Chapter 1

Elizabeth Chaplin

MY VISUAL DIARY

Introduction

MANY PEOPLE KEEP A WRITTEN DIARY at some point during their lives – one thinks of teenagers, anthropologists, politicians. And nowadays video-diaries are increasingly common – one thinks of ‘docu-soaps’, blogging and various forms of reality TV. A few visual artists have produced sequences of drawings or paintings in diary form (Kitson 1982; Kelly 1983). But photographic diaries are very rare, despite the fact that 80 per cent of the UK population owns a camera.1 As a social scientist, I have kept a daily photographic diary for fifteen years. This chapter describes that experience and discusses the advantages of keeping such a diary.

Most diarists focus on events that stand out in their minds from the basic routine of their everyday lives; but a few, like the eighteenth-century village shopkeeper, Thomas Turner (Vaisey 1984), dwell on the detail of that routine itself. For social scientists and historians this latter type of diary is important, because everyday routine is, by definition, what much of our lives consist of – and it tends to get forgotten. My diary aims to be of this type. But the still visual diary, unlike video and written diaries, does not present a flow of events over time. Instead, it consists of a sequence of (possibly captioned) frozen moments, each of which becomes exceptional by the very fact of being singled out. So, in the short term, a photographic diary may record a series of ‘heightened’ ordinary moments. But viewed over a longer period – say, a year – some of those heightened moments may begin to recur regularly, though in a slightly changed form; and patterns of continuity – and even routine – may become apparent.

The idea of keeping a photographic diary did not come to me out of the blue; it has a prehistory. As a social science undergraduate, I was advised to keep an intellectual diary: to save newspaper cuttings, and jot down notes on a fairly regular basis, about issues, topics and ideas that concerned me. This became a long-term habit; and in one sense the photographic diary grew out of that habit. But there were other reasons for embarking on it as well. In the late 1980s, I was researching some British visual artists, and felt the need to ‘get closer’ to them: to share their experience of making aesthetic visual artefacts.2 The idea of a keeping a photographic diary seemed to fit the bill. Besides constituting a formal visual project on the world, it would record my contacts with the artists. In addition, Goffman had made some intriguing remarks (1979: 20) about a photograph being unable to record routine, which I wanted to explore. I started my photographic diary on 7 February 1988. Apart from the occasional missed day, and some slightly longer periods when its immediate purpose had become rather unclear, I have kept it up ever since.

I soon found that photographs lead to the heart of social science theory. For while they do record – indeed they discover things our minds have failed to consciously register as we go about our lives – they never record neutrally. A photograph is ‘taken’, but at the same time, ‘made’. It does constitute a trace, but how that trace is visually presented is the result of many subjective – often ‘aesthetic’ – decisions. And how that photograph is viewed is not a simple matter either. A photograph is almost never viewed purely ‘as a photograph’; we tend to focus on the content of the image, and ‘what it means’ seems to vary according to the context in which it is viewed. And again, the notion of ‘context’ itself conjures up a veritable range of theoretical possibilities.3 Thus, when social scientists take/make photographs on a regular basis, they become unavoidably implicated in a theoretical maelstrom. And involvement in that maelstrom is no purely academic matter when fuelled by a fascination with photography and photographic images, because what is also unavoidably involved is a consideration of that most powerful of social institutions, the media.4

