![]()

Chapter 1

General Introduction

Behavioral Classification of Drugs

If the purpose of administering drugs is to change behavior, then it is useful to have a behavioral classification of drug effects to make it easier to remember the applications of different drugs and to understand the relationships between them. The following behavioral classification system, based on the one presented by Julien (1992), is suggested as a way of organizing the different drugs relevant to clinical psychopharmacology. Remember, however, that: (a) drugs have been included in a particular category because of their primary use and, if side effects are considered, many drugs could be included in several categories; (b) drug effects on behavior usually change as a function of dose and therefore some drugs could be included in other categories at some doses; and (c) drugs that have similar behavioral effects may differ in chemical structure and in the effects that they have on the nervous system (Julien, 1992). Antidepressant drugs have been excluded from “CNS stimulants” because, for the most part, they do not act as stimulants in nondepressed individuals and because they have a “mood-elevating” effect in depressed individuals rather than a general stimulant effect (Julien, 1992; see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1

Behavioral Classification of Drugs

CNS Depressants or Sedative-Hypnotic Compounds

(Clinical applications: anxiety disorders, insomnia, epilepsy, anesthesia)

- barbiturates (e.g., pentobarbital)

- benzodiazepine anxiolytics and hypnotics (e.g., diazepam, triazolam)

- atypical anxiolytics (e.g., buspirone)

- anesthetics (e.g., chloroform)

- alcohol

CNS Stimulants

(Clinical applications: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [ADHD], narcolepsy, weight loss)

- amphetamines (e.g., dextroamphetamine)

- cocaine

- caffeine

- nicotine

Antidepressants

(Clinical applications: some anxiety disorders, unipolar depression, and other affective disorders, chronic pain)

- tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., desipramine)

- monoamine oxidase inhibitors (e.g., moclobemide)

- atypical antidepressants (e.g., fluoxetine)

Antipsychotics

(Clinical applications: schizophrenia, mania, and other psychoses)

- phenothiazines (e.g., chlorpromazine)

- butyrophenones (e.g., haloperidol)

- thioxanthines (e.g., flupentixol)

- atypical antipsychotics (e.g., clozapine)

- lithium

Analgesics

(Clinical applications: relief of pain)

- opioids (e.g., morphine, heroin)

- aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- acetaminophen

- adjuvant analgesics

Psychedelics and Hallucinogens

(Clinical applications: analgesic potential of cannabinoids)

- lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD)

- phencyclidine (PCP)

- cannabinoids, etc.

Neurological Drugs

(Clinical applications: epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease, spasticity; local anesthesia)

- antiepileptic drugs (e.g., carbamazepine, phenytoin, sodium valproate)

- anti-Parkinsonian drugs (e.g., levodopa, bromocriptine)

- antispasticity drugs (e.g., baclofen)

- local anesthetics (e.g., procaine)

Note: Modified from Julien (1992).

Classification of Psychological Disorders

Throughout this book, the psychological disorders discussed are classified according to the 1994 edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-1V; American Psychiatric Association, 1994).

Introduction to General Pharmacology

Definition of Terms

Pharmacology is the study of the effects of drugs on the body. Given the broad nature of its subject area, pharmacology includes a number of subdisciplines. Neuropharmacology is the subdiscipline devoted to the study of the effects of drugs on cells of the nervous system. Psychopharmacology is the subdiscipline devoted to the study of the effects of drugs on psychological processes and behavior. Clinical psychopharmacology is a subdiscipline of psychopharmacology concerned mainly with the use of drugs to treat abnormal behavior.

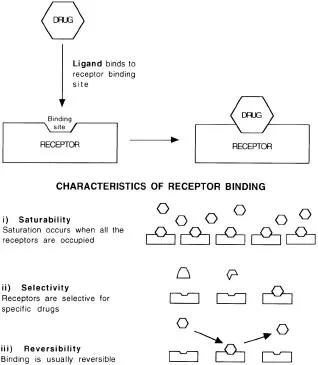

In this book we define the term drug as “any chemical agent that affects living processes” (Benet, Mitchell,&Sheiner, 1991a, p. 1). This broad definition includes not only exogenous chemicals that are ingested deliberately or inadvertently but also endogenous chemicals such as neurotransmitters and hormones. What all drugs have in common is that they elicit their response by acting on cellular receptors. These receptors can take many forms.

Pharmacokinetics is the study of the absorption, distribution, and elimination of drugs, that is, “what the body does to the drug” (Benet et al., 1991a, p. 1). Pharmacodynamics is the study of the action of drugs at cellular receptors, that is, “what the drug does to the body” (Benet et al., 1991a, p. 1).

