eBook - ePub

Thinking Men

Masculinity and its Self-Representation in the Classical Tradition

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Thinking Men

Masculinity and its Self-Representation in the Classical Tradition

About this book

Thinking Men explores artistic and intellectual expression in the classical world as the self representation of man. It starts from the premise that the history of classical antiquity as the ancients tell it is a history of men. However, the focus of this volume is the creation, re-creation and iteration of that male self as presented in language, poetry, drama, philosophical and scientific thought and art: man constructing himself as subject in classical antiquity and beyond. This beautifully illustrated volume, which contains a preface by Nathalie Kampen, provides a thought-provoking and stimulating insight into the representations of men in Classical culture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Thinking Men by Lin Foxhall,John Salmon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

This book explores artistic and intellectual expression as the selfrepresentation of man. Like its companion volume, When Men were Men: Masculinity, Power and Identity in Classical Antiquity (Foxhall and Salmon 1998), it starts from the premise that the history of classical antiquity as the ancients tell it to us is a history of men. However, the focus here is specifically on the creation, re-creation and iteration of that male self as presented in language, poetry, drama, philosophical and ‘scientific’ thought and art: man constructing himself as subject in classical antiquity and beyond, in more recent appropriations of that tradition.

Our view of classical antiquity is incomplete in several senses (cf. Fox, Chapter 2 in this volume), not least because we can only perceive it through the texts, images and objects which its men have left us (Foxhall 1995a). Indeed, creating the (male) self as the subject is most evident in the ancient languages themselves, implicit in grammatical gender, and in the interactions of language with the structuration of thought and politics (Stafford and Foxhall, Chapters 4 and 5 in this volume). ‘Female’ trees, like gramatically feminine virtues, are objects of men’s desire, domination and self-control.

This is not to say that there is only one kind of male self. Rather, I would argue that all male subjects strive to be central: they take themselves for granted, permitting no genuinely acceptable alternatives to that particular self, even if they must contend with alternative versions of ‘the’ acceptable self. Though there may have been different kinds of ‘real men’, and certain kinds of masculinity were indeed problematic in particular contexts (Osborne and Walters, Chapters 3 and 11 in this volume), it is intrinsic to any man constructing himself as subject to claim to be the only true subject. So, for example, for all that there may have been a deliberately ‘democratic’ image of ‘real/Real men’ expressed in the funerary art of classical Athens, it remains exclusively the citizen man who is constituted as subject through the positive celebration of men’s bodies (Osborne, Chapter 3).

Most alternatives are forced into subservience; some, notably women’s bodies, are not even considered as true subjects; while the body of the effeminate male (Walters and Fox, Chapters 11 and 2 in this volume) or the slave male (Montserrat, in Foxhall and Salmon 1998) constitues an anti-subject (see below). Other alternative masculinities display characteristics which are positively male, but negatively construed when they typify an ‘other’. The tough old men of the Acharnians (Foxhall, Chapter 5 in this volume) or the regularity with which masculine personifications focus on unpleasant qualities or ideas such as fear and envy (Stafford, Chapter 4) again highlight how a Greek male self endeavours to be the one, eliminating the competition it perceives for centrality.

The notion of hierarchy is implicit in the masculine construction of self. In phenomenological terms, hierarchies of gender are hierarchies of encompassment: inferior elements are swallowed up and ‘naturalised’ into subservience, most fundamentally via language, but also through picture, object and text. Irigaray (1993: 29–36) finds this in her comparative analysis of men’s and women’s use of language and discourse:

Most of the time, in men’s discourse, the world is designated as inanimate abstractions integral to the subject’s world. Reality appears as an always already cultural reality, linked to the individual and collective history of the masculine subject … the realities of which his discourse speaks are artificial, mediated to such an extent by one subject and one culture that it’s not really possible to share them. Yet that’s what language is for.