The career of my visual diary

Year 1: 1988

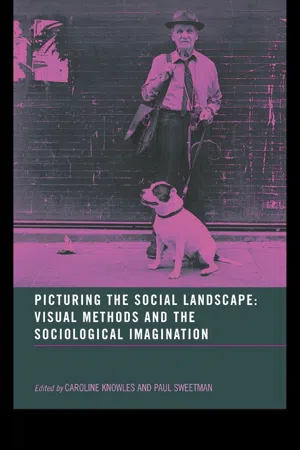

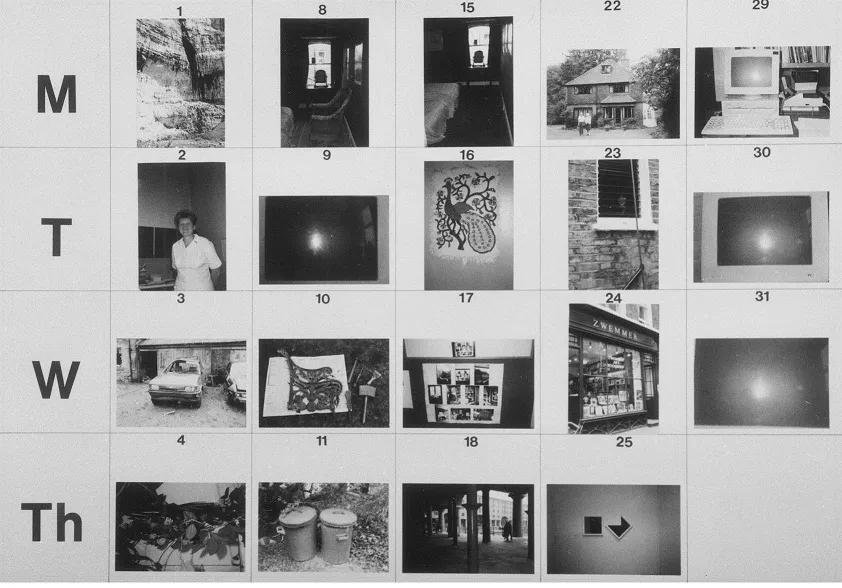

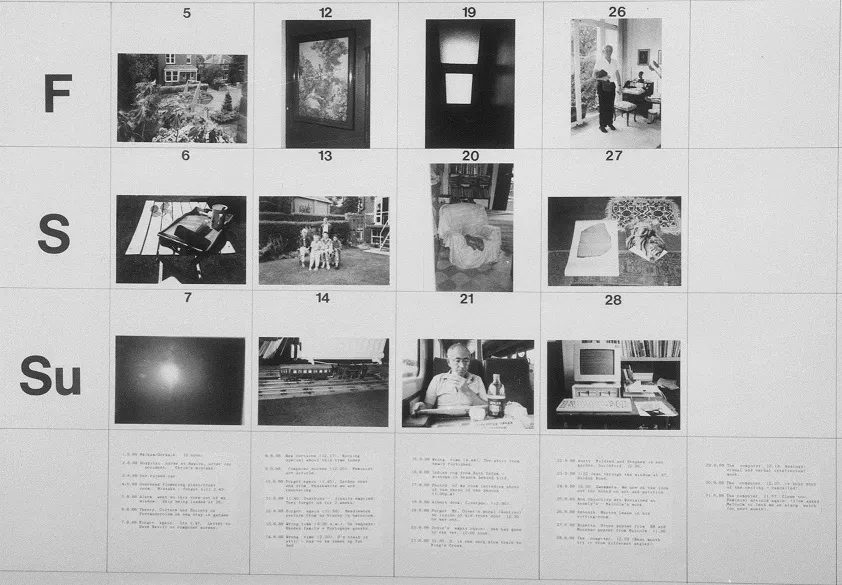

Goffman has remarked that routine behaviour and action cannot be shown in a photograph. On the other hand, keeping a diary is a matter of routine. My original project was to attempt to show routine via a sequence of daily photos. But I soon realized that that my ‘visual diary’ would – more accurately – need to consist of a daily photograph accompanied by a short descriptive verbal passage. Photographs do not speak for themselves, and at a basic contextual level it is words which give meaning to images (Burgin 1986). So I decided to produce one captioned photograph per day for a whole year, with the aim of exposing traces of routine in my life. However, soon after I started I found it necessary to construct a rule about what to photograph and when to photograph it – another verbal intrusion into the ‘visual diary’. And as the months passed, I became increasingly taken up with inventing rules which narrowed down the choice of what to photograph. Plate 1 shows August 1988, when the photograph was taken ‘straight ahead’ at 12 noon each day, but any rule seemed to contain an element of arbitrariness (for example, ‘straight ahead’ does not specify the height at which the picture is to be taken).

Plate 1 August 1988. Visual diary. Coloured photographs mounted on board.

However, half way through the year, the offer of an exhibition of the year’s visual diary at Leeds University art gallery turned the project into an aesthetic one. So now I really was ‘getting closer’ to my research subjects, although, by the same token, this development pushed the already modified Goffman-related question slightly out of focus. I produced a set of twelve boards, each containing a month’s photographs and captions, together with the monthly rule. Having been shown for three months as art, the same set of boards was then displayed as visual anthropology at the annual social anthropology conference. The change of context gave the work an entirely different meaning: the daily captioned photographs were now seen as ‘anthropology at home’; this – despite the newly acquired social scientific context – was not quite the same thing as a focus on routine. The importance of contextualization would stay with me into Year 2.

Year 2: 1989

This year I was working closely with the artists. I wanted to produce photographic images which were visually analogous to their geometric abstract work but also explored the notion of context. The fall of the Berlin Wall was a prominent news item, and photographs of the wall were in all the newspapers. This triggered the idea of photographing a different wall each day. I started to produce a daily close-up of a wall, and, in addition, a contextualizing view of it. The close-ups of walls helped me to address some of the artists’ concerns because I was producing images similar to their geometric abstract work, yet with a rather different theoretical underpinning. The contextualizing views showed the work that ‘background’ does in supplying meaning for a foreground object, transforming it from an aesthetic composition to a social situation. But after nine months, I began to miss recording people and social events, and viewers evidently felt the same, because they just flicked through the prints. So I stopped photographing walls, and began to address other current concerns: the position of the researcher in the research, and the feminist concern with voyeurism. My photographs became much more self-consciously made, as I attempted to show a trace of myself, the photographer, in each photograph that I produced. This trace consisted either of a shadow, a footprint, a reflection (in water or a mirror) or an actual hand or foot. The photographs became rather elaborate and unconventional: I found I was stepping over the borderline between record and aesthetic composition in a different way from in the previous year.

