- 372 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this fully revised and updated edition of his groundbreaking study, Paul Cartledge uncovers the realities behind the potent myth of Sparta.

The book explores both the city-state of Sparta and the territory of Lakonia which it unified and exploited. Combining the more traditional written sources with archaeological and environmental perspectives, its coverage extends from the apogee of Mycenaean culture, to Sparta's crucial defeat at the battle of Mantinea in 362 BC.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sparta and Lakonia by Paul Cartledge in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I |

Introduction

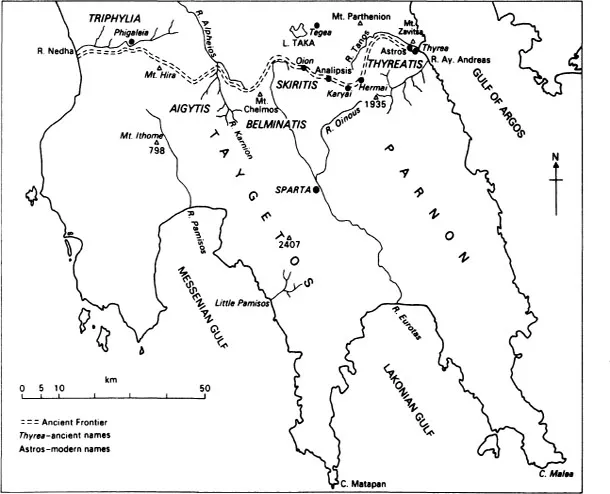

Figure 1 The frontiers of Sparta c. 545

Chapter one

Boundaries

‘Without a geographical basis the people, the makers of history, seem to be walking on air.’ So wrote Jules Michelet in the 1869 Preface to his celebrated Histoire de France – but in vain, it seems, so far as most historians of Sparta have been concerned. For it remains as true of them today as it was of historians in general in the nineteenth century that, once the de rigueur introductory sketch of geographical conditions is out of the way, the substantive analysis or narrative proceeds ‘as if these complex influences ... had never varied in power or method during the course of a people’s history’ (Febvre 1925, 12).

There is, however, perhaps even less excuse for this outmoded and harmful attitude in studying classical Sparta than in studying some other ancient Greek states. For, as is well known, the Spartans throughout the period of their greatest territorial expansion and political supremacy (c. 550–370) rested their power and prosperity on the necessarily broad backs of the Helots, the unfree agricultural labourers who lived concentrated in the relatively fertile riverine valleys of the Eurotas in Lakonia and the Pamisos in Messenia. And besides the Helots there literally ‘dwelt round about’ the Perioikoi, who were free men living in partially autonomous communities and providing certain essential services for the Spartans but farming more marginal land. Any serious account of Spartan history therefore is obliged to make more than a token gesture at understanding the mutual relationships of these three groups of population. Thus it is with the ‘infrastructure of land allotments, helots and perioeci, with everything that includes with respect to labour, production and circulation’ (Finley 1975, 162) that this study will be primarily concerned, in a determined effort to bring the Spartans firmly down to earth.

In this connection it is encouraging to note the recent upturn of interest in a more broadly geographical and materialist approach to Graeco-Roman antiquity – not to mention prehistoric Mediterranean studies, where, as we shall see in more detail in Chapters 4 and 6, the lack of written texts necessitates an overriding concern with the total recoverable human and natural environment. A leading exponent of Roman agrarian history has recently defined a major desideratum as ‘close study, region by region, of the changing patterns of land use and agricultural production, supported by analysis of demographic and other socio-economic data provided by our sources’ (White 1967, 78). This applies equally to Greece. Moreover, not only does he state the objective clearly, but he conveys too the limitation imposed by the available evidence.

However, before the nature, extent and quality of the evidence can be explored, a prior question obtrudes itself. What is a ‘region’? The answer is not as straightforward as might at first blush be supposed, for it implies a solution to the notorious problem of frontiers or boundaries. ‘Natural’ frontiers may have been consigned for good to the conceptual rubbish-heap, but should they be replaced by a strictly geographical, a vaguely cultural or a broadly political notion of regional demarcation? I have little doubt that for the geographically minded historian like myself, as opposed to the historical geographer, the third course is the one to be adopted. To quote Lucien Febvre (1925, 311) once more, ‘all States consist of an amalgam of fragments, a collection of morsels detached from different natural regions, which complement one another and become cemented together, and make of their associated diversities a genuine unity.’ Our task therefore will be to explain how the frontiers of Lakonia came to be fixed where they were and why from time to time they fluctuated.

