![]()

Drepung Monastery, Lhasa,Tibet

Photo: P.N.Owens

![]()

An introduction to mountain geomorphology

Philip N. Owens and Olav Slaymaker

1 The importance of mountains

Few would argue with the assertion that mountains are some of the most inspiring and attractive natural features on the surface of the Earth. Mountains have attracted mystics, artists, thinkers, scientists and tourists through their aesthetic appeal. Visually, mountains dominate the landscape. Mountains, such as Mt Kailash in western Tibet, have also been a source of religious and spiritual inspiration. They have affected millions of people, both those living in mountains and also those far removed from them (Ives and Messerli, 1999).

The fragility of mountain areas and their likely sensitivity to future changes in land use, management and climate have become increasingly apparent. Three recent events have brought mountain issues to world attention and initiated major scientific research programmes. In 1973, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) included mountains as one (Project 6) of the original twelve components in the Man and Biosphere (MAB) programme (Ives and Messerli, 1999). Subsequently, mountains were featured at the UN Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), or Earth Summit, in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in 1992, with Chapter 13 (‘Managing fragile ecosystems: sustainable mountain development’) becoming part of Agenda 21. Chapter 13 states:

As a major ecosystem representing the complex and interrelated ecology of our planet, mountain environments are essential to the survival of the global ecosystem. Mountain ecosystems are, however, rapidly changing. They are susceptible to accelerated soil erosion, landslides and rapid loss of habitat and genetic diversity … As a result, most global mountain areas are experiencing environmental degradation. Hence, proper management of mountain resources and socio-economic development of the people deserves immediate action (United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), 2003).

The MAB programme and the UN Earth Summit provided a springboard for the development of a variety of research groups and institutes (e.g., the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), the Mountain Forum and the International Mountain Society), reports and publications that reviewed the state of the world's mountains (e.g., Mountain Agenda, 1992, 1997; Stone, 1992; Price, 1995; Messerli and Ives, 1997) and specialist journals (e.g., Mountain Research and Development). A useful review is provided by Ives and Messerli (1999).

More recently, 2002 was declared International Year of Mountains by the United Nations General Assembly. This declaration stimulated unparalleled interest in all aspects of mountains and resulted in numerous scientific conferences, workshops and publications (including this book). This momentum is continuing, as 2003 has been declared International Year of Freshwater and mountain environments feature prominently in many of the activities. Thus, with the dawn of the twenty-first century, mountain environments are at the forefront of world attention.

2 What is a mountain?

Although visually the identification of a mountain may appear simple, there is still no single definition of what constitutes a mountain. While the high mountain peaks, such as those in the Himalaya, Andes and European Alps, are clearly mountains, there is uncertainty associated with much smaller mountains (such as the Maya Mountains of Central America) and with high-elevation systems of limited relative relief (i.e., the difference between the maximum elevation of a peak and the elevation of the surrounding land). Thus, many scientists (e.g., Meybeck et al., 2001) would argue that high-elevation plateaux such as the Altiplano of South America and the Tibetan Plateau are not mountains. Similarly, older, and consequently lower, mountain ranges, such as the Appalachians in the USA, the Urals in Europe and the mountains of Scotland, are not included in many classification systems that are based solely on altitude.

Many published works on landforms in general, and mountains specifically advocate a definition of what constitutes a mountain (e.g., Fairbridge, 1968; Goudie, 1985). Good reviews of early definitions are given by Strahler (1946) and Gerrard (1990). In the German literature there is a clear distinction made between ‘hochgebirge’ (high mountains), ‘gebirge’ (mountains) and ‘mittelgebirge’ (uplands and highlands) (Troll, 1972, 1973). From a geomorphological perspective, Barsch and Caine (1984) propose that there are four characteristics of mountain terrain that are important:

1 elevation;

2 steep, even precipitous, gradients;

3 rocky terrain; and

4 the presence of snow and ice.

Not all of these characteristics apply to high-elevation plateaux. Troll (1972, 1973) and Barsch and Caine (1984) believe that high mountains are also characterized by:

1 diagnostic vegetative-climatic zones;

2 high potential energy for sediment movement;

3 evidence of Quaternary glaciation; and

4 tectonic activity and instability.

High precipitation, low temperatures (and hence typically snow and ice, at least seasonally), internal diversity and variability, infrequent but intense episodic activity, and existence in a metastable state are often associated with mountains in general.

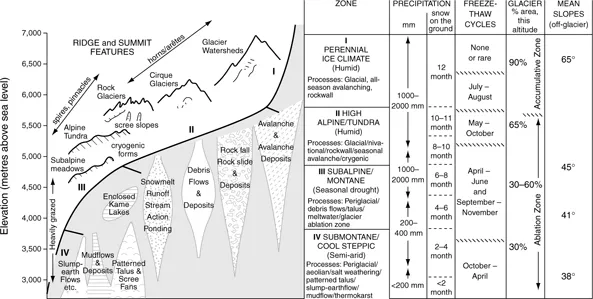

Figure 1.1 shows the altitudinal distribution of environmental variables in relation to prevalent geo-morphic processes, based on the Central Karakoram. It illustrates well the relations between elevation, vegetative-climatic zones (and, by association, soils and hydrology), landscapes and geomorphic processes. There are, however, local and regional variations in these relations that reflect, in part, variations in climate (i.e., incoming solar radiation, precipitation) and regional topography and tectonic setting.

There are, no doubt, other attributes that are characteristic of mountains, the significance of which will depend on the scientific questions being asked. It is easy to get bogged down with the issue of establishing an all-encompassing definition, which may ultimately be elusive because of the huge variation of mountain types and forms and the inherent complexity of their features. There are probably greater research questions and environmental concerns in mountain areas to which geomorphologists should turn their attention.

Figure 1.1 Altitudinal distribution of environmental variables and geomorphic processes in the Central Karakoram

Source: from Hewitt (1989), reproduced with the permission of Gebrüder Borntraeger Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart.

3 Classification systems

One of the simplest mountain classification systems was developed by Fairbridge (1968) and is based on scale and the degree of continuity:

1 a mountain is a singular, isolated feature or a feature outstanding within a mountain mass;

2 a mountain range is a linear topographic feature of high relief, usually in the form of a single ridge;

3 a mountain chain is a term applied to linear topographic features of high relief, but usually given to major features that persist for thousands of kilometres;

4 a mountain mass, massif, block or group is a term applied to irregular regions of mountain terrain, not characterized by simple linear trends; and

5 a mountain system is reserved for the greatest continent-spanning features.

Table 1.1 further illustrates this classification system according to common North American usage and is based on examples of mountains in British Columbia, Canada. Mountains can also be classified according to, among other things (cf Slaymaker, 1999; Yamada, 1999):

1 tectonic framework;

2 climate;

3 hydrology;

4 geomorphology;

5 degree of anthropogenic alteration; and

6 morphometry.

Table 1.2 provides an example of a classification system based on tectonic setting. Further information on, and examples of, the relation between mountain environments and tectonic settings is provided by several of the chapters in this volume, including those by Owen, Ollier, Williams and Onda. For reviews of other classical classification systems, which are generally based on tectonic setting and evolution, and denudational...