- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Published in 1998, Adolescent Gangs is a valuable contribution to the field of Counseling and School Therapy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Adolescent Gangs by Curtis Branch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Clinical Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART

I

COMMUNITY-BASED INTERVENTIONS

The three chapters contained in this section represent an interesting cross section of views on how to work with gang adolescents and issues that should form the basis of the intervention. Gonzalez suggests that gangs are in the midst of redefining themselves. The transformation, he thinks, from outsider to responsible community members, has not been without problems. From his perspective, the most obvious evidence of the emerging change can be found in the names and classification (i.e., street organizations versus gangs) that many organizations are choosing for themselves. The reluctance to continue to use gangs as a self-descriptor appears to be related to the members recognizing that gangs have a pejorative connotation in the larger social context. It appears, based on this logic, that gang members have been listening to what others have been saying about them. To hasten their group identity transformations, street organizations are moving in the direction of being capitalists and active participants in their communities’ economic life. Branch (1997) suggests that the concern about what others think of them drives much of the behavior of members of street organizations. Even in their states of disengagement with the communities in which they reside, gangs and communities have a dynamic relationship.

Doucette-Gates’ approach to gang-affiliated adolescents, as represented in this volume, takes a bit of a traditional psychological approach. She explores the concept of future time perspective and how it influences decisions that gang adolescents make in the here and now. Implicit in her approach is the idea that gang adolescents have an inner psychological life to which they have access. The inner life is nurtured by the quality of the ecologies in which they function. Young people growing up in settings of economic poverty, poor quality education, and disjointed family life are at high risk for having limited vision of hopes of overcoming such adversities. The outcome is that they tend to live in the here and now, not being certain that they will live to have “a future.” The overarching premise of the Doucette-Gates research appears to be that interventions need to be sensitive to the environs of the consumers, on a behavioral and cognitive level. She strongly suggests that perhaps the first step to making sustained interventions into the lives of gang adolescents and other at-risk youngsters is to get them to look beyond the here and now (i.e., dream, hope). Of course, that is no small feat but one which must be accomplished if there is to be any movement beyond current behaviors and thinking.

Issues related to here-and-now functioning among many urban African American males are articulated in Quamina’s essay. The work is slightly different from its companion pieces in that it is heavily dependent on anecdotal data. The result is a decrease in objectivity and generalizability. Even with these limitations there is still value in the presentation. It articulates a set of questions concerning how and why African American males learn the scripts that they often display (i.e., emotional distancing, congregating in sets, being players). Quamina thinks that schools could play a vital role in helping young men explore other ways of being. His examination of the role of schools in fostering the patterns of behavior noted speaks to the issue of early socialization being the foundation upon which other patterns are built. From a developmental perspective, such an inquiry leads back to the question of what if the rudiments of prosocial developments never emerge. What then? Does the child simply exhibit arrested development and drop out of the larger society (i.e., withdraw into sets), or does he try to get his affiliation needs met by engaging in self-defeating self-destructive behaviors? Or, does he simply float along in life waiting for others to articulate his needs?

Three themes appear to emerge from these three chapters: time perspectives and how they influence the choices that young people make; questions of self-definition; and how do scholars or practitioners gather information about gang adolescents and for what purposes.

“Time” is a psychological dimension that is often neglected in understanding research. The concept, as used here, refers to time in the life of the subject (i.e., developmental moments); historic era (i.e., late 20th century); and point in an ecological maze which intersects the multiple systems of which the subject is a part, all simultaneously. Let me briefly explain this last idea.