(Irigaray 1993: 35)

It is through such psycho-social and political processes, aided and abetted by deep-rooted cultural traditions and the structure of the languages themselves, that the creation of hierarchically inferior ‘others’ becomes ‘natural’. Part of that process of naturalisation is what we can see at several thousand years’ distance in the poetry, drama, art, etc. Hawley (Chapter 7 in this volume) uses the notion of the gaze, borrowed from film criticism, but almost immediately confronts the question of who is looking at whom. Unlike modern films, Greek tragedies and comedies were written by men for a male audience (irrespective of whether women were in the audience or not), with all parts of both sexes played by male actors. Unlike many modern films where the problematic is the gaze of men aimed at women as objects, the ‘gaze’ in this context appears to become reflexive, a reiteration of subject/man (Hawley; cf. Sommerstein, Heap and Pierce, Chapters 8, 9 and in this volume).

Similarly, in the Anakreontic songs of the symposion, and more widely in archaic lyric, the all-male context of performance shapes the way in which we must understand the shared knowledge of poet and audience. Though the poet may not appear to be engaged in the crude politics of sexual mastery, this shared knowledge, which includes the audience but simultaneously excludes and overwhelms the object of sexual desire, transforms apparent subservience to the beloved into power over him or her (Williamson, Chapter 6 in this volume). Here too the formulation of the object serves to underpin the superiority, indeed the existence, of the subject as subject.

The process of encompassment intrinsic to the creation of man/subject/self may also be related to the male fantasies about reproduction. In classical antiquity, despite long-standing philosophical, medical and ‘scientific’ debates about the nature of generation, reproduction (or at least the important part) was perceived as masculine, despite the fact that in humans motherhood is manifest but paternity is only inferred (Harlow and Rosslyn, Chapters 12 and 14 in this volume). It is significant, then, that when dealing with engendered non-humans and divine beings, fruitfulness and reproductive capacity in a physical sense have remarkably little to do with the construction of any kind of maleness (Foxhall, Harlow and Clark, Chapters 5, 12 and 13). Even in human societies and political systems paternity takes on meanings inflated beyond the perceived physical significance of the time. The suspicion arises that for the assembling of the male self as subject, ‘reproduction’ in other senses (political, intellectual, spiritual) than the physical is more important, since the latter can be relegated to women, though perhaps not unproblematically.

The strength of this trajectory of constituting masculine subjectivity further disallows the possibility that any other kind of self can be a subject (rather than object). This removes the possibility of self-hood from ‘others’, especially women. Virtuous women in the late antique, Christian Roman Empire usually became ‘virtuous’ by giving up their womanhood and becoming ‘manly’ (Harlow and Clark, Chapters 12 and 13 in this volume). Hence the one woman who maintains her womanhood and her virtue intact, constituting a whole, if inferior, identity, is Mary, who dwells in the realm of the miraculous (Harlow, Chapter 12). On the other hand, the apparent acceptability of portraying violence against inferior others reduced to object status, e.g. the rape of women as integral to the plots of New Comedy (Sommerstein and Pierce, Chapters 8 and in this volume), may also be an outcome of the construction of the man/self/subject as expressed in drama.

The removal of the possibility of self-hood happens in degrees with ‘other’ kinds of men and male being, but never so absolutely as for women. Partly this is a problem of boundary crossing: effeminate men and manly women are anomalies, and thus threaten the established perceived order. Indeed, the ‘other’ man (who is never a real alternative) appears to pose particular threats to the constitution of the ‘true’ and ‘right’ masculine subject (just in case he might be mistaken for a real alternative by being ‘he’), so that he is represented in a particularly hostile way (Foxhall and Walters, Chapters 5 and 11 in this volume).