Pharmacokinetics

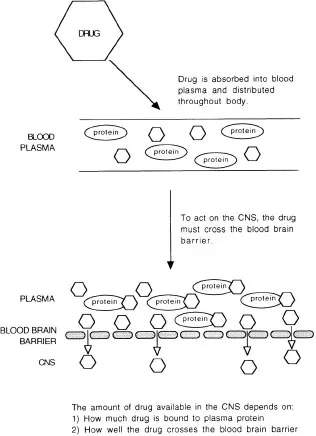

Drug absorption is the process by which a drug gets from the site of administration to the blood plasma (the fluid of the blood minus the red and white blood cells; blood serum is the plasma minus the blood protein, fibrinogen, see Fig. 1.1). There are many different routes by which drugs may be administered. In human clinical psychopharmacology, oral administration is the most common route. The following is a brief summary of the characteristics of different routes of administration:

Fig. 1.1. Schematic diagram of the processes involved in drug absorption and distribution.

1.oral/swallowed: absorption from the gastrointestinal tract. This route of administration is convenient but unreliable. Most of the absorption is from the large surface area in the small intestine and if the stomach is full, absorption is delayed (hence the reduced effects of alcohol on a full stomach). Many drugs that are administered orally are subject to extensive first–pass metabolism by the liver (i.e., once absorbed from the small intestine, the drug will enter the liver via the portal circulation before entering the general systemic circulation and being distributed throughout the body). Consequently, the drug may be extensively metabolized before it reaches the target receptors.

2.oral/sublingual: under the tongue. This route results in fast absorption into the systemic circulation, bypassing the gastrointestinal tract and therefore avoiding absorption problems and first-pass metabolism in the liver. This route is useful for patients who are likely to vomit and lose medication that was swallowed.

3.rectal: absorbed directly from the rectum. This route partially avoids first-pass metabolism by the liver and is also used for patients likely to vomit and lose swallowed medication.

4.epithelial: for example, absorption through the skin. Most drugs are poorly absorbed from unbroken skin because of its low lipid1 solubility. However, in some cases, this route may be useful for patients likely to vomit.

5.inhalation: enters the bloodstream very rapidly from the lungs. There are no absorption or first-pass metabolism problems with this route of administration; however, it is potentially dangerous because it is so fast and direct.

6.injection: several possible routes: under the skin (subcutaneous [SC]); into muscle (intramuscular [IM]); into a vein (intravenous [IV]). Drugs administered SC or IM exert their effects more quickly than those administered orally (i.e., swallowed) but the rate of absorption depends on the rate of blood flow through the injection site. The IV route is the fastest systemic injection route and the most certain in terms of obtaining the desired concentration of the drug in the blood plasma. Because the drug is injected directly into the systemic circulation, there are no problems with absorption or first-pass metabolism. However, as with inhalation, the IV route is also potentially dangerous because it is so direct.

Bioavailability is a term used to refer to the degree to which a drug reaches its target receptors or a biological fluid (e.g., blood plasma) from which the target receptors can be reached (Benet et al., 1991a; see Fig. 1.2).

Fig. 1.2. Schematic diagram illustrating the properties of receptors.

Once the drug has entered the blood plasma, it is distributed throughout the body via the systemic circulation. How much drug will be available to bind to receptors on neurons in the central nervous system (CNS) depends on how well the drug crosses the blood brain barrier—a term used to describe the low permeability of capillaries that supply the CNS with blood—and the amount of drug that binds to blood proteins2 (and therefore cannot bind to CNS receptors; see Fig. 1.1). Some drugs that are used experimentally cannot be used clinically because they cross the blood brain barrier so poorly that they can only be administered directly into the brain. Other drugs bind extensively to blood proteins and therefore much of the drug does not cross the blood brain barrier.

After the drug molecules3 have acted on receptors in the CNS, they are eliminated from the body. The term elimination refers to the two processes by which drugs are eliminated from the body: (a) metabolism, performed mainly (but not exclusively) by the liver; and (b) excretion, performed mainly (but not exclusively) by the kidneys. Clearance is the term used to describe the ability of the body to eliminate a drug. Elimination half-life is the time required for the concentration of the drug in the body to decay to 50% of the initial peak concentration. Drugs usually stay in the body for approximately four to five half-lives.

Pharmacodynamics

Once the drug has been absorbed into the systemic circulation and distributed throughout the body, the effect that the drug elicits depends on the extent to which it acts on the target receptors (in the case of psychoactive drugs, in the CNS). It is important to remember that drugs are not distributed only to the ta...