eBook - ePub

Psychoanalysis And The Humanities

- 168 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Psychoanalysis And The Humanities

About this book

First published in 1996. Written by distinguished artists and scholars with psychoanalytic training, this seminal collection of essays spans the humanities-painting, sculpture, literature, history, anthropology, and philosophy-illustrating how psychoanalytic thinking can powerfully enhance these disciplines. The essayists address a question first posed by Freud in his 1919 article, Should Psychoanalysis Be Taught at the University? With a resounding Yes, they underline the intellectual enrichment to be gained from the application of the psychoanalytic method to humanistic disciplines and, conversely, the need for contemporary psychoanalysts to acquire the kind of historical and classical education taken for granted by their counterparts earlier in this century.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Duchamp, Freud, and Psychoanalysis

Seymour Howard, Ph.D.*

After recapitulating academic, impressionist, symbolist, expressionist, cubist, and futurist art styles, Marcel Duchamp “saw the light” in 1912, essentially forsook the brush of “stupid” painters, and began to make outré works of novel mechanomorphic imagery. Aristocratic, ectomorphic, esoteric, diffident, reclusive, pseudocelibate, apolitical—Marcel Duchamp, as a counterculture antihero, represents the polarized complement to the century's last great orthodox old master, Picasso. In hermetic yet populist ways, Duchamp synthesized media and genres ranging from music, glass, marzipan, and lead to game playing, optics, and the chances of Eros in life itself as well as in programmed performances—an approach to art explored by avant-garde allies and successors to the present. His “revolutionary” found-object “readymades,” chosen products of mass manufacture and anonymous collective intelligence, so enigmatic to the unreflective eye, remain pregnant with affect for novices and initiates alike, owing to their selection, orientation, and identification. Like Rorschach blots and Thematic Apperception Test pictures, as well as other images, words, and things, they elicit deeply personal and socially shared perceptions, a process that reflects the creative and primary process.

This study deals with selected works by Duchamp, considering meanings in and between them, their ambience, and their maker. Created in his adopted new “ism,” an added dimension of eroticism, with its playful use of the polymorphic components revealed by Freud, they are of fundamental interest and import for the history of psychoanalysis and its connections with so-called high and low culture. Freudian, psychoanalytic associations to and explanations of the life and works of Duchamp are abundant; his deeply informed and witty probings into chance and preconscious inspiration parallel the use of psychoanalytic studies in contemporary cultural development. Duchamp himself was a pioneer in exploring the psyche, in private and idiosyncratic ways.

At the end of his life, Duchamp summarized the role of eros in his work:

Cabanne: What is the place of eroticism in your work?Duchamp: Enormous. Visible or conspicuous, or, at any rate, underlying. … I think this is important because it's the basis of everything, and no one talks about it. Eroticism was a theme, even an “ism,” which was the basis of everything I was doing at the time of the Large Glass. It kept me from being obligated to return to already existing theories, aesthetic or otherwise. (Cabanne, 1971, p. 88)

The chronological sampling that follows introduces some of the many possible associations implied in the works—with the virtues and vices of explanation, which resides ultimately in the thing itself.

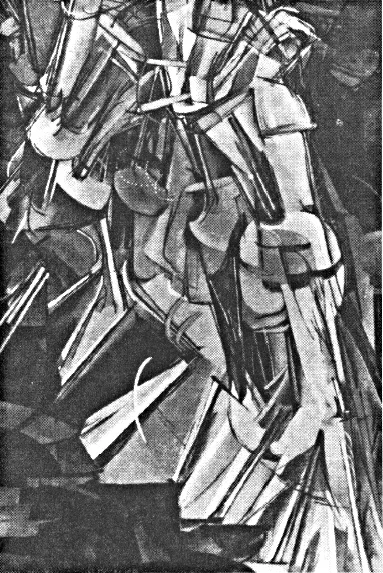

Nude Descending a Staircase (1912)

