eBook - ePub

School Leadership and Administration

Adopting a Cultural Perspective

- 250 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This text calls for a broader approach to comparative educational administration: one which uses culture as the principle means of analysis. The articles collected by Allan Walker and Clive Dimmock detail the educational practices and outcomes of other systems while taking into account the mediating influence of culture. In this way, these essays stress the specific aspects of the cultures studied, and map out common ground for the study of administrators' values, beliefs, and actions.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access School Leadership and Administration by Allan Walker,Clive Dimmock in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education General1.

Cross-Cultural and Comparative Insights into Educational Administration and Leadership

An Initial Framework

ALLAN WALKER AND CLIVE DIMMOCK

Educators and politicians in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Japan and Korea expound the necessity for their East Asian school systems to become more like those in the West. They complain that there is too much rote learning, uniformity, and standardization and too little emphasis on creativity, diversity, and problem solving. In addition, competition is fierce for scarce places in elite schools and universities, leading to unfulfilled ambitions and wastage of talent among the high proportions of young people failing to gain entry. Meanwhile, their counterparts in North America, Australia, and Great Britain look in the reverse direction to these same East Asian countries and wonder what they can learn from the superior academic results of East Asian students on International Achievement Tests in mathematics and science (Atkin & Black, 1997).

This relatively new phenomenon—a reciprocal interest of East and West in each others school systems—characterized much of the 1990s. Other factors, besides those mentioned, fuelled the tendency to look beyond national boundaries for answers to educational problems. While many developing countries have for some time looked to Europe and North America for their policy models, what was particularly new about the 1990s was the interest taken by the developed countries, such as the United States and United Kingdom, in the school systems of East and Southeast Asia (Dimmock, 2000).

In this chapter, we affirm that internationalism as an educational phenomenon is desirable, especially in the new millennium of global trade, multi-cultural societies, and the Internet. However, equally, in an era when many are prone to draw superficial comparisons between policies and practices adopted in different countries, we argue the need for caution (Walker & Dimmock, 2000a). In particular, such comparisons, we claim, can be fatuous and misleading without thorough understanding of the contexts, histories, and cultures within which they have developed. Our main purposes in this chapter are thus twofold. First, to argue the need to develop a comparative and international branch of educational leadership and management. Second, to propose a comparative model of educational leadership and management based on cultural and cross-cultural analysis. The chapter begins with the justification for developing a comparative branch of the field. It then goes on to explain the appropriateness of culture as a core concept in developing comparative educational management. A model is then proposed as a useful conceptual framework for drawing valid international comparisons in school leadership and management. Finally, we allude to some challenges and limitations of the approach.

Justification for Comparative and International Educational Leadership and Management

Growing awareness of and interest in the phenomenon of globalization of educational policy and practice is creating the need for the development of a comparative and international branch of educational leadership and management (Dimmock & Walker 1998a, 1998b). Interest in, if not willingness to adopt, imported policies and practices without due consideration of cultural and contextual appropriateness is justification for developing a more robust conceptual, methodological, and analytical approach to comparative and inter-national educational management. Currently, educational management has failed to develop in this direction. Indeed, as we argue below, it shows every tendency to continue its narrow ethnocentric focus, despite the internationalizing of perspectives taken by policy makers and others to which we have already alluded. In this respect, it could be argued that our field is lagging behind conceptually and epistemologically trends and events already taking place in practice. In addition, it has already failed to keep pace with comparative and international developments in other fields, notably business management and cross-cultural psychology.

Globalization of policy and practice in education is in part a response to common problems faced by many of the world’s societies and education systems. Economic growth and development are increasingly seen within the context of a global market place. Economic competitiveness is seen to be dependent on education systems supplying sufficient flexible, skilled “knowledge workers.” This phenomenon, however, emphasizes the need to understand the similarities and differences between societies and their education systems. No two societies are exactly alike demographically, economically, socially, or politically. Thus an attraction of an international and comparative branch to educational management is systematic and informed study leading to better understanding of one’s own as well as others’ education problems and their most appropriate solutions.