Year 3: 1990

This year I acquired a new camera with the date built in; so one aspect of the daily recording process was transferred into the technology of the camera. I became increasingly dissatisfied with the part played by the commercial processors in producing the daily image. I wanted greater control, so I changed from colour to black and white film, and started processing it myself. Once I had set up my darkroom, and was liberated from the expense of having the film commercially processed, I took several photographs each day. But I then faced the problem of which negatives to print and which to ignore, since printing was very time consuming. For a while, the project consisted of selecting negatives to print on a random basis; then of selecting according to a rule (e.g. every fourth negative). But the lure of the ‘good’ negative soon overcame this, and I began to print up the most promising ones. The subject matter became more various: family, research project, holidays, curiosities, visual compositions. In fact, more time was now being spent on learning how to produce black and white photos than on sociological concerns.

However, I exhibited a visual and verbal analysis of the diary to date at the annual British Sociological Association conference, and my daily photograph of 4 April 1990 was a record of that display.

Year 4: 1991

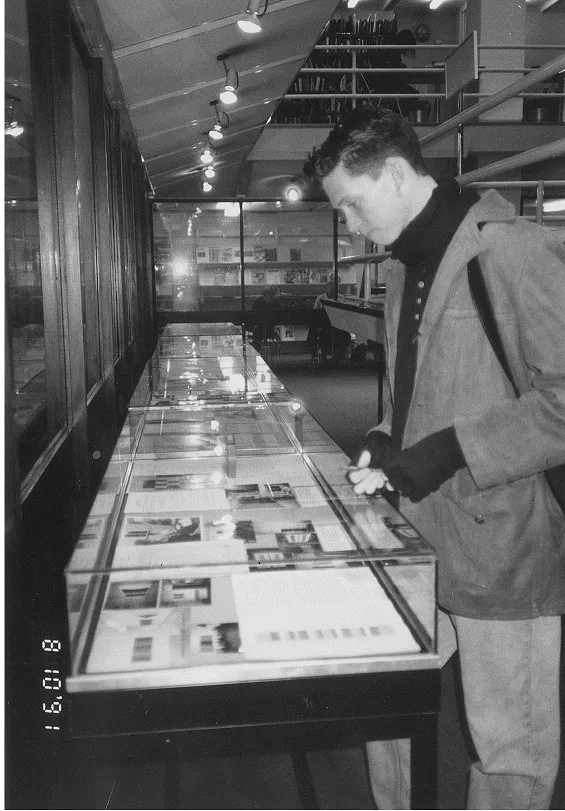

I carried on working in black and white, but focusing on improving technical skills was still taking precedence. I had some of the current diary exhibited at York University Library, alongside the work of my artist research partner. This daily photograph (Plate 2) shows a student looking at the exhibition. Later in the year, I reluctantly changed back to colour and commercial processing (for good), because the processing was taking up too much time. ‘Year 1’ was exhibited at Wakefield Museum, alongside an artist’s visual diary drawings of the same year. The exhibition thus consisted of a double-entry visual diary.

Plate 2 8 October 1991. Visual diary. Student looking at visual diary exhibition in J. B. Morrell Library, University of York. Black and white photograph.

Years 5–7: 1992–4

During this period, I became involved with the British Constructivist artists’ women’s group, and documented preparations for our exhibitions at the Mappin Gallery, Sheffield, and at Warwick University. One of these exhibitions included my own artwork postcard (Plate 3) – a collage of various diary entries. In Year 7 (1994) I made an artwork, ‘Postcard Rack’, which displayed items from my photographic diary. This was again exhibited with the women artists’ work. I had become accepted as an artist, as ‘one of them’; and my photographic diary had become the raw material from which my artwork was constructed. I used the project for my teaching on an M.A. course at the University of York, UK (as I had done each year until now), and photos of the students at seminars became part of ‘Postcard Rack’.

Year 8: 1995

I loosened ties with the artists, and helped produce the Open University course, Culture, Media and Identities. As a result, semiotics and cultural studies began to influence my approach: for example, I acquired a certain self-conscious awareness of the semiotic significance of the image. But the actual day-to-day visual diary was becoming less important – which indicates that a semiotic approach, though appropriate to the analysis of found images, may present problems when applied to one’s own current daily photographs. Mine tended to dry up. Theory took precedence, and the image receded into becoming a judiciously chosen illustration.

Plate 3 The Countervail Collective, 1992. Montage of visual diary colour photographs.

Years 9–11: 1996–8

During this period, my visual diary merely ticked over. I was ‘just’ photographing items of daily interest, sometimes several a day, and I sometimes forgot a day. This was partly because I acquired a digital camera in Year 9 and was beginning another visual project which did not seem to relate to the diary. It was also partly because I was no longer researching the artists, and writing about semiotics had dampened the project. At this stage, having kept the diary up for so long, it just see...