After leaving his native Rouen and joining his two older artist brothers, Jacques Villon and Raymond Duchamp-Villon, in Paris in 1904, Marcel Duchamp worked as an illustrator of sometimes risqué cartoons. His salon-style paintings then included lyric semienigmatic nudes reflecting symbolist, impressionist, and Fauve traditions (Schwarz, 1969, nos. 79–110; nos. 89–162 passim). Nude Descending a Staircase, (Figure 1; Schwarz, 1969, no. 181;

Figure 1 Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase (Nu descendant un éscalier), No. 2, Neuilly, January 1912, oil on canvas, inscription “NU DESCENDANT UN ESCALIER,” 146 × 89 cm. Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

Bonk, 1989, no. 10) a more advanced work, in a cubist and quasi-futurist idiom of dissecting abstraction, also reveals his study of recent “scientific” x-ray and multiexposure cinematic and stroboscopic photographs—idiosyncratically recombined in images later smeared in (like feces) with his fingers (Lebel, 1959, p. 15).

The cubist painter and theorist Albert Gleizes and his colleagues, rejecting its unorthodoxy, enlisted Duchamp's brothers to ask Marcel to withdraw the painting from the 1912 Salon d'Automne (Cabanne, 1971, pp. 31f.). Dismayed by their narrow chauvinism, Duchamp acquiesced and left for revolutionary Blau Reiter Munich, where he probably encountered Kandinsky's booklet On the Spiritual in Art, also translated by him for his brothers (Tuchman, in Tuchman et al., 1986, p. 47); an enlightened industrial arts exposition (De Duve, in Kuenzli & Naumann, 1989, pp. 41ff.); and perhaps local controversy about Freudian methodology (Jones, 1953–1957, vol. II, p. 118). He continued on to Freud's Vienna, Kafka's Prague, and postsecessionist Berlin. In Munich, Duchamp developed a more transparent and dissecting idiom, reminiscent of anatomical studies by Leonardo and Vesalius that combine many views and contours of skin, bone, organ, and connective-tissue fragments executed in segmented traces of motion and expressing erotic metamorphic and mechanomorphic fantasies.

Earlier stages in the design of Nude Descending a Staircase are noteworthy for their erotic “Freudian” constants and transformations—autoerotic, incestuous, coital, and hallucinatory. His works confessedly “commemorate psychological events of his life” (Lebel, 1959, p. 13). Duchamp's 1911 pencil sketch of a young man ascending stairs, illustrating a favorite poem by Jules Laforgue, evolved into a stroboscopic self-portrait oil sketch, Sad Young Man in a Train (1911; Schwarz, 1969, nos. 175, 179; cf. no. 87). It recorded a visit to his younger sister, Suzanne, with whom he was paired by age and affection. The subsequent suggestively syncopated and gyrating Nude Descending a Staircase and its oil sketch in turn prefigured erotic and coital actors in his King and Queen Traversed by Nudes at High Speed and companion works (Schwarz, 1969, nos. 180, 186–194). The subject and dreamlike imagery recall, too, a popular array of descending transcendental beauties by the pre-Raphaelite Edward Burne-Jones (The Golden Stair, 1880), a school much admired by Duchamp; Lewis Carroll's antics and self-transformations in Alice in Wonderland, a source that Duchamp frequently revisited; and contemporary dreamlike slow-motion films, later used by his friend Fernand Leger for the same subject in a way that exposes its erotic implications.

The use of a prominently lettered title was similarly prophetic and regressive. Such a revolutionary and archaic mix of media—mute illustration and descriptive narrative—appears in Egyptian murals, Greek vase paintings, and Medieval illuminations, as well as in modern popular advertising and comics. Like Freud, Duchamp was working with often ignored or repressed primary historic as well as contemporary materials in personal and professional ways that were also being addressed by experiments in the arts and sciences informing both men.