‘Texts’, whether written, iconographic, concrete or spatial, express only a fragment of any male self. As Fox (Chapter 2 in this volume) points out, we are constrained by the inability to attain/reconstitute the Real. Though ‘texts’ (sensu lato) are created by a Real subject we can only extract an incomplete one: in this regard ‘historical’ texts are no more or less Real than the literary and imaginary. And we cannot fully account for the realms or directions of fantasy and desire expressed in literary or artistic representation (Heap and Fox, Chapters 9 and 2 in this volume). In trying to come to terms with the interaction of reality and representation, representation is perhaps best cast as a fragment of the reality of the mind.

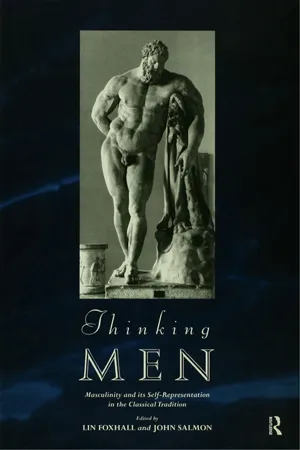

An example might be found in the creation of heroes, for which classical antiquity is celebrated, and who can only be Real(?) men, never women or the wrong sort of male. However, the relationship of heroes to real/Real men is hard to fathom. There are many different kinds of hero, though Homeric epic provided the most important prototypes (cf. van Wees 1998). In contrast, there is the enormous popularity of Herakles in words and images – at one level an everyman (Fox, Chapter 2 in this volume), but also the superhero who embodies – what? Certainly not the ‘right’ kinds of masculine quality which constituted the ideal man/subject of classical Athens or Republican or Imperial Rome (Osborne and Hawley, Chapters 3 and 7 in this volume). Though he exhibits strength, power and ultimately mastery, he himself is dominated by another. Although he gains control, he never attains self-control, the self-domination forming the core of the male subject/self. In iconography and in myth his reputation for gluttony and other forms of excess is regularly depicted, hence, perhaps the reason he was portrayed as both a comic buffoon and a tragic hero: the voluptuous Farnese Herakles on the cover of this volume epitomises both of his images. Was Herakles, then, more a product of subject/man’s fantasy than his idealism? Did every little boy really want to grow up to be Herakles, rather than Achilles or even Perikles? (And, presumably none wanted to be, or admitted to wanting to be, Oidipous?)

What is also extraordinary (or maybe not – perhaps this is a tribute to its seductiveness and its force?) is the way in which the processes and terms of creating subjects and object-hood remained unchanged through the great spiritual and intellectual revolutions of late antiquity: the ascendance of Christianity. A priori, Christianity would seem to stand as a challenge to the old subject-object relations, and to invite the possibility of redefining subjects and objects in radically new terms of wholeness and equality. This is, in fact, never Realised. Though women might attempt to turn into men in the process of yearning for subject identity, they never achieve it (Harlow and Clark, Chapters 12 and 13 in this volume). Christianity might seem to provide the perfect opportunity for actualising the potential of the gender-neutral human subject on offer in the Greek language (anthropos) (Clark, cf. Stafford, Chapters 13 and 4), but here is another chance missed: anthropos turns out to mean ‘he’, not ‘she’. Perhaps this is also why, even in modern times, writers have deliberately drawn upon classical models to replicate relationships depicting man as self-constituted subject attempting to encompass woman as object, in the process expressing their fears about what might happen if this were not so (Rosslyn, Chapter 14).

That the creation of man/subject disallows the creation of woman/subject, denying her an identity, and in its constitution and embodiment denies other kinds of male, especially less-male, identities, ultimately falsifies the subject status since it depends for its own integrity on the negation of the integrity of others. If woman as woman is obliterated, who is man as man? By explicitly forefronting the masculine subject/the male self in our exploration of these ‘texts’ we sing the songs of ancient times with a new voice. Who knows, perhaps some day we shall break the cycle of the Labdakids?

