- 500 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Construction Safety Management Systems

About this book

The construction industry has a distressingly poor safety record, whether measured in absolute terms or alongside other industries. The level of construction safety in a country is influenced by factors such as variations in the labour forces, shifting economies, insurance rates, legal ramifications and the stage of technological development. Yet the problem is a world-wide one, and many of the ways of tackling it can be applied across countries. Effective tools include designing, preplanning, training, management commitment and the development of a safety culture. The introduction and operation of effective safety management systems represents a viable way forwards, but these systems are all too rarely implemented. How can this be done? Should we go back to prescriptive legislation? This book considers these questions by drawing together leading-edge research papers from the proceedings of an international conference conducted by a commission (W099) on Safety and Health on Construction Sites of CIB, the international council of building research organisations.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1: Overview of Construction Site Safety Issues

Steve Rowlinson

INTRODUCTION

The aim of this chapter is to introduce the construction industry, its safety and health issues and to discuss the nature of the industry by way of background and to highlight how it differs from other industries as the construction industry is rather different from the majority of industries and has its own organisational and economic characteristics. This chapter will focus on the particular nature of management and organisation in the construction industry and introduce the nature of the work undertaken and the persons employed in industry. It draws on the work presented by the various authors and the research of the editor.

Beyond this basic introduction, the chapter lays out the structure of this book and identifies the book's six main themes, namely: international comparisons as a scene setter; safety management issues and the implementation of these systems; health issues and their importance (and relative neglect to date); the role of training and education in underpinning safety management systems; safety technology and its role vis a vis safety management systems; and accident analysis as a means of improving performance and providing feedback to the safety management system. Some basic statistics are presented and the key issues of prescriptive versus performance based safety and health legislation and the unique nature of the construction industry are discussed.

Despite the attention given to construction sites injuries in many countries, the statistics continue to be alarming. For instance, fatal accidental injury rates in the United Kingdom and Japan are reported to be four times higher in the construction industry.

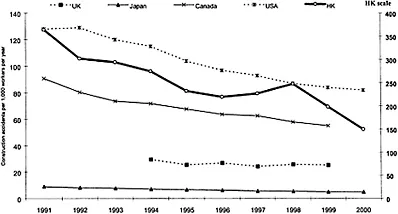

When compared to the manufacturing industry (Bentil, 1990). Construction is often classified as a high-risk industry because it has historically been plagued with much higher and unacceptable injury rates when compared to other industries. In the United States, the incidence rate of accidents in the construction industry is reported to be twice that of the industrial average. According to the National Safety Council, there are an estimated 2,200 deaths and 220,000 disabling injuries each year (NSC, 1987). The extent of the problem in selected countries worldwide is indicated in Figures 1.1 and 1.2 below.

Hinze discusses what it is that makes construction work dangerous and he disagrees with the notion that construction work is inherently dangerous and injuries are more likely to occur in this industry as he believe such a fatalistic view is inappropriate to construction safety then it is possible to improve the safety record of the industry.

Figure 1.1 Accidents per 1,000 Construction Workers per year

(Sources: Japan Statistical Yearbook, Ministry of Public Management, Home Affairs, Posts and Telcommunications; Japan International Center for Occupational Safety and Health (JICOSH); Fatal Injuries to Civilian Workers in the United States, 1980–1995; United States Bureau of Labor Statistics Data, U.S. Department of Labor; Health and Safety Statistics, HSE publication; ILO Yearbook of Labour Statistics 2001, International Labour Office, Geneva; Occupational Safety & Health Branch of the Labour Department, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.)

. Rather, Hinze indicates that if a proactive is taken

Figure 1.2 Fatal Accidents per 100,000 Construction Workers per year (Sources: as above)

He goes on to argue that although it has been possible to reduce accident rates in the United States by a considerable margin he believes there is still much room for improvement (Hinze, 1997:5–7).

It is obvious from the figures shown here that construction is an industry with a poor safety record worldwide. However, it is possible to improve this safety record by taking due credence of and paying appropriate attention to a series of operations and management systems that can be implemented. These systems are applicable worldwide but must be applied within the cultural context of each country, and indeed construction site, if they are to be fully effective. Later in this book it will be argued that many safety initiatives cannot be wholly successful without a high degree of top-level management commitment and without an appropriate safety infrastructure being in place.

The issue of construction site safety has engaged both practitioners and researchers for a long time. Hinze (1981) investigated the relationship between the safety performance of individual workers and individual worker attitudes. Hinze and Raboud (1988) explored several factors that apparently influence safety performance on Canadian high-rise building projects. In some studies, the usefulness of behavioral techniques to improve safety performance in the difficult construction setting was examined. The study by Mattila and Hyodynmaa (1988) revealed that when goals were posted and feedback was given, the safety index was significantly higher than when no feedback was given. Fellner and Sulzer-Azaroff (1984) analysed the industrial safety practices through posted feedback. In a study carried out on Honduras construction sites, Jaselskis and Suazo (1994) demonstrated a substantial lack of awareness or importance for safety at all levels of the construction industry. In addition, Laufer and Ledbetter (1986) assessed various safety measures. Other researchers examined costs of construction accidents to employers (Leopold and Leonard, 1987, Levitt and Samelson, 1993). With regards to construction site safety in Hong Kong, Lingard and Rowlinson (1994) investigated the theoretical background to commitment at the group and organisational level and presented a site-level research model which is illustrative of the possible effects that these have on performance. A more recent study by Tam, Fung and Chan (2001) explored the attitude change in people after the implementation of the new safety management system in Hong Kong.

