eBook - ePub

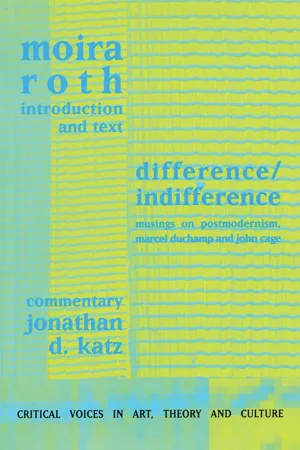

Difference / Indifference

Musings on Postmodernism, Marcel Duchamp and John Cage

- 202 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Difference / Indifference

Musings on Postmodernism, Marcel Duchamp and John Cage

About this book

First Published in 1999. For the first time gathered together in book form, here are the influential writings of Moira Roth-articles, lectures, and interviews-on the two men who for so long embodied the very spirit of the avantgarde, Marcel Duchamp and John Cage. For almost thirty years Duchamp and Cage, who seemed to live on the border of modernism, and later, of postmodernism, alternately have fascinated, irritated, inspired, and daunted the author. Since her initial engagement with Duchamp and Cage in the early seventies, Roth increasingly focused on the work of many American artists-primarily women-only to return to Duchamp and Cage intermittently. At first, they were an inspiration for her writing and teaching. However, as they transformed themselves into classical figures, she came to reconsider and re-evaluate them. This collection offers a wide variety of literary forms-analytic, diaristic, art historical, and autobiographical-all of which Roth has used in her work. Collectively these writings form the subject of compelling and unique critical exchange between Moira Roth, who holds the Trefethen Chair of Art History at Mills College, Oakland, and Jonathan D.Katz, who is Chair of the Department of Gay and Lesbian Studies at City College, San Francisco.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Difference / Indifference by Moira Roth,Jonathan D Katz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

part one

ESSAYS BY ROTH, 1977, AND

COMMENTARY BY KATZ, 1998

“Marcel Duchamp in America: A Self Ready-Made,” Arts 51, no. 9 (May 1977): 92–96.

An article in which I place Duchamp, a French symbolist dandy and hermetic scholar, and Rrose Sèlavy, a femme fatale, in modernist America, and discuss the roles Duchamp’s art and per-sonae inventions played in American art history. The May 1997 issue of Arts was devoted to New York Dada.

marcel duchamp in america

a self ready-made

Cabanne: You were a man predestined for America.

Duchamp: So to speak, yes.

—Pierre Cabanne,

Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp

Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp

He was twenty-nine years old and wore a halo… . He was creating his own legend. … At that time, Marcel Duchamp’s reputation in New York as a Frenchman was equalled only by Napoleon and Sarah Bernhardt.

—H. P. Roché,

“Souvenirs of Marcel Duchamp”

“Souvenirs of Marcel Duchamp”

The New York that Duchamp first visited in 1915 was the New York of Diamond Jim Brady, a millionaire best known for his eating habits and his diamonds. He sported diamonds on his cufflinks, shirt, and suspender buttons and, according to rumor, had diamond bridge work in his mouth. When questioned on this display he would answer, “Them as has ‘em, wears ‘em.” His eating style was equally lavish: he would consume three dozen oysters, just as a starter. Upon settling down for a meal, he would carefully leave four inches between his stomach and the table so that “when I can feel ‘em rubbing together, I know I’ve had enough.”

Fritz Lang first saw the skyline of Diamond Jim Brady’s city in the early 1920s. This vision inspired a story about a city of the future, with high-rise office buildings, aerial freeways, and suspended pleasure gardens. The city of Metropoliswas a spectacular example of the futurist dreams that New York excited in its visitors. From the vantage point of Europe, this futuristic and vulgar image of New York overshadowed its other aspects of sophistication and elegance. Obviously, New York possessed an educated and well-mannered upper class and artists aware of emerging new directions in art. But this was not basically what its European visitors knew or wanted from New York.

On June 15, 1915 this futuristic and vulgar city received another visitor, the fastidious Marcel Duchamp, an artist profoundly rooted in nineteenth-century thoughts and types. Yet it was to be America, not France, which first created and then maintained Duchamp’s fame, beginning with the notoriety of his Nude Descending a Staircase in the Armory Show. From 1913 onwards, the relationship between Duchamp and America became mutually supportive, positive, and intimate. It was America that finally gave Duchamp his first major retrospective exhibition (1963) and where virtually all his works are located, and it was America that provided a home for Duchamp off and on since 1915, and where his iconoclasm was immediately incorporated into the history of American modernism.

During the period of his early visits, New York supported in many ways the expansion and elaboration of earlier Duchamp ideas which had been formulated in prewar Europe. The Bicycle Wheel was made in 1913 Paris, but the Readymades were only named as such in 1915 New York and were exhibited there for the first time in 1916. The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) was conceived a few years earlier, but only in New York was the work actually begun in 1915. Most significantly, it was the New York Dada group that watched and protected Duchamp’s personae experiments and performances, which amplified his life style, his art, and his definitions of himself as an artist.