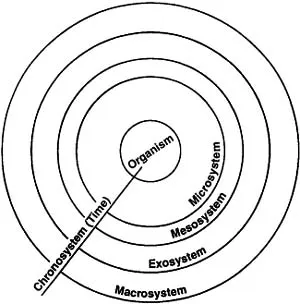

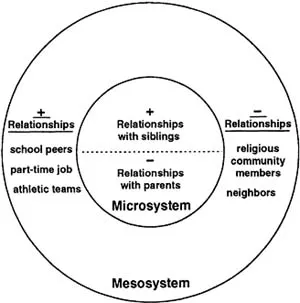

Bronfenbrenner (1979) has suggested that all individuals are members of several systems at the same time. See Figure I.1. The point in time that cuts across all of the systems is what is being considered here. For example, an adolescent who is engaged in psychologically individuating from parents may be experiencing loss in the microsystems which involve parents while he is experiencing attachment and connection in microsystems involving friends and peers. Likewise mesosystems (i.e., school-church; home–community) may be represented with a mixed picture of positive experiences and negative or positive experiences or both). Figure I.2 gives a detailed representation of the hypothetical case.

The point here is that at any given moment in time an adolescent may be receiving a vast array of messages about himself and the worlds in which he functions. A partial determinant of what will be the nature of the messages delivered to the adolescent is where the point in time is located in the system in which it is occurring. Are the friendships in the microsystem just beginning or are they long-standing relationships? It seems to me that the exact location of time in the life of a systemic relationship determines to a large degree the type of message given and how important it will be perceived to be by the adolescent who is the recipient. The three authors represented in this section seem to agree that negative experiences from ongoing systems (i.e., neighborhoods, school) undoubtedly are important to adolescents, evidenced in part by the youths being very reactive to them. Remember that society has created an image of “gangs” that is negative and pejorative. Gonzalez suggests that because of that image, many of the groups so classified have opted to call themselves by another label. Quamina notes that the African American males whom he observed likewise are intensely affected by social images of them. The result is that they appear to drop out, in search of a place in which they will be viewed more positively perhaps. Doucette-Gates offers a similar observation. The critical difference in her statement and Quamina’s is the consistency of message across time. The young men discussed by Quamina apparently received “the word” early on and made an adjustment in their behavior and attitudes which caused them to form their own subset. They could conceivably be thought of as dropouts who are still present. The youngsters in Doucette-Gates’ study have received negative messages about themselves and their relationship with the larger society. Like Quamina’s subjects they continue to attend school but clearly are not as positively impacted by the experience as one would hope. Instead they internalize beliefs that suggest that there is no “future” for them. The “future” is “now.”

FIGURE I.1 Ecological Systems Map

FIGURE I.2. Mixed Relationships Across Ecologies

Time, and timing, are critical elements in the lives of all of the subjects described in the first three chapters. The time in the lives of the subjects in which the messages about possibilities and the future are given is critical. The authors have suggested that the timing of negative messages to their subjects has significant implications for how they can potentially respond to the messages. Gonzalez notes that many of his subjects have responded by simply renaming themselves (i.e., gangs are now street organizations). Quamina’s subjects appear not to be as creative. They do not redefine themselves; rather, they appear to internalize the messages given to them about themselves. The separation from the larger context in which they have been marginalized could be seen as an attempt to adopt behaviors that will allow them to continue to feel good about themselves but not believe what others (i.e., teachers) have said about them. In both cases it seems to me that the subjects are attempting to cope. They live in communities that they perceive to be less than supportive and affirming. In response to this interpretation they make some decisions about how they want to conduct themselves. Here time(ing) is all important!

If the negative messages occur early in the development of the individual such that he does not have the cognitive skills or political savvy to interpret the messages as negative, then he is likely to internalize them. The result of such behavior is often that the subjects come to see themselves through the eyes of someone else, all the while thinking that the vision is their own. Examples of such often occur with youngsters and their families who are overly reliant on the larger society and its major institutions (i.e., schools) for directions. Economically poor families are especially at risk for such behavior. On the other hand, if the negative messages about self are received by a young person after he has developed significant microsystems and mesosystems through which he evaluates the world, the outcome is likely to be very different. Consider again, for example, Gonzalez’s subjects who are astute enough to critically appraise how others call them as valid and relevant to their lives.

