local habits. The simple “Arab,” however, is too general and misleading in the wider context I write within. Therefore I felt compelled to find a more satisfactory ethnic label that would work both for those I write about and for myself and Western readers. When I asked the people themselves how I should refer to them, I learned a great deal about their self-image from their answers: they suggested that I call them “Yemeni Arabs” or “Saudi Arabs,” harking back to their putative roots in Yemen and Saudi Arabia as companions of the Prophet Muhammad. Rejecting the potential complications of these admittedly intriguing suggestions, I have finally chosen the neologism “Azawagh Arabs,” after the region of Niger where they live, to refer to the people whom this book concerns, a name to which people I spoke to about it acceded.

There is one additional aspect of Moor and Azawagh Arab society that complicates the process of group naming, and that is that they are caste societies. Among Azawagh Arabs there are three main castes: (1) the “white” or “free” Arabs; (2) the former slave caste, called ḥaraṭl̅n; and (3) the small artisan caste, also called blacksmiths in Western languages. The hierarchy of these castes is imagined in terms of skin color, with the former slave caste termed “black” and the artisans considered of intermediate skin color, though in reality there are very dark-skinned “white” Arabs as well as very light-skinned “black” Arabs. What more accurately distinguishes the castes is descent, status, and a lack of intermarriage across caste lines.

Even though slavery has been officially outlawed by the Nigerien government since 1960 and even though all “white” Arabs now pay the freed slaves to work for them, remnants of master–slave relationships still exist. Óaraṭl̅n still fetched water and did small tasks for their former masters at their bidding, and, in return, the former masters gave gifts to their former slaves on holidays and helped them in times of need. The segregation was also perpetuated geographically; the ḥaraṭl̅n all lived on the north side of the town where I did fieldwork, and the “white” Arabs lived in the center and at the southern end. Even as one could see the former master–slave relationship slowly evolving into something more akin to ranked ethnic distinctions, the racialized inequalities of the situation were often uncomfortable for a Westerner.

The complexity of the caste situation will be explored further in chapter 5. For now, I will note that the existence of slavery has been crucial to the persistence of fattening, which is only possible for girls who do not have to do household work. Indeed, when I asked “white” Arab women who were not fattening why they had stopped, a not infrequent answer was, “Our slaves have left; how can we fatten?” The ḥaraṭl̅n had not themselves taken up the practice of fattening their daughters, but they nonetheless appreciated and strove for the same aesthetic.

Peace Corps prelude: Tchin Tabaraden

My initial contact with Niger, and with Azawagh Arabs, came in 1985. That year I joined the Peace Corps as a health volunteer and was sent to Tchin Tabaraden, a town of about 5000 people. A sprawling, dusty place at the end of a long gravel road, Tchin Tabaraden consists of a grid of sandy lanes lined by adobe walls, behind each of which stretches a yard of more sand with a mud house or tent. Of the many ethnic groups in the town, the Azawagh Arabs were the least visible, not because of their small number but because the men dress in the same flowing robes and turbans that the Tuareg wear and are generally fluent speakers of the Tuareg language, Tamajeq, while Arab women, wh...