![]()

1

THE ORIGINS OF COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY

The ancient theory of eidola, which supposed that faint copies of objects can enter the mind directly, must be rejected. Whatever we know about reality has been mediated, not only by the organs of sense but by complex systems that interpret and reinterpret sensory information.

Ulric Neisser, Cognitive Psychology, 1967

My first aim is to explain why cognitive psychology came about and how it arose from earlier attempts to explain the human mind. In taking this perspective one could go back a long way. Ancient Greek philosophers, for example, had many ideas about the workings of the mind and throughout the history of philosophy there have been concerns about issues that we would now see as the domain of cognitive psychology. However, an account of this nature would be a book in itself and I will confine myself to the last 100 years or so.

Towards the end of the 19th century psychology was dominated by an approach known as introspectionism. The basis of introspectionism was to study mental processes via a method of subjective self-examination. In a typical experiment subjects would carry out a mental act and then report on their inner experiences. A common topic was the nature of mental images; this refers to pictures we all experience in our mind’s eye when we are told to imagine something. Images were thought to be the basis of memory so there was great interest in trying to elucidate the properties of images more clearly. Experiments were therefore conducted in which ‘observers’ formed mental images and then answered a series of questions about what they held in their mind. One question, for example, might concern the clarity of the image at different points and another might concern the intensity of colour. By collecting a sufficient number of these observations it was hoped that some consensus could be reached about the structural properties of mental images (e.g. Armstrong, 1894).

From a scientific point of view introspectionism was doomed to failure because its database was totally subjective. Consider the imagery experiment above: how can we be sure that different people use the same scale to describe their subjective impressions? Thus, what is very clear or highly intense for one person might not be for another person. There is also the problem of observer bias in that questions might be structured so as to elicit particular types of answer.

Therefore, introspectionism was easy to criticise as a scientific approach to understanding the mind. However, although their methods were poor, this does not mean that what the introspectionists chose to study was unimportant. Indeed it is often stated that the most famous of the introspectionists, William James, posed many of the central questions which psychology has to answer (James, 1890). However, these insights were swept aside by the arrival of a new and radically different approach to psychological investigation—behaviourism.

Behaviourism

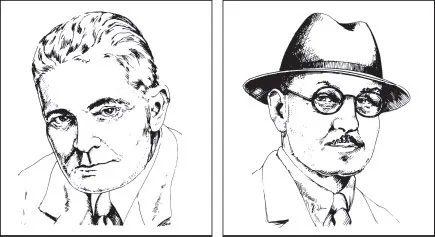

Although he was not the originator, the birth of behaviourism is most commonly associated with John B. Watson. John Watson was a colourful character who argued the behaviourist viewpoint from an extremist position. Essentially, he proposed that psychology should not be based on the accumulation of subjective impressions about mental concepts. Watson’s view was that psychology should be based solely on observable events and that it should divorce itself from mentalistic concepts such as imagery and consciousness because these were unobservable (Watson, 1913). In developing behaviourism, Watson was undoubtedly influenced by two major scientific figures, Pavlov and Darwin.

Pavlov had worked extensively on understanding the conditioned reflex and had shown in a variety of experiments that naturally-occurring responses such as salivation in the presence of food could become associated with previously neutral stimuli such as a bell—a process known as classical conditioning. For Watson this was an ideal situation: here was a learning mechanism which apparently could be fully understood simply in terms of the external events experienced by the animal. Pavlov worked on basic reflexes in animals and it might be argued that there are fundamental differences between these phenomena and those that a student of human psychology must study to account for all human behaviour. At this point Watson turned to Darwin and his theory of evolution. In his writings, Darwin had stressed the continuity of species including the then controversial idea that humans evolved from apes. Crucial to Darwin’s thinking was that the continuity between species was not only biological but also behavioural. Thus, in a memorable quote Darwin asserted that: ‘Psychology will be based on a new foundation, that of the … acquirement of each mental power and capacity by gradation. Light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history.’