New York in 1915 was a modern city in a way Paris would never be. Duchamp needed the freedom and approval of such modernity. This context and this city provided Duchamp the license to explore two psychological types, the dandy and femme fatale. To characterize Duchamp through these two nineteenth-century and essentially European types points to the amazing juxtaposition of two worlds, old and new, when Duchamp and modernist America took to each other so warmly.

Common to both the dandy and femme fatale are psychological traits of distancing, mystery, and moral indifference— all of which Duchamp possessed in abundance. It is hard to know whether these characteristics are innate or assumed, assumed as theatrical modes of self-presentation to the public or perhaps as self-preservation devices to mask private and less confident selves. What is clear is that both the dandy and femme fatale are dependent upon an audience and a particular form of adulation, or at least, public recognition. The archetypical forms have a long history but literary discussions of the types are generally confined to the nineteenth century. Duchamp grew up in the symbolist period, a time when the final extravagant, often bizarre flowering of these two types occurred.1

Duchamp is generally described as a modern day dandy in appearance and temperament. To see the dandy merely as a man meticulously elegant in dress and manners is to misunderstand that, at least in Charles Baudelaire’s eyes, these were only the outward manifestations of a state of mind. For Baudelaire, the dandy was a psychological type, a type obsessed with a “cult of self” who used elegance and aloofness of appearance and mind as a way of separating himself from both an inferior external world, and from overt pessimistic self-knowledge.

The lifestyle of the dandy had been lived out and chronicled before Baudelaire but it was Baudelaire’s classic 1863 essay, “The Painter of Modern Life,” which crystallized the concept of the dandy. It is interesting that Baudelaire not only dealt with the dandy in the context of art and modernity, but also, more to our point, he stressed that the dandy’s first concern was with his own character rather than with his art or the society in which he lived.

Also, in his essay, Baudelaire talked about the flâneur, the observer who strolls through the crowd but is not really part of it. The flâneur is a key aspect of the dandy’s psychology, for the dandy’s elegance demands an appreciative public. The context of the crowd makes his own superiority all the more obvious, at least in his own eyes. Also, for the flâneur to live apart as a recluse might force him into an intolerable introspection and psychological confrontation with himself. He chooses rather to stroll casually through the world, the dandy flâneur constantly preserving his psychological distance and protecting his intellectual superiority.

Much of Duchamp’s imagination during his first 1915–1918 New York visit (and his two later visits of 1920–1921 and 1922–1923) focused upon a conscious expansion and transmutation of his personality and intensification of the dandy’s “cult of self” both in his real life behavior and in his various artistic per-sonae culminating in Rrose Sélavy. For a European flâneur New York City was a perfect place to parade in and yet not be part of. The readymades, too, benefited from an American setting where their alien nature was more prominent than if they had publicly emerged alongside collage and assemblage productions of Cubist Paris.

Within Duchamp the dandy, in 1915, there is another element of his personality, namely that of the femme fatale. A dandy might have intimidated a New York audience, he would never have charmed it. Two qualities in Duchamp are mentioned repeatedly by contemporary observers: his seductive charm and physical beauty and his psychological distance and indifference, a combination which is key to the phenomenon of the femme fatale. She is involved in the seduction of others but never submits herself to seduction.

Greta Garbo, certainly one of the most famous femme fatales of all, has been described in a way that recalls the Duchamp of 1915:

As attractive to women as to men, At the same time, she seemed emotionally and philosophically wary, detached, passive. [Garbo’s] face… had an extraordinary plasticity, a mirror-like quality; people could see in it their own conflicts and desires.2

There is an astonishing similarity between Garbo and Duchamp (posed as Rrose Sélavy) in their beauty and remoteness: staring out of their photographs, with their hands idly protecting them, they both project an image of utter aloofness. In both portraits there is an inpenetrable impassivity. It is impossible to tell their thoughts but perpetually intriguing to speculate.

The fact that Garbo is a movie star literally relates her on another level to Duchamp and to the long tradition of artist “stars” beginning with Leonardo, if not earlier. These artist-stars, and Duchamp stands prominently in this category, project a glamour which seduces their audience into an almost obsessive attention to their presence as artists and sets up a condition of uncritical adulation of their art.