There have been many Lakonias. That is to say, ‘Lakonia’ has experienced many incarnations and metamorphoses between the earliest use of the name (in late Roman or early mediaeval times) and its present application to one of the provinces of contemporary Greece. The Lakonia of my title, however, is none of these. Indeed, the name is convenient and useful precisely because it has no exact political denotation for the period chiefly under consideration in this book, c. 1300 to 362. It should serve therefore as a constant reminder that the size of Lakonia in antiquity varied directly in proportion to the strength and inclinations of the inhabitants of its central place, which from about 1500 has been located in the vicinity of modern Sparta.

Frontiers should not of course be viewed as it were from the outside; but if ‘Lakonia’ is to be used for purposes of description and analysis, it requires spatial definition. It has seemed most convenient, and on balance historically least misleading, to fix upon the status quo of c. 545, a high-water mark from which the Spartan tide was not compelled to recede for almost two centuries. Hence my Lakonia, like the ancient terms ‘Lakedaimon’ and ‘Lakonike’ (sc. ge), will also encompass south-west Peloponnese, which will be referred to hereafter for convenience as Messenia. I shall not, however, use ‘Lakonia’ to obliterate the separate identity of Messenia in the way that ‘Lakedaimon’ and ‘Lakonike’ designedly did. For I shall be principally concerned with Lakonia in a narrower and more familiar sense, roughly the territory east of the Taygetos mountain range (but including the whole of the Mani). This is primarily because this smaller Lakonia was the heartland and laboratory in which the Spartans first experimented with the system whose essentials they later transferred to Messenia, but also because the evidence for Messenia has recently been collected, sifted and published (admittedly with a primary emphasis on the Late Bronze Age) in exemplary fashion by the University of Minnesota Messenia Expedition (MME; cf. now Meyer 1978).

Our sources for the frontier consist of scattered notices in ancient authors, especially Strabo and Pausanias, and those physiographical features that have undergone no – or no significant – alteration since our period. (Epigraphical evidence, apart from some dubious cuttings in the living rock at Arkadian Kryavrysi, is confined to the western frontier of the reduced Lakonia after the liberation of Messenia from the Spartan yoke in c. 370: Chapter 15.) Needless to say, no ancient literary source made a consistent effort to define the extent of territory under Spartan control at any given point in history, so all due credit should go to Friedrich Bölte, the first scholar to appreciate and exploit the potential of clear and detailed geological maps (Bölte 1929, 1303–15).

On the east, south and west Lakonia is bounded by the Mediterranean. Only in the north are the geographical limits blurred, and even here the lack of clarity is merely in detail, for the main outline can be simply described. Once the Thyreatis (ancient Kynouria) had fallen permanently to Sparta as the prize for winning the ‘Battle of the Champions’ in c. 545, the frontier ran from a point on the east coast some two kilometres north of modern Astros (near ancient Thyrea) along a range of hills above the River Tanos east of Mount Parthenion (1,093 m.). Westwards the border was formed by the watershed of the Eurotas and the tributaries of the east Arkadian plain. To the west of the Taygetos range the northern frontier of Messenia skirts the southern edge of the plain of Megalopolis. West of the latter it loops round the ancient Mount Hira (864 m.) to run out into the sea along the Nedha valley, the southern boundary of the transitional region of Triphylia.

The details are more complex, but the Thyreatis at least poses few problems. It is bounded on the north by Mount Zavitsa, on the west by the Parnon mountain range and in the south by the river of Ay. Andreas. In the mid-second century AD the frontiers of the Spartans, Argives and Tegeans met on the ridges of Parnon (Paus. 2.38.7). Thus if the Hermai have been correctly identified at modern Phonemenoi (Rhomaios 1905, 137f.; 1951, 235f.), the frontier will have made the expected abrupt turn south of Mount Parthenion and followed Parnon in a southerly direction for about ten kilometres.

Our next evidence consists in the identification of Perioikic Karyai, which lay on the ancient frontier. It almost certainly occupied the vicinity of modern Arachova (now renamed Karyai) a short way south-east of Analipsis, which remains a border-village to this day (Loring 1895, 54–8, 61; Rhomaios 1960, 376–8, 394). The statement of Pausanias (8.54.1) that the River Alpheios marked the border between Spartan and Tegeate territory has caused difficulties, perhaps to be resolved by identifying Pausanias’ Alpheios with the river of Analipsis, the uppermost course of the Sarandapotamos, which either did, or was believed to, form part of the great Alpheios (Wade-Gery 1966, 297f., 302).

