1

Managing a Global Resource: An Overview

Uma Lele

Industrialized countries tend to attach greater weight to forest and biodiversity conservation in developing countries than do the developing countries themselves, who view their resources through the lens of their own socioeconomic development.1 The weight developing countries give to conservation objectives depends on their forest endowments, population pressures, stages of resource exploitation and economic development. In forest-rich countries and forest-rich areas within countries, natural forests are often important sources of private profit, income, and employment as well as government revenues, raw materials, and “abundant” land for alternative uses, especially agriculture. Forests can be an engine of economic development, but their exploitation often is environmentally unsustainable and socially inequitable. Rent seeking, environmental destruction, and the failure of forest exploitation to meet the needs of the poor in developing countries, have been subjects of much debate.2 The perceived costs and benefits of forest conservation or exploitation differ, therefore, depending on whether they are seen from a local or global perspective.

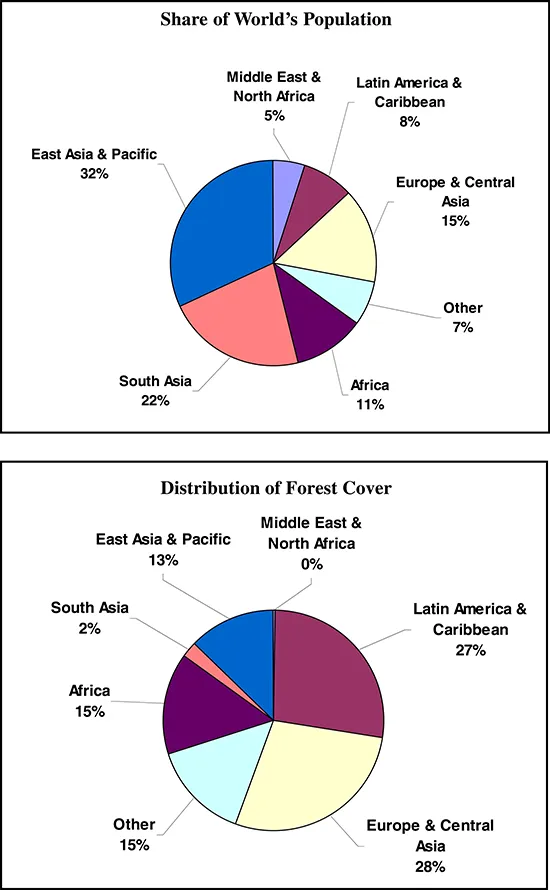

There are great differences in forest endowments between regions and within countries. The Eastern Europe and Latin America regions have the most forest per capita, while South Asia and the Middle East and North Africa region have the least (see following charts).

Besides being differently endowed, each region responds differently to when natural forests grow scarce and citizens and policymakers become more aware of the value of forests. Reform-minded leaders come forward to call for change when the stark reality of irrevocable loss sets in. Policymakers develop instruments to reconcile the dual challenge inherent in forest conservation and forest exploitation for human development. These instruments include policy and institutional reforms, changes in property rights, and incentives to support tree planting, forest regeneration, and biodiversity conservation. At that point, global environmental interests coincide with those in forest-poor regions and countries. The socioeconomic and environmental outcomes of responses to scarcity may well be positive in many respects, for example, through increased employment and income for the poor, growth of a forest industry, development of markets for environmental services including carbon sequestration and soil and water conservation. But the resulting outcome of these responses still leaves less biodiversity, although not necessarily less forest cover, than would have existed without any forest exploitation. It is fundamentally the loss of biodiversity associated with the loss of pristine natural forests, rather than tree cover per se, that seems to be the source of current debate in the international environment and development community.