From the moment of Duchamp’s arrival, this star charmed both the newspaper reporters who met him at the dock and a more elitist New York intellectual circle. Neither had met or really knew the prewar Parisian Duchamp. Whatever their expectations, the Duchamp they encountered in New York was a new creation of personality, a theatrical and seemingly far more outgoing character than Europe had known. In 1912, after the debacle with his brothers and their fellow cubists over the exclusion of the Nude from their 1912 avant-garde show, Duchamp had deliberately withdrawn himself from close commitments to artistic groups. He lived a life of seclusion. Yet in New York, he was to shine as a central presence in the Arensbergs’ salon. Duchamp has described this Paris period of 1912–1915:

I knew no one in Paris… I stayed very much apart, being a librarian… I had no intention of having shows or creating an oeuvre, or living a painter’s life.3

Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia had met Duchamp in 1910, and confirms Duchamp’s recollections of those years:

In that period [Francis] Picabia led a rather sumptuous, extravagant life, while Duchamp enclosed himself in the solitude of his studio at Neuilly, keeping in touch with only a few friends and [living by] a discipline that was almost Jansenist and mystical.4

The astonishing and abrupt transformation of Duchamp’s character in New York was witnessed by Picabia’s wife, when they arrived in America, shortly after Duchamp’s first appearance there:

We had found Marcel Duchamp perfectly adapted to the violent rhythm of New York. He was the hero of the artists and intellectuals, and of the young ladies who frequented these circles. Leaving his almost monastic isolation [of Paris], he flung himself into orgies of drunkenness and every other excess. But in a life of license as of asceticism, he preserved his consciousness of purpose: extravagant as his gestures sometimes seemed, they were perfectly adequate to his experimental study of a personality disengaged from the normal contingencies of human life.5

His compatriot and friend H. P. Roche had similar memories of Duchamp’s new manner. Upon their first meeting in New York, Duchamp immediately swept Roché off to a costume ball where Roche watched admiringly as the women swarmed around Duchamp. Roche recalled another evening which ended up with Duchamp drunk, balanced on the edge of the elevated with a young woman.6

Duchamp was a highly controlled and contrived individual. If his personality and lifestyle seemed to change drastically upon arriving in New York, at least some of the changes were conscious. Later Duchamp himself was to admit to “this fabrication of his personality,”7 and acknowledged the influence of a model, Jacques Vaché, the Dada dandy so admired by Breton.

Duchamp’s appearance in 1915 New York was the appearance of a new type of artist in America, a type novel and alien in a country dominated by the protestant work ethic. Also, New York had been virtually untouched by the symbolist movement, Duchamp’s breeding ground; such strange artist-priests as Mallarmé simply did not exist in late-nineteenth-century America. The sense of a new type of artist was picked up clearly, though simplistically, in the first published reaction to Duchamp’s visit. Here, the surprised journalist noted:

He neither talks nor looks, nor acts like an artist. It may be in the accepted sense of the word he is not an artist.8

This September 1915 article, a neat piece of American typecasting of Duchamp, bore the title, “A Complete Reversal of Art Opinions by Marcel Duchamp. Iconoclast.”

Duchamp elegantly enacted for his New York audience the dandy’s aversion toward excessive commitment or obvious effort. Later Georges Hugnet spoke of Duchamp’s work in terms of “the relaxation of a brilliant dandy.”9 Duchamp, the artist-dandy, comes out most clearly in his verbal responses to art and in the readymades, which, at their best, are brilliant shifts and gestures of the mind rather than objects dependent upon physical labor. Duchamp did devote much labor and almost obsessive attention to his Large Glass during these early New York visits. Yet, The Large Glass lay for months literally gathering dust in Duchamp’s studio, in preparation of Dust Breeding. And when The Large Glass was broken in 1926 and its cracked state only discovered years later, Duchamp could preserve a carefully indifferent public attitude toward this mishap, could be “amused” by the near destruction of such a major work.

Much that Duchamp said and presented himself as doing, or rather not doing, violently contradicted the prevailing American protestant attitude that everything, including art, must be the result of hard work. For Duchamp, however, art must be a product of the mind:

I wanted to get away from the physical aspect of painting … I was interested in ideas—not merely in visual products. I wanted to put painting once again at the service of the mind.10

Shortly after Duchamp’s new theatrical persona was seen in life, he established another persona, that of R. Mutt. Duchamp selected the urinal in 1917, called it Fountain, and signed it R. Mutt. The exclusion of the Fountain from the 1917 Independent Artists’ show provoked the famous Blind Man text:

Whether Mr. Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view—created a new thought for that object.

Whether Duchamp himself wrote the text, or merely inspired it, is beside the point. The significant point is that here the views of the artist...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Critical Voices in Art, Theory and Culture

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction to the Series

- Foreword: Duchamp, Cage, Roth, and Katz: Accumulative Effect

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Now and Then

- Part One Essays by Roth, 1977, and Commentary by Katz, 1998

- Part Two Interviews by Roth About Marcel Duchamp, 1973

- Part Three Essays and Performance Texts by Roth, 1991—1995, Commentary by Katz, 1998

- Appendix Excerpts from “Duchamp Festival, Irvine, California, November, 1971”

- Notes

- Permissions