In the same way that time is important for understanding the occurrences of events, it is also important for understanding how and when young people respond to socialization messages. Within the psychological literature, this is usually described as response latency or delay of gratification or both. Both of these concepts are particularly important for understanding the lives of gang adolescents and other at-risk youth.

The traditional literature on delay of gratification has suggested that young subjects and persons of color tend to exhibit a limited capacity for delay of gratification. Instead they prefer immediate rewards, even when they are small and of limited value, to delayed, more substantial rewards. Boys of multiple racial and ethnic groups consistently show less capacity for delay of gratification than girls. The delay of gratification research paragraph has usually required subjects to indicate whether they want a small reward immediately or if they opt to wait for a larger reinforcement later. Mischel and his colleagues (Mischel & Baker, 1975; Moore, Mischel, & Zeiss, 1976) showed that a revision of the typical delay of gratification dilemmas also produces patterns unlike those mentioned above. They have shown that involving the subjects in identifying the rewards and partial schedules of reward (as opposed to all or nothing, now versus later) also has an impact on results. These issues appear to be potentially useful in understanding the dynamics of the behavior of gang adolescents and their urge to acquire “things” (i.e., rewards) in a timely, perhaps even compulsive, fashion. Let me explain.

The quest for things, material and psychological, is what appears to drive the behavior of many gang adolescents. They want to be like others, as measured by level of social acceptance, indicated by having friends and all of the material things that others possess. Branch (1997) has shown that when asked to rate themselves on measures of values and sociability, gang adolescents were not different from nongang adolescents on the need or desire for social acceptance and related values. He reasoned that the marginalized status that many gang adolescents have thrust onto them does not diminish the gang member’s need to be accepted. One way in which gang adolescents have attempted to force society to accept them is by acquiring and even flaunting the same material possessions that they assume to be emblematic of success in the larger world. The result is adolescents being obsessed with driving new and expensive cars and living life in the “fast lane.” Now back to the issue of delay of gratification.

The gang adolescents who long to acquire the material symbols of success often have a big choice to make: work hard at socially sanctioned activities (i.e., doing well in school, being a superstar athlete or entertainer, etc.) and eventually acquiring the “good life,” or engaging in illegal activities (i.e., drug trafficking, etc.), which may lead to immediate rewards. Inherent in this dilemma is also the gang member’s sense of hope and tie perspective. Doucette-Gates (this volume) points out that for many adolescents, there is no hope because their past has been so bleak and impoverished. She suggests that such youngsters are only concerned about the here and now. Long-range goals such as going to college and playing on a professional sports team are nonsensical. For many of the youngsters described by Doucette-Gates, the future is now. All energies should be invested in acquiring all that they can (i.e., material things and psychological relationships) in the here and now. One might be tempted to interpret such behavior as a lack of a capacity for delay of gratification. Consistent with the historic articulation of the concept such an interpretation would be correct. However, it would only answer part of a very important and complex set of questions, namely, How did they come to internalize the values that they express? Why is it important that they are respected and accepted by others, especially the others who have marginalized the gang? What role does the social context in which the adolescents have lived play in shaping their delay of gratification response pattern?

The question of how gang adolescents evolve into who they are in the here and now has been largely ignored by scholars. Jankowski (1991) offers a brief exploration for gang behavior by suggesting that gang members express a high level of defiant behavior, which places them in conflict with the society in which they live. Many adolescents acknowledge that their families and communities reject them, partly because of their own defiant personality style. In order to overcome the rejections, according to Jankowski, many adolescents seek out others like themselves, which ultimately gives rise to gangs. While this explanation is believable, it still does not explain the “how” of the process. How do rejected adolescents decide that the “problem” is with others and not with them? How do defiant personality types decide that they really do want or need to be with others? And perhaps most ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I Community-Based Interventions

- Part II Specialized Agency-Based Interventions

- Part III Mental Health Interventions

- Part IV Summary, Conclusions, and Recommendations

- Index