Regions correspond to the World Bank regional classifications

Source: FAO State of World Forests 1999 and Human Development Report 1999

But environmental consciousness is not just high in industrialized countries. It has been increasing rapidly in both forest-poor and forest-rich countries, and is providing new opportunities for a more constructive engagement of the global community, not simply in conservation of natural forests, but in understanding the extent of synergy, and tradeoffs, of conservation with forest production and socioeconomic development, and particularly its dynamics. The accumulating evidence is making it clearer than ever that international mechanisms and financial transfers, while not sufficient by themselves, are essential to conserve the natural forests of developing countries that the global community considers to be of global value. Grant funds, if wisely applied, can help improve substantially the synergy between environmental protection and socioeconomic development, if three additional sets of steps are taken simultaneously. First, policy, institutional and technical reforms must be put in place in developing countries to ensure “managed forests”3 become fiscally, financially, economically and environmentally sustainable. Second, grant funds must be available on a sufficiently long-term basis to developing countries with expectations of clear performance indicators and clearly monitorable milestones of achievements in reforms so that domestic conservation policy and institutional arrangements in developing countries become effective and sustainable. Third, funds must be adequate, and enforcement and transfer payment methods effective, to compensate the agents of deforestation in developing countries for their legitimate opportunity costs of conservation until such time that conservation becomes sustainable. Without it, considerable biodiversity that the global community considers of value will likely be lost. (Although, as in developed countries and recent experience in Costa Rica, China, and elsewhere in some as yet limited parts of the developing world, forest cover may well increase over time after some initial decline, followed by stabilization, as lost natural forests are replaced by either planted forest or secondary forest regrowth).

The diverse circumstances and histories of individual developing countries show why even with these steps in place, a certain amount of deforestation is inevitable, particularly in forest-abundant countries at early stages of their natural resource exploitation—and why forests tend to be conserved and even expanded only in the later stages. Which forests are exploited, and for what purposes, depends among other things on agro-ecological circumstances, population densities, and the physical infrastructure that determines market access to forests. (This volume does not recount the story of deforestation in developed countries, but it is pertinent to mention that while tree cover is no longer declining in the industrialized world, old-growth forests are all but gone and what remains is still threatened with extinction because of demand for alternative uses of land and forest products.)

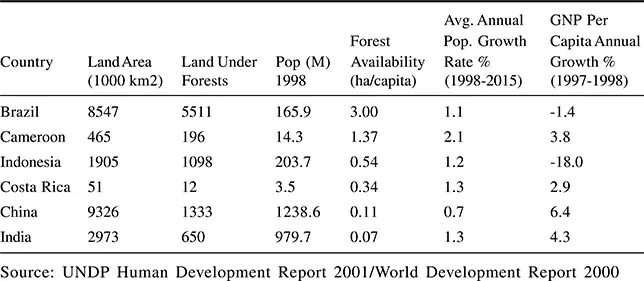

Table 1.1 provides the details of the endowments, size, and economic performance of the countries analyzed in this volume, namely, three forest-rich countries (Brazil, Indonesia, Cameroon), two forest-poor ones (China and India), and one (Costa Rica) that is now in transition from forest-poor to forest-rich due to the progressive policies it has actively pursued.

Examination of the forest policy and practices of these countries reveals the following:

As much as 65 percent of the benefits of forest conservation are global, but the costs are local, borne almost completely by the local people in developing countries.4 This means the divergence in the incidence of costs and benefits must be addressed in the design and implementation of instruments if natural forests and biodiversity are to be conserved.

The domestic and international factors and processes that lead to the loss of forest cover vary greatly among countries and need to be understood better. In-depth country analysis and cross-country comparative analysis is necessary to understand similarities and differences between and within countries and make rapid transfers of experience, knowledge and best practices. Cheaper communication and global networking now make information dissemination possible on an unprecedented scale.

Table 1.1

Relative Developing Country Endowments

-

Using the individual country as a unit of analysis is essential to understanding the policy and institutional reforms needed to reverse loss of forest cover. In many developing countries more than 90 percent of the gazetted forestland is listed as publicly owned, yet de facto property rights vary enormously between countries and over time and they tend to be poorly defined. Many of the causes of forest cover loss lie outside the country’s forest sector in demographic, policy, investment, and institutional factors. Governments (federal/central, provincial/state/regional, and local) have responsibility for formulating and enforcing (or failing to enforce) laws, fostering pluralistic institutions, including facilitating appropriate roles for civil society and the private sector and ensuring social justice. Because lack of good governance is often a problem, both de jure and de facto rules of the game vary considerably.

It is difficult to make global generalizations about the causes and consequences of forest loss. The diversity and complexity has considerable implications for how the external actors generally, and the World Bank Group especially, might address the global objectives of containing forest and biodiversity loss while helping developing countries formulate forest policies, and related policies and institutions external to the forest sector, for improving forest management in the wider developmental context.

