eBook - ePub

Toward A Logic of Meanings

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Toward A Logic of Meanings

About this book

This book, the last one written by Piaget, presents a new line of empirical studies based on a revised formulation of his theory of the development of logical reasoning. The amended theory overcomes many problems and criticisms of his earlier formulations by providing a fresh explanation for the origin of mental operations and mental organization based on the concept of meaning. It also offers a more elegant vision of the continuity in mental development from birth to adulthood. As the final revision of Piaget's theory -- and one that opens up new areas of inquiry -- this book calls for a reinterpretation of his earlier work -- a task which will occupy scholars for decades to come.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Toward A Logic of Meanings by Jean Piaget,Rolando Garcia,Philip Davidson, Philip M. Davidson,Philip M. Davidson,Jack Easley, Philip M. Davidson, Philip M. Davidson, Jack Easley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Developmental Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

by

Jean Piaget

Translated by D. de Caprona and P. M. Davidson

Introduction

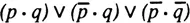

Our main purpose in this book is to complete and to amend our operatory logic in the direction of a logic of meanings. It is already such a logic in the extensional sense of the term, and it is therefore in the intensional sense that we shall have to specify the use of logical connectives such as “and” and “or,” and, above all, the use of “meaning implications” as opposed to “material implications.” The difference between the two types of implications is that the latter are defined with respect to the truth values of statements, irrespective of their meanings or the meaning of the relation between them. Thus, considering only extensions, it suffices that any one term of the disjunction

be true in order to derive the implication p ⊃ q—even if there is no meaningful relation between p and q. This is the source of several well known paradoxes.1

Therefore, it is essential to construct a logic of meanings whose major operation we shall call a “meaning implication”: p implies q (written p → q) if one meaning m of q is embedded in the meanings of p and if this meaning m is transitive.2 In this case, the embeddings of various meanings according to their relative comprehensiveness—which we shall call “inherences,” correspond to extensional nestings, and therefore to kinds of truth tables. However, such truth tables are partial and are determined by meanings, and negations are relativized according to these nestings taken as frames of reference.3

If such a logic of meanings really exists, there is no reason why it should be limited to propositions or statements, for any action or operation also has meanings. As no action, no operation, and above all no meaning is isolated but is bound up with many others, there are implications among the meanings of actions or of operations. Such implications are distinct although inseparable from the causal aspect, or the actual execution, of actions.

Our second purpose therefore is to advance the analysis of implications between actions or operations, by going back as far as possible to the level of practical action and in the direction of the most elementary inferences. At the level of true operations (around six to ten years), the analysis is straightforward. For instance, an operation that combines objects x into a class obviously implies an exclusion of objects y (or non-x). As Spinoza said, omnis determinatio est negatio. But with respect to practical actions, we must distinguish their causal aspect (the outcome that is verifiable after the fact) from their anticipation, which is inferential. An action in itself is neither true nor false, and is evaluated only in terms of effectiveness or usefulness in relation to a goal. Whereas, an action implication involving anticipations is either true or false and therefore already constitutes a logic, even at the most primitive levels. In addition, because meanings ensue from the assimilation of objects to the subject’s schemes, and reciprocally, all assimilations engender meanings, a causal succession of observable events is a sufficient condition for implications between meanings. For example, an object x might be laid on a support y which the subject could use to draw it back, or else it might be placed next to the support. Observing either situation brings out implications between meanings, as long as the subject understands that in the latter case it is useless to pull at the support: the relation or action “laying down upon” has acquired the meaning of a “reason.”

From this standpoint, various levels can be distinguished. The most elementary one consists in constructing action, object, and relation schemes in the midst of the global perceptual images that comprise the newborn infant’s world. In this initially undifferentiated universe, any change at first merely amounts to substituting one global picture for a previous one, without any detailed analysis of possible modifications. Starting with this essentially syncretic situation, the first cognitive endeavors are tantamount to carving out a number of relatively isolable and stable elements through repeatable actions (the origin of action schemes). Thus, objects and relations are formed, serving as content for inferences or implications between meanings and actions.