Our next clue is the frequent mention in the sources of the sub-region of Skiritis, whose control was vital to Sparta since it lay athwart routes from Arkadia to Lakonia and Messenia. Bölte identified Skiritis with the crystalline schist zone between the River Kelephina (ancient Oinous) and the Eurotas to west of the ‘saddle’ of Lakonia. This is in harmony with the fact that the only ancient settlement in Skiritis accorded independent mention in the sources is Oion, a frontier-village and guardpost which was probably situated in a small ruined tract north of modern Arvanito-Kerasia (Andrewes in Gomme 1970, 33). In other words, at Analipsis the ancient frontier deviated sharply from its modern counterpart and moved north-west to make considerable inroads into the present-day province of Arkadia.

West of the headwaters of the Eurotas Mount Chelmos rises to 776 m. above sea-level. The region at its foot has been securely identified with ancient Belmina or Belminatis (other variant spellings are found). This was a frontier-zone hotly disputed between Sparta and Megalopolis after the foundation of the latter in 368 (Chapter 13) as much for its abundant water-supply as for its strategic position (Howell 1970, 101, no. 53). In the extreme north-west angle of Lakonia lay Aigytis, a large trough drained to the northwest by the River Xerillos (ancient Karnion). Entering Messenia Mount Hira, like Andania further south (MME 94, no. 607?), is perhaps best known for its role in the final stage of the Spartan conquest in the seventh century. Further expansion to the north was barred at this point by Phigaleia, but neither Phigaleia nor Elis was able to prevent Sparta from exercising a fitful de facto control over Triphylia, perhaps from as early as the late eighth century. Messenia proper, however, was bounded on the north by the Nedha valley, a ‘natural no-man’s land’ (Chadwick 1976a, 39).

Such was the area available to the Spartans from c.545, some ‘two-fifths of the Peloponnese’ according to an ancient estimate (Thuc. 1.10.2) or about 8,500 km2. No other polis (city-state) could compete; Athens, for example, Sparta’s nearest rival, commanded only about 2,500. Mere size, however, does not by itself account for the power and influence wielded by Sparta for so long a period. The question which the present work will attempt to answer is how, and in particular how efficiently, did Sparta utilize the possibilities afforded by this (in Greek terms) enormous land-mass.

We must conclude this first introductory chapter by looking at a second, and in some ways the most important, boundary, the one fixed by the available source-material. Greek geography, broadly interpreted, developed alongside history as a branch of Ionian ‘historie’ (enquiry) in the sixth and fifth centuries. But whereas history (in something like the modern sense) was an invention of the fifth century (Chapter 5), ‘scientific’ geography was a Hellenistic creation. At the threshold of the latter epoch stood Theophrastos, the most distinguished pupil and successor of Aristotle at the Lyceum, to whom we owe the first fumblings towards a systematic botany and geology. Theophrastos by himself, however, despite his frequent references to Lakonia, is totally inadequate for our purposes and must be supplemented by ancient literary evidence of the most disparate origins and of correspondingly disparate value. We have already met Thucydides, Strabo and Pausanias: in what follows I shall have occasion to draw on – among many others – Alkman, Herodotus, Aristophanes, Plato, Vitruvius and Athenaios. By no means all of these inform us directly of conditions in Lakonia, or even of conditions in our special period; many have no interest in the information for its own sake; all too often they convey only the extremes experienced, precisely because they were extreme.

There are, though, two main types of evidence by which the unsatisfactory literary sources can be complemented or corrected, archaeology and modern scientific data relating to all aspects of the environment. Controlled excavation in Lakonia has for a variety of reasons been lamentably slight, a deficiency that for many historical purposes is irremediable. There are, however, other methods of building up the archaeological record besides excavation, and in the following chapters I shall be discussing, and utilizing the results of, all available archaeological techniques. Here, however, I propose to examine briefly what I take to be the inherent limitations of archaeological material as historical evidence, regardless of the quantity or quality of the available data (ideally of course data susceptible of statistical analysis). For even though the spade may be congenitally truthful, ‘it owes this merit at least in part to the fact that it cannot speak’ (Grierson 1959, 129). Material remains, in other words, may be authentic testimony to the times they represent, but they are not self-explanatory, and a long-standing dispute concerns itself with the problem of precisely what kinds of inference it is possible or legitimate to draw from them. This dispute has of late received a fresh injection of vitality from the so-called ‘new’ archaeologists, who (in the words of a leading spokesman) advocate a ‘shift to a rigorous hypothetico-deductive method with the goal of explanation’ and believe ‘there is every reason to expect that the empirical properties of artifacts and their arrangement in the archaeological record will exhibit attributes which can inform on different phases of the artifact’s life-history’ (Binford 1972, 96, 94).