Thus, the biggest challenge is to find policies, institutions, and incentive structures that allow for the transfer of international resources to cover the global benefits that forests provide. This must be achieved without jeopardizing the ability of developing countries to manage their forests and engage in forest production and utilization for developmental purposes. It is not surprising therefore, contrary to the expectations expressed in the World Bank’s 1991 forest strategy, that the Bank’s impact on forest sector reform in forest-rich countries was minimal. But in forest-poor countries, which were not the focus of the 1991 strategy, the Bank made important contributions. In retrospect, these contributions too turned out to be greater than expected. They occurred both through policy analysis and advice and Bank-supported investment operations. In some cases, Bank analysis and advice improved policies, built the capacity and confidence of key stakeholders and facilitated increased participation of the poor in forest management. It also established partnerships, improved forest productivity, and encouraged forest regeneration. In each of these cases, the stimulus for forest conservation and protection has come largely from the forest-poor countries themselves, rather than being externally imposed, although in several subtle ways the Bank facilitated and accelerated the internal reform process without taking credit.

The Bank’s 1991 strategy did identify a fundamental problem: national governments as well as individuals, community groups and businesses often want to realize the capital in standing trees and the land they cover, while a wider concern for the global environment presses for the conservation of forests and the protection of biodiversity. But the strategy did not address the implications of these conflicting priorities—or the implicit gap in global public and local private and community views on the management of those resources. Hence, it did not address the limitations of the World Bank’s financing instruments—its IBRD loans or IDA credits—for addressing the challenge of conservation. In a marketplace where conservation faces competition for funding from other sectors offering high social returns, conservation often loses out. Instead of addressing this problem, the Bank relied almost exclusively on the emerging Global Environment Facility (GEF) to meet the demand for action on conservation.

As the only global financing mechanism for the implementation of all existing environmental conventions,5 the GEF is clearly an important catalyst for saving the developing world’s biodiversity and conserving forests for carbon sequestration. But in the case of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), the memorandum of understanding states that CBD gives guidance on policies, strategies and eligibility to the GEF Council, which then operationalizes the convention. Owing to the lack of clarity in the convention, GEF has lacked a global priority agenda for its thrust on biodiversity conservation. GEF is supposed to finance the global environmental objectives within national development agendas and depends on the initiatives of the three implementing agencies—the World Bank, UNDP and UNEP—to generate country-level dialogue. Furthermore, the implementation of the GEF as a financing mechanism has raised complex conceptual issues about what constitutes biodiversity, and biodiversity of global significance, and hence, how to measure its loss or gain and whether incremental grant financing for a short duration, the approach currently followed by GEF, is sufficient for its conservation.6 The considerable ambiguity in the convention on biological diversity in this regard has not helped.7 Therefore, GEF’s impact is difficult to determine. Moreover, GEF has limited resources in relation to the vast financial needs for conservation in developing countries. GEF grants for forest projects during 1991 to 1999 amounted to $370 million, and it does not have a mandate to compensate developing countries for the potential loss of income from forest protection, although other GEF biodiversity programs also have impacts on forests. Therefore, GEF’s contribution must be addressed largely in catalytic terms, i.e., the extent to which it is contributing to knowledge on where, how and under what circumstances is biodiversity conservation achieved.

The Bank’s 1991 strategy failed to recognize the sheer size of this public goods dilemma: how to persuade the global community to pay landowners and forest dwellers to conserve natural forests of global significance in developing countries while dealing with the complex developmental challenge, that is, promoting the use of forests and their biodiversity to ensure economic values and incentives are established for their conservation by the nationals of developing countries themselves (see box 1.1). To have any effect on forest conservation, global climate change, or biodiversity, the required payments in exchange for conservation of the environmental values that forests and biodiversity provide to the global community are not known with any certainty. But according to one estimate, payments of $6.5 billion to $10 billion annually would be required to ensure the conservation of 600 million hect-ares of forest in Latin America that could affect the climate (Lopez 1999). Some of this area constitutes natural habitats for major biodiversity, but the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) also estimates this amount of forested area would be lost in the next 60 years (assuming 80 percent of the needed increase in food production comes from agricultural intensification on existing cropped areas). Those estimates of annual required payments are comparable to the annual funds now being sought for the global health fund for AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

While agreeing to a similar rate of payment needed per hectare, some have questioned if the overall size of payments would need to be that large, arguing that payments for averting annual current increments of deforestation on about 13 million to 20 million hectares (about $72 million to $200 million a year) would be sufficient.8

Estimates of the amount needed for biodiversity conservation also cover a wide range, from $30 billion a year for a global reserve network covering each continent to a single payment of $25 billion for a “silver bullet strategy” that would compensate the owners of lands containing particularly valuable biod...