We have previously described the arduous and rather late (age 10-12 months) conquest of object permanence under various conditions in which the object is screened.4 Since then, many works (by Bower5 and others) have shown that this construction is even more complex than in our description. Recent studies6 describe other schemes that are elaborated around 9-10 months. Faced with empty cubes of various sizes, with sticks and small balls of plasticine, some subjects show an intention to insert a smaller cube in a bigger one but, interestingly enough, instead of directly doing so, they first put it in their mouth: They construct the container-content scheme (in the present case, a relation), through a form of “reflective abstraction,” from the routine and well established scheme of “putting something into one’s mouth.” They then extend it to new, somewhat intercoordinated schemes or sub-schemes such as to insert and to take out, to fill and to empty, or to iterate the inserting action so that a cube which is a “content” becomes a “container” for a smaller cube. The balls, cubes and sticks will eventually all be used as contents and the six cubes as containers.

As for the balls of plasticine, babies will stick two or more together in order to constitute a continuous whole, then separate them to restore the previous discontinuous state. Other objects, sticks for instance, will be used for hitting, throwing, pushing, and so on. These facts are interesting in that they show the construction of relational schemes which may be intercoordinated, especially when a positive action (such as inserting, etc.) is followed by the reverse action (taking out, emptying, etc.). This comprises the beginning of implications among actions, such as “action x implies the possibility of the reverse action.” Various processes such as differentiation of actions, individualization and localization of objects, clustering, elementary classifying activities, correspondences, and so on, can also be observed.

We may call this initial level a “protological” one, understanding by this a preparatory phase leading to the instruments for deduction proper. This phase is marked by the formation and coordination of the first assimilation schemes, and therefore of the first meaning implications (for instance, when relations are established between vision and grasping through a progressive evaluation of accurate distances).

This initial phase is followed by another level, still characterized by sensorimotor implications among actions, which in this case are sufficiently systematic to engender stable structures. For instance, once object permanence is elaborated with respect to objects temporarily hidden by a screen, the subject will discover that they occupy the last of their successive positions and not the first one. This implies that positions and displacements are co-ordinated, and therefore that the “group of displacements”7 is being formed. Needless to say, such structurations require not only the constitution of positive implications, but also an adequate use of exclusions or negations, in addition to the above-mentioned initial inversions.

When the semiotic function is being elaborated, action implications are accompanied by verbal expressions, leading to meaning implications among statements. Such implications are still determined by meanings and cannot be reduced to extensions, as they remain dependent upon nestings and inherences lacking a general truth table.

At this level, our studies yield a third interesting outcome: We observe the formation of rudimentary operations in action contexts, each of which is isomorphic to one of the sixteen binary operations of prepositional logic. Naturally, these precursory operations are isolated and related to specific meanings, rather than being organized into structured wholes (such as groupings, etc.). We formerly considered such operations as characteristic of systems that are elaborated around age 11-12, and had two reasons for thinking so. First, this period marks the beginning of hypothetico-deductive thought, the capacity to infer necessary consequences from sheer hypotheses, without depending on data (as at the level of “concrete operations,” around 7-10 years). The second reason for supposing a late development is that at the hypothetico-deductive level, these 16 operations arise as a system of relations between inverses (N) and reciprocities (R) constituting quaternary groups (the INRC groups in which C is the inverse of R and the correlative of identity I).8 These groups are used for example in solving problems of physics, such as those involving the equality of actions and reactions. Therefore, it is both striking and instructive to rediscover the 16 operations at the level of the coordinations among actions, well before deductive thinking and a fortiori well before INRC structures are used.

What we actually observe at early levels are the 16 possible ways of combining pairs of actions, without systematic interrelations, in which each combination is performed according to context. Moreover, as the logical connectives “and” or “or” have various intensio...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Editors’ Comments

- Part One

- Part Two

- Author Index

- Subject Index