2

The constrained man

This chapter is concerned with the methodology of the study of masculinity; in particular masculinity in classical Athens. As an area of study, in one sense this is relatively new, and there is some reason to find in novelty the promise of better methodology. Gender-related work necessitates greater awareness of the critics’ position in respect of their material; the subject is politically motivated, and one cannot for long avoid the abyss separating what we want to get out of gender studies and what the evidence will reveal. But in spite of self-awareness, interest in masculinity as a historical topic has clearly arisen from other concerns in our own lives, and we must be wary of thinking that a new disciplinary direction will guarantee critical integrity. One might imagine that by lucky chance, men’s studies arose in a climate where a more self-critical vision of historical work was already becoming a consensus, taking Foucault as the emblem of this good fortune. But this tempting vision of our own credentials is illusory, and cannot safeguard us from the discomfort of potentially destructive enquiries into the assumptions with which we look at ancient man. There was no clean break which heralded the arrival of man as an historical topic; and stated like that, it is embarrassing to think that anything remotely novel or even interesting is involved.

I shall explore here the notion that man at Athens was at the centre of a constrictive ideological network, an idea which threatens to become something of an orthodoxy. By looking at why we think of Athenian man as constrained, I am not aiming to make definitive claims for a new view of Athenian man. Rather, I hope to make clear what a vision of constraint entails; essentially a certain view of the relationship of discourse to ideology which I believe, from a psychoanalytic and linguistic viewpoint, to be untenable. I want to bring into the debate an area which historians do not customarily confront. That area can be called critical need; the desires which motivate students of Athens, which influence the boundaries of what we study and the kinds of analysis we produce. In picturing the Athenian citizen male as operating within a network of constraints, these critical needs are particularly prevalent.

The most monolithic statement of the idea that the Athenian citizen was the subject of a network of social forces which acted to curtail his personal freedom is Winkler’s The Constraints of Desire, especially Chapter 2, ‘Laying down the Law: The Oversight of Men’s Sexual Behaviour in Classical Athens’ (Winkler 1990a: 45–70). Winkler isolates a sense of competitiveness as the dominating principle of public and private life.1 The citizen is bound by the conventions of his society both to exercise mastery over his social inferiors, and to devote the same effort to mastering himself. The threat which hung over him if he did not was symbolised in ‘the life of the kinaidos’; a phrase translated from Plato’s Gorgias (Winkler 1990a: 55ff.; Plato, Gorgias 494e; see also Foucault 1985: 190f.). Winkler treats this polarity as a manifestation of the zero-sum formula by which he characterises the competitiveness of Athenian life: in Athenian sexual morality (and thus personal morality on a larger scale) there was no such thing as a middle position: if you were not manly, you were a kinaidos. At least, an absence of positive manly attributes would lay you open to vilification as unmanly. The same mechanism is applied to what might be called socio-sexual positioning, pursuing a model which looks at sexual relations within the context of social ones: either you penetrate or are penetrated, and this dichotomy motivates the individual’s competitive spirit. The citizen elite consists of individuals dedicated to maintaining their reputation; to penetrating others, retaining identification with an integrated a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Plates

- Notes on Contributors

- Preface

- List of Abbreviations

- 1. Introduction

- 2. The constrained man

- 3. Sculpted men of Athens: masculinity and power in the field of vision

- 4. Masculine values, feminine forms: on the gender of personified abstractions

- 5. Natural sex: the attribution of sex and gender to plants in ancient Greece

- 6. Eros the blacksmith: performing masculinity in Anakreon’s love lyrics

- 7. The male body as spectacle in Attic drama

- 8. Rape and young manhood in Athenian comedy

- 9. Understanding the men in Menander

- 10. Ideals of masculinity in New Comedy

- 11. Juvenal, Satire 2: putting male sexual deviants on show

- 12. In the name of the father: procreation, paternity and patriarchy

- 13. The old Adam: Fathers and the unmaking of masculinity

- 14. The hero of our time: classic heroes and post-classical drama

- Bibliography

- General index

- Index of ancient authors