The Large Glass (1915–1923)

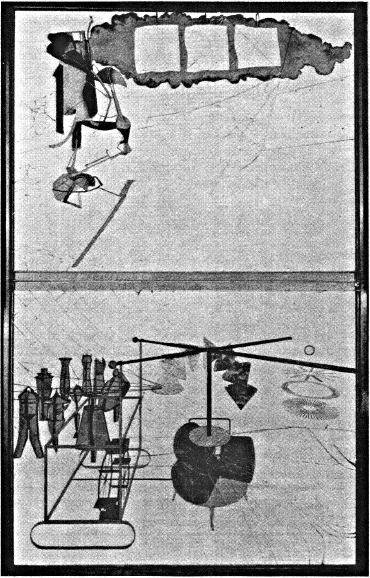

The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (Figure 2; Schwarz, 1969, no. 279; Bonk, 1989, no. 2), the major production of a decade and the fruit of the foregoing development, followed several affective and artistic crises: Duchamp's distressed and leavening sojourn in Germany; a motor trip in France with the artistic revolutionaries Guillaume Apollinaire, Francis Picabia, and Picabia's wife, Gabrielle Buffet (after they had seen Raymond Roussel's revolutionary surrealist and for Duchamp transformative play Impressions of Africa), when the young painter literally saw the light and turned to the life of an avant-garde philosopher-artist; a vacation in England with his newly divorced sister, Suzanne; and, most important, his first stay in New York City, during much of World War I, after his medical deferment from military service and the great success of Nude Descending a Staircase at the Armory show there (1913). The final work, two sheets of plate glass “painted” in many novel ways, was preceded and accompanied from 1913 on by innumerable sketches, ancillary studies, and notes describing his thoughts and methods, eventually reproduced in The Green Box (1934; Schwarz, 1969, nos. 190, 198–204, 211–218, 220f., 230f., 253, 269f., 279).

The imagery and annotation of The Large Glass reveal a massive bibliophilic intellect and invention informed by the study of ancient and modern masters of mathematics, philosophy, paleography, physical sciences, mechanical drawing, literature, other sister arts, and various popular and esoteric traditions. Its idiosyncratic mechanomorphic forms, drawn from a private and markedly

Figure 2 Marcel Duchamp, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (La mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même): The Large Glass, New York, 1915–1923, oil paint, varnish, lead foil, lead wire, and lacquered dust on two plate-glass windows (now cracked) framed in steel, 278.5 × 175.8 cm. Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

outré self-referential universe of mind-boggling complexity, resemble, and possibly simulate, the frenzied and withdrawn fantasies and fugues of psychotics. Psychoanalytically it has been said to illustrate narcissistic onanism, misogyny, castration fear, anal retention, sadistic fetishism, aggression, self-destruction, exhibitionism, procrastination, oedipal ambivalence, magical thinking, schizophrenia, autism, and so on (e.g., Lebel, 1959, esp. pp. 71–73; Paz, 1968, p. 22; and, passim, Schwarz, Marquis, Jagoda, and Jouvenot).

Duchamp, however, was far from mentally ill; his social aplomb and objectivity, as well as uncensored self-awareness, were legendary. For example, he openly acknowledged to the admiring Lebel an unforgettable guilt-ridden nightmare in Munich in which he became a metamorphosed Kafkaesque insect, presumably recalled in his wittily self-aware and self-incriminating “texticle” pun, “An incesticide must sleep with his mother before he kills her. Bed bugs are indispensable” (Lebel, 1959, p. 73 n.).

In The Large Glass, Duchamp produced an incohate art cru or art brut of unprecedented sophistication—figuratively, a step into space from square one.

Succinctly characterized by him as an Assumption and a modern conception of women (Duchamp, 1973, p. 39; Janis & Janis, 1945), the work, with pseudotransparent mass-manufactured clarity, transforms the religious dramas of Gothic stained glass and the Renaissance perspectival “window onto nature” into a contemporary yet timeless mystery-romance, with referents r...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Contributors

- Introduction

- Sigmund Freud's Philosophical Ego Ideals

- Cézanne: The Large Bathers II

- Duchamp, Freud, and Psychoanalysis

- Alberto Giacometti's No More Play: A Monument to Ancient Magic, Fertility Goddesses, and Universal Ambivalence Toward Women

- Writing the Unconscious

- Anthropology and Psychoanalysis: Bridging Science and the Humanities

- Psychoanalysis and History

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Psychoanalysis And The Humanities by Laurie Adams, Jacques Szaluta, Laurie Adams,Jacques Szaluta in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Mental Health in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.