A strong argument for the need to develop an international and comparative branch to the field is the ethnocentricity underlying theory development, empirical research, and prescriptive argument. Anglo-American scholars continue to exert a disproportionate influence on theory, policy, and practice. Thus, a relatively small number of scholars and policy makers representing less than eight percent of the world’s population purport to speak for the rest. Educational management has a vulnerable knowledge base. Theory is generally tentative and needs to be heavily qualified, and much that is written in the field is prescriptive, being reliant on personal judgement and subjective opinion. Empirical studies are rarely cumulative, making it difficult to build systematic bodies of knowledge. Yet despite these serious limitations, rarely do scholars explicitly bound their findings within geocultural limits. Claims to knowledge are made on the basis of limited samples as though they have universal application. A convincing case can be mounted for developing middle range theory applying to and differentiating between different geocultural areas or regions. During the next decade there is need to develop contextually bounded school leadership and management theories. This will allow us to distinguish, for example, how Chinese school leadership and management differs from, say, American or British.

A further concern leading to the need for a distinctive branch of comparative educational management is the need for more precise and discriminating use of language. Many writers, for example, glibly use terms such as “Western, ” “Eastern, ” or “Asian” in drawing comparisons. Little attempt is made, however, to define or distinguish these collective labels, a serious omission when there is likely to be as much variation within each of them as between them. For example, major contextual and cultural differences apply between English-speaking Western countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States, let alone between the United Kingdom, United States, France, and Germany, with their different languages and locations on two continents. Yet they are all examples of so-called ‘Western countries. Likewise, when referring to the ‘East’ or to ‘Asia,” major cultural differences are to be found between China, Japan, Korea, Malaysia and Singapore. Developing comparative educational management might introduce more rigor and precision in the terms used to define education systems geographically and culturally.

Why Cultural and Cross-Cultural Analysis as the Basis of Comparison?

In building a comparative and international branch of educational management, it is necessary to make a convincing case for an appropriate theoretical or conceptual foundation. For this we have turned to the notion of culture, and societal culture in particular. An increasing recognition of the importance of societal culture and its role in understanding life in schools is very recent. “Culture” is defined as the enduring sets of beliefs, values, and ideologies underpinning structures, processes, and practices that distinguishes one group of people from another. The group of people may be at school level (organizational culture) or at national level (societal culture).

Both Cheng (1995) and Hallinger and Leithwood (1996a) have argued for greater cognizance to be taken of societal culture in studies of educational leadership and educational administration. Our case for developing a cultural and cross-cultural approach rests on at least three reasons: first, the suitability of culture as a base concept for comparative study; second, the limitations of existing models and concepts used in comparative study; and third, the consequences of continuing to ignore culture as an influence on practice and understanding in educational leadership and management (Walker & Dimmock, 1999). Each of these reasons is examined in turn.

The Suitability of Culture

Culture at the organizational level is now a well-recognized and increasingly studied concept in school leadership and management (Bolman & Deal, 1992; Duke, 1996). Culture at the societal level, however, has not received similar attention. Since culture is reflected in all aspects of school life, and people, organizations, and societies share differences and similarities in terms of their cultures, it appears a particularly useful concept with universal application, one appropriate for comparing influences and practices endemic to educational leadership and management.

Since culture exists at multiple levels (school and sub-school, local, regional, and societal), it provides researchers with rich opportunities for exploring their interrelationships, such as between schools and their micro- and macro-environments. It also helps identify characteristics across organizations that have surface similarity but are quite different in modus operandi. For example, schools across different societies look to have similar, formal leadership hierarchies, but these often disguise subtle differences in values, relationships, and processes below the surface.

Most cross-national studies of educational leadership have ignored the analytical properties of culture. Such neglect has been challenged recently by researchers such as Cheng (1995), who assert that, “the cultural element is not only necessary, but essential in the study of educational administration” (p. 99). Specifically, Cheng bemoans the fact that much research in educational administration ignores culture and makes no reference to larger macro-societal or national cultural configurations. The concept of national culture has not been rigorously applied as a basis for comparison in educational leadership or as a means for comparing the organization of individual schools. Neither has culture at the organizational level been developed as a foundation for comparative analysis; rather, it has been applied to areas such as school effectiveness and organizational analysis.

Limitations of Existing Comparative Approaches

A second argument for a cross-cultural approach to comparative educational leadership and management is that existing comparative education frame-works tend to focus on single levels and to assume structural-functionalist approaches. Single-level frameworks ignore the relationships and interplay between different levels of culture, from school to societal, thereby failing to account sufficiently for context. For example, Bray and Thomas (1995) claim that national or macro-comparative studies tend to suffer from overgeneralization, and therefore neglect local differences and disparities. Likewise, within-school studies tend to neglect the external school context.