Now while I agree wholeheartedly with the stated aim of the ‘new’ archaeologists of explaining whole societies in systematic terms, I have to confess my profound disagreement on two counts. First, I do not believe that our categories of social analysis are yet sufficiently fine to be capable of expression in the form of laws from which deductions may automatically be made. Symptomatically, the ‘new’ archaeologists have been surprisingly happy to operate with models which resemble ‘parables’ and betoken ‘creeping crypto-totalitarianism’ (Andreski 1972, ch. 13). Second, I remain firmly within the camp of such ‘old’ archaeologists as Piggott (1959, ch. 1) on the question of what kinds of inference one may legitimately draw from the accidentally surviving durable remains of complex social arrangements. I believe, in short, that there is a hierarchy or pyramid of levels at which material data may be explained in economic, political and social terms. From archaeological evidence alone we may infer (relatively) much about material techniques, a considerable amount about patterns of subsistence and utilization of the environment, far less about social and political events and institutions, and least of all about mental structures, religious and other ‘spiritual’ ideas and beliefs. To take a simple example, the fact that the art of Sparta’s colony Taras was largely in the Spartan tradition does not by itself show that political relations with the mother-city were cordial: the art of Kerkyra was wholly in the Corinthian tradition, and yet we know from literary sources of political friction, even outright warfare, between Kerkyra and Corinth from an early date (Boardman 1973, 219). This is not of course to deny that technique and subsistence-patterns may themselves imply non-material features of social existence. It is to deny that there are assured criteria whereby one may automatically infer the latter from the former. For ‘there is sufficient evidence that identical artifacts and arrangements of artifacts can result from different socio-economic arrangements of procurement, manufacture or distribution’ (Finley 1975, 90).

On the other hand, the ‘new’ archaeologists – apart from those who adopt a non-historical or anti-historical approach – have performed a signal service in asking questions which ‘old’ archaeologists, especially perhaps those whose business is with the classical Graeco-Roman world, had considered either outside their province or not worth asking. To this extent ‘social archaeology’ (Renfrew 1973) represents a major step in the right direction, and it is to be hoped that the questions, techniques and methods it employs (minus the inappropriate ‘systems’ models) will consistently be directed to the material remains of Graeco-Roman antiquity both in their excavation and in their interpretation.

The rest of this chapter will consider how far the historian of ancient Lakonia can use modern scientific data to eke out, modify or explain the notoriously unstatistical ancient sources. Here we are brought hard up against the recalcitrant problem of climatic change. For, since climate influences human social behaviour primarily through the medium of the plant, and since we are relatively well informed on the agricultural potentialities of contemporary Lakonia, it is essential to assess first how far the climate in our period resembled that known to have prevailed in the last century or so and then whether it had remained more or less constant in the interim.

Climate itself, however, is a complex concept. Its basic conditions have been elucidated as follows (Lamb 1974, 197): the radiation balance; the heat and moisture brought and carried away by the winds and ocean currents; the local conditions of aspect towards the midday sun and prevailing winds;the thermal characteristics of the soil and vegetation cover; and the reflectivity of the surface. Human influence on climate, though by no means negligible, is problematic (Mason 1977). Thus the reconstruction of past climate involves a variety of techniques, mainly scientific. Progress in their application has brought the realization that a rigorous distinction must be drawn between climatic fluctuations or oscillations, which are regular and occur in cycles ranging from decades to centuries (intervals of 200 and 400 years appear to be quite prominent), and climatic changes, which are relatively infrequent.

However, it is also clear from the extent of disagreement among experts that there is, in the first place, room for more than reasonable doubt as to which of the basic conditions of climate are decisive for climati...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of figures

- Preface

- Preface to the second edition

- Notes on the spelling of Greek words and on dates

- Part I Introduction

- Part II Preclassical Lakonia c.1300–500BC

- Part III Classical Lakonia C.500–362BC

- Part IV Results and prospects

- Appendix 1 Gazetteer of sites in Lakonia and Messenia

- Appendix 2 The Homeric poems as history

- Appendix 3 The Spartan king-lists

- Appendix 4 The Helots: some ancient sources in translation

- Appendix 5 The sanctuary of (Artemis) Orthia

- Abbreviations

- Bibliographical appendix to the second edition

- Bibliographical addenda to the second edition

- Bibliography

- Index