![]()

1 Human comfort and ventilation

1.1 Introduction

The purpose of a ventilation system is to provide acceptable microclimate in the space being ventilated. In this context, microclimate refers to thermal environment as well as air quality. These two factors must be considered in the design of a ventilation system for a room or a building, as they are fundamental to the comfort and well-being of the human occupants or the performance of industrial processes within these spaces. In a modern technological society, people spend more than 90% of their time in an artificial environment (a dwelling, a workplace or a transport vehicle). As a result of the energy-saving measures which started in the early 1970s these artificially created ‘internal’ or ‘indoor’ environments have undergone radical changes, some being positive and others negative. On the positive side, increased levels of thermal comfort have become fait accompli through improved thermal insulation and more advanced air-conditioning or heating system design. On the negative side, a deterioration of the indoor air quality has been experienced particularly among air-conditioned buildings [1]. Indeed, the term ‘sick building syndrome’ is synonymous with the energy-saving era. These indoor air quality problems have been associated with poor plant maintenance, high concentrations of internally generated pollutants and low outdoor air supply rates.

The designers and operators of ventilation systems should be familiar with the comfort requirements and the quality of air necessary to achieve acceptable indoor climate. These require knowledge of the heat balance between the human body and the internal environment, the factors that influence thermal comfort and discomfort as well as the indoor pollution concentrations that can be tolerated by the occupants. In recent years, there has been a flux of published information, notably from Scandinavia and the USA, on these important issues of the built environment. The fundamental work that has been done on thermal comfort and air quality will be discussed in the first part of this chapter and more recent developments will be presented in the second part. This chapter will then become the fulcrum for the remaining chapters of this book.

1.2 Heat balance equations

1.2.1 Body thermoregulation

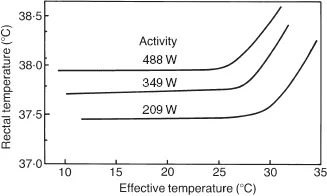

The primary function of thermoregulation is to maintain the body core, which contains the vital organs, within the rather narrow range of temperature which is vital for their proper functioning. The temperature control centre is the hypothalamus, a part of the brain that is linked to thermoreceptors in the brain, the skin and other parts of the body such as the muscles. The hypothalamus receives nerve pulses from the temperature sensors and coordinates information to different body organs to maintain a constant body core temperature. The thermoreceptors are particularly sensitive to changes in temperature and temperature change rates as small as +0.001 and –0.004 Ks–1 can be detected. Temperature regulation is carried out by controlling metabolic heat production rate, control of blood flow, sweating, muscle contraction and shivering in extreme cold situations. Under normal conditions the body core temperature, tc, is approximately 37 °C and this is maintained at a constant value despite changes in the ambient temperature, as shown in Figure 1.1 for three levels of activity [2]. The figure shows the ability of the temperature-regulating mechanisms to maintain a constant core temperature up to a certain ambient temperature beyond which core temperature cannot be maintained because evaporative cooling of sweat becomes ineffective. It is also shown in Figure 1.1 that the core temperature is not always constant but depends on activity, i.e. increases with increase in metabolism, and may be as high as 39.5 °C in extreme activities.

Figure 1.1 Rectal temperature as a function of ambient temperature for three activities.

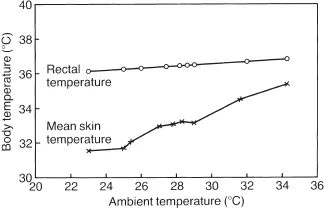

While the body core temperature remains almost constant over a wide range of ambient temperatures, the skin temperature changes in response to changes in the environment and is usually different for different parts of the body. However, the variation in skin temperature over the body is reduced when the body is in a state of thermal equilibrium and comfort. The variation of mean skin temperature, ts, for a nude person with ambient temperature is shown in Figure 1.2, which also shows the rectal temperature for the purpose of comparison [3].

1.2.2 Heat transfer between body and environment

The heat balance equation for the human body is obtained by equating the rate of heat production in the body by metabolism and performance of external work to the heat loss from the body to the environment by the processes of evaporation, respiration, radiation, convection and conduction from the surface of clothing. Thus:

Figure 1.2 Variation of mean skin and rectal temperatures for a nude body with ambient temperature.

where

S = heat storage in body (

Δ

tb/θ where

θ is time), W;

M = metabolic rate, W;

W = mechanical work, W;

R = heat exchange by radiation, W;

C = heat exchange by convection, W;

K = heat exchange by conduction, W;

E = evaporative heat loss, W and

RES = heat loss by respiration, W. A positive value of

S indicates a rising body temperature,

tb, a negative value suggests a falling

tb, and when

S = 0 the body is in thermal equilibrium. The expressions that are used to calculate the terms on the right-hand side are given below, but for a more detailed assessment of each term readers should consult the books by Fanger [

4] and McIntyre [

5].

Metabolism (M) This is the body heat production rate resulting from the oxidation of food. Its value for every person depends upon their diet and level of activity and may be estimated using the equation below:

where

= air breathing rate, ls

–1; and

Foi and

Foe are the fraction of oxygen in the inhaled and exhaled air, respectively. The value of

Foi is normally 0.209 but

Foe varies with the composition of food used in the metabolism; for fat diet

Foe ≈ 0.159 and for carbohydrates

Foe ≈ 0.163.

The rate of metabolism per square metre of body surface area can be obtained using equation (1.2) and Du Bois’ area given as:

where m = body mass, kg and H = body height, m. For an average man of mass 70 kg and height 1.73 m, AD = 1.83 m2. Metabolism is often given the unit ‘met’ which corresponds to the metabo...