In unraveling the dynamic, informal processes of schools and the leadership practices embedded within them, theoretical tools that stretch beyond structural-functionalist perspectives should be considered. Although structural-functionalist models are useful for fracturing education systems into their constituent elements (structures), their explanatory potential is limited as to how processes, or why various elements, interact. As a result, their analytic power is diminished through adopting static rather than dynamic views of schools. Consequently, explanation remains at a surface level, and rigorous comparison remains rare. We suggest that multilevel cultural perspectives need to be taken in aiding analysis and understanding of schools and their leaders.

Cultural Borrowing of Educational Policies and Practices

Our third justification for adopting a cross-cultural approach to comparative educational management relates to the globalization of policy and practice (Dimmock, 1998; Hallinger & Leithwood, 1996b; Walker & Dimmock, 2000b). Policy makers and practitioners are increasingly adopting policy blue-prints, management structures, leadership practices and professional development programs fashioned in different cultural settings while giving little consideration to their cultural fit. In seeking to understand why some leadership practices appear to be workable in some contexts but not others, and the nature of adaptation needed, there is a clear need to take the cultural and cross-cultural contexts into account.

The dominance of Anglo-American theory, policy, and practice denies or understates the influence that culture, and societal culture in particular, may have on the successful implementation of policy. There is serious risk at present that our understandings will remain too narrowly conceived. A comparative approach to educational leadership and management can expose the value of theory and practice from different cultural perspectives, which may then, in turn, inform and influence existing dominant Western paradigms.

A Model for Cross-Cultural Comparison in Educational Leadership and Management

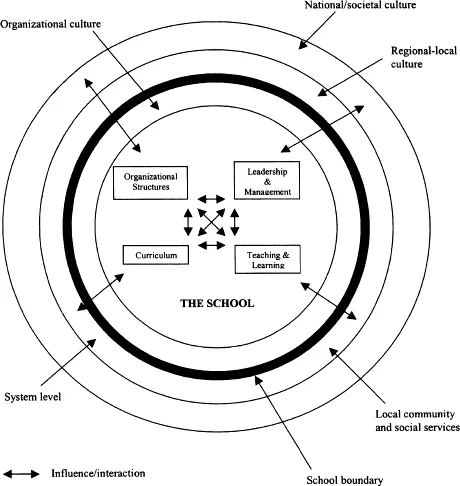

An overview of our cross-cultural comparative model is provided in Figure 1.1. The model is comprised of two interrelated parts:

- a description of the four elements constituting schooling and school-based management (see Figure 1.2 for a breakdown), and

- a set of six cultural dimensions at each of the societal and organizational levels that provide common scales for comparison (see Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.1 A cross-cultural school-focused model for comparative educational leadership and management.

Figure 1.1 illustrates the four elements of schools and the two sets of cultural dimensions—societal and organizational. Comparative analysis is aimed at the relationship between the two levels of culture and the four elements constituting the school. In Figure 1.1, organizational culture is conceptualized as internal to the school but bounding the four elements, reflecting its capacity as both a dependent and independent variable with regard to the four elements of the school and schooling. National or societal culture, however, is depicted as circumscribing the school but at the same time, spanning the school boundary to interact with organizational culture and to affect the four elements of the school.

The school is taken as the unit of analysis for comparison in our frame-work and is assumed to comprise four elements: organizational structures; leadership and managerial processes; the curriculum, which is a school sub-structure; and teaching and learning, which is a sub-set of school processes (Figure 1.1). These four elements provide a convenient way of encapsulating the main structures and processes that constitute the schooling and school-based management. Two of the four comprise the managerial and organizational aspects of school life, while the remaining two elements form the core technology of the school concerned with curriculum, teaching, and learning. Elsewhere (Dimmock & Walker, 1998b), we have explained the four elements in full and the interrelationships between them. Relationships with other parts of the system, such as the district and central office, and with local community and social service agencies are also considered (see Figure 1.1). Below we provide a brief overview of all four.

The Four Elements of Schooling and School-Based Management

Organizational Structures

“Organizational structures” refer to the more or less enduring configurations by which human, physical and financial resources are established and deployed in schools. Structures represent the fabric or framework of the organization and are thus closely associated with resources and their embodiment in organizational forms. They also provide policy contexts within which schools have greater or lesser discretion. Thus, schools in strongly centralized systems experience more explicit and rigid po...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Series Preface

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction

- Part I: Conceptualizing and Researching the Influence of Societal Culture

- Part II: The Influence o f Societal Culture on Schools and School Leadership

- Index