| This illustration shows the stages in human evolution that have occurred over the last 35 million years. As the physical form changed, the mind also developed |

Watson used Darwin’s evolutionary theory to argue that psychology could be studied meaningfully by systematic investigation of how simpler animals learned, that all animals, including humans, learned in the same way and that humans were quantitatively, not qualitatively, different from other animals. In his writings, Watson not only sought to dismiss mental concepts from the realm of scientific psychology, he also argued that they could never play any causative role in the explanation of behaviour; they were epiphenomena. An epiphenomenon is something that happens as the end result of a process—rather like the exhaust fumes of an engine. Consciousness, for example, was attributed to feedback when the throat muscles initiated speech responses. As for images, Watson denied that they existed at all and challenged anyone to prove him wrong (Bolles, 1979).

Watson’s account of learning was, in essence, extremely simple. All behaviour arose as a result of conditioned relationships between stimuli and responses. In order to understand why an individual behaved in a certain way, one need look no further than the observable events surrounding the development of that individual. To make this point forcibly, Watson carried out the now famous experiment on ‘Little Albert’ in which a previously neutral stimulus, a white rat, was paired with a noxious stimulus, a loud bang, until a point was reached where Little Albert cried at the appearance of the rat on its own. Later, Watson suggested that Albert might seek psychoanalytic help to understand his fear of rats when all that was needed was knowledge about how he had been conditioned.

Early doubts about behaviourism

From the outset, not everyone shared Watson’s view that behaviour could be explained fully without the help of unobservable constructs. This was true even for those who worked on learning in animals. Edward C. Tolman was strongly opposed to the idea that all behaviour could be understood solely in terms of the relationship between stimulus and response and, along with his students, he designed ingenious experiments which challenged the extreme behaviourist view. Tolman argued that most behaviour was determined by a general goal rather than a set of inflexible links between stimuli and responses. For example, a bird has the goal of building a nest but the resultant behaviour is flexible, taking account of variations in the availability of nest building material and other events that might intervene during the process.

FIGURE 1.1 | Watson and Tolman: both behaviourists, but with very different ideas about the role of mental representations in the explanation of behaviour |

Linked to this idea of a goal, Tolman argued that when animals were learning they developed an internal representation of the problem they were trying to deal with—something he termed a cognitive map. In one experiment, rats were taught to swim through a maze to obtain food from a goal box. The water was then drained from the maze and the rats placed in the maze again. Almost immediately they were able to run through the maze to obtain more food (MacFarlane, 1930). According to strict behaviourist ideas this transfer of learning should have been a very slow process because of the massive change in responses required (swimming to walking) and stimuli (wet to dry). Tolman argued instead that the rats had developed some internal representation of the maze so that they ‘knew’ where the food was independently of the specific physical conditions under which they had learnt about the maze.

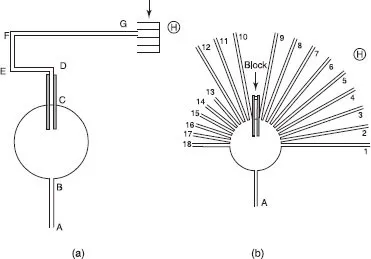

Perhaps Tolman’s most famous experiment is one in which rats were first trained to run through a runway to obtain food from a goal box (Tolman et al., 1946, and Figure 1.2a). Once this response was established, the apparatus was changed by the addition of 18 new pathways and the blocking of the pathway the rats had learned to run down (see Figure 1.2b). The interesting question was, where would the rats go now? According to a simple stimulus–response account, the rats would either have no idea where to go or, if some degree of generalisation had occurred, they might preferentially choose paths 9 or 10 because these are most similar in position to the trained pathway. In fact, the rats greatly preferred pathway 5—a finding Tolman attributed to the rats having a map of where the food was.

FIGURE 1.2 | (a) Initial training arrangements used by Tolman. The animal learns to run the route indicated by letters A–G to obtain food. H represents a permanently lit light bulb. (b) Learned path is blocked at point D. Stimulus generalisation would predict that pathways 9 and 10 would be most preferred but it was 5 and 6. This indicated to Tolman that the animals must have a map of the training area enabling the most direct route to be taken |

Gestalt psychology

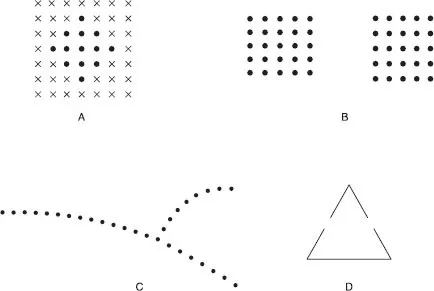

At the same time as Tolman was working on cognitive maps, a group of German psychologists left Nazi Germany and set up a new school of psychology in the USA. This group of psychologists, which included Koffka, Kohler and Wertheimer, became known as the Gestalt psychologists (Koffka, 1935). Gestalt means ‘shape’, ‘form’, or ‘figure’ and the basic tenet of these psychologists was that groups of stimuli can have emergent properties, or put another way, ‘the whole can be more than a sum of its parts’. Gestalt psychologists developed their arguments largely on the basis of two-dimensional figures that revealed organisational principles which were not inherent in the components of these figures. The most fundamental of the Gestalt ‘laws’ was the law of Pragnanz, or ‘good form’. This stated that if a number of different organisations (gestalts) of stimuli are possible, it is the most stable or ‘best’ that will be preferred. This concept is best understood by looking at Figure 1.3 which shows four ‘laws’, each of which can be considered as a variant of the law of good form.

While the Gestalt demonstrations are very powerful, the theory that went along with them was rather weak. The Gestalt psychologists argued that because more than one organisation of a configuration was possible, there must be some internal structure that mediates perception and determines that a particular configuration is preferred. This in itself was a straightforward conclusion, and one that was diametrically opposed to behaviourism, but their ideas as to what the internal representation was were never properly developed. Their principal idea was that of isomorphism, in which a particular gestalt was thought to set up a corresponding electrical force in the brain which served as the basis of perception. The Gestalt psychologists were also nativists, believing that the mechanisms of perceptual organisation were inherited. We now know that nativist assumptions are not always correct and that experience can determine how we see the world.

FIGURE 1.3 | Stimulus arrays illustrating four different Gestalt ‘laws’: (A) law of similarity (similar items grouped together), (B) law of proximity (items closer together form groups), (C) law of good continuation (line of dots follows smooth continuation rather than sudden change of direction), (D) law of closure (gaps are ‘filled’ to indicate a form) |

Skinner and language

Watson bowed out of academic life prematurely as a result of a domestic scandal, but by then the behaviourist movement had an enormous momentum with new figures adopting the same stimulus–response framework. These figures included Edwin Guthrie and Clark Hull but the most famous was B.F. Skinner. The major achievement of Skinner was to establish that conditioning took two forms. We have already considered classical conditioning in which a pre-existing, innate response comes to be associated with a new stimulus. Skinner pointed out that there was another form of learning which he termed operant conditioning. According to this idea, an animal may produce a response and, depending on the outcome, that response may or may not be repeated when the same situation is encountered again.

The most famous operant conditioning situation is a rat confronted with a bar. At some point the stimulus of the bar is sufficient to arouse the rat’s interest and the animal presses it with one of its paws. In this instance the bar press is met with food. This positive reinforcement ensures that this response will happen again. In contrast, delivery of a mild electric shock might serve as punishment and make bar pressing less likely. This basic learning situation can be developed by, for example, arranging it so the rat learns that a bar press means food only when a red light is on, or that the bar will deliver food only after a certain amount of time has elapsed.

Skinner shared Watson’s mechanistic view of human existence and likewise was not concerned with any notion of internal representations governing behaviour. For Skinner, the development ofan individual was entirely determined by the individual’s reinforcement history. Thus a...