It has been argued that the construction industry is essentially very different from manufacturing industries and so it is impossible for the techniques and systems used in those industries to be effective in the construction industry. The argument has some weight and will be further discussed in this book. However, this argument does not lead to the conclusion that construction works cannot be made safe. This would be an inappropriate conclusion but, for such improvements to be made, it would be necessary to adopt innovative and specifically focused measures for the construction industry. The following section will discuss the nature of construction works in order that the problem of construction site safety can be addressed in an appropriate context.

1.1 INTRODUCTION TO CONSTRUCTION SITE ORGANISATION

1.1.1 Civil and building works

Construction works have traditionally been divided into two distinct types: civil engineering works and building works. The former includes construction of roads, bridges, dams and the like and these are in most instances horizontal construction projects. They involve the use of large items of plant and equipment. Building works tend to focus upon vertical construction, such as offices, apartments, factories and involve mainly production of facilities in which people or equipment will be housed. Building works tend to be less plant intensive and more labour intensive than civil engineering works, in general. As a consequence, both types of construction work face particular problems that are peculiar to the building or civil engineering sectors. However, some of the problems faced are much more generic in nature and apply to both types of construction. Maintenance works form a significant part of the construction industry workload and contribute significantly to accident rates. The breakdown of work between building and civil engineering construction is roughly similar worldwide but that for each country the exact breakdown varies from year to year. During periods of development a country will normally have a higher percentage of civil works. Specific figures are not included in this book but it is generally held that civil engineering works are somewhat safer than building works. That does not mean that the accident record for civil engineering works is acceptable but it is purely a reflection of the nature of the works being undertaken.

1.1.2 Subcontracting systems

Most works undertaken in either building or civil engineering are undertaken on a subcontract basis. The building industry probably uses rather more subcontracting than does the civil engineering industry. Subcontracting is the system by which work is allocated to a main contractor that does not construct the works itself but employs subcontract organisations to produce the finished product. Typical subcontracting firms would specialise in areas such as concreting works, bricklaying, falsework and formwork erection and foundation construction. The organisation actually undertaking the construction works is rather small compared with the total size of the project. Herein lies one of the problems that besets the construction industry. When the size of the organisation undertaking construction work falls below a critical mass then the resources and facilities to enable safe construction are not readily available. This is a structural problem that occurs in most national construction industries and poses management difficulties in terms of construction site safety, productivity and quality management. Small firms, as are many subcontractors, are unable to adequately train and educate workers and this phenomenon has led to a problem of reduction in apprenticeships which has led to a shortage of skilled, trained labour. This leads to the consequence of poor performance in terms of productivity and quality and, inevitably, site safety. This is not an issue that can be dealt with by individual companies on their own very readily. If one company takes the lead in moving towards directly employed labour it is likely this company will be undercut by competitors making use of subcontractors. However, it is possible to address this issue through concepts such as partnering and this particular solution is discussed later in the book.

1.1.3 Construction contracting

Most construction contracts are awarded through competitive tenders, with the lowest bidder taking the contract. This system has been identified as the cause of a vicious circle of cost cutting and claims generation. This has impacted on project performance in terms of time, cost and quality but it also has an effect on safety. The first item that suffers in the competitive bidding system is often the safety budget. However, it is unlikely that the competitive tendering system will be quickly abandoned in the construction industry. Although concepts such as partnering have taken a strong hold in many industries, they still do not account for a large proportion of the construction works being undertaken. As a consequence, it is necessary to look at the nature of the construction contracting company and how these companies organise their construction sites.

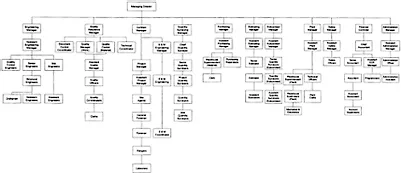

Most construction companies operate with an organisation structure similar to that shown in Figure 1.3. In such a company the head office functions and the site functions operate fairly independently. As a consequence there is a great deal of decentralisation and much decision-making is made at the construction site level. Hence, in terms of safety there is an issue here. No matter how well organised the head office safety management system might be this system has to be implemented at the site level by independent groups or teams. The construction site team is normally headed by a project manager or site agent and this person is normally assisted by professionals such as engineers and quantity surveyors. However, the majority of the construction work is, of course, undertaken by construction workers who are supervised by foremen and gangers. These are the people who have most contact with the workers: the workers are of course those who are at most risk. Hence, the chain of command and the ability to influence workers is exceptionally long and the trail back to the head office is unlikely to be an easy one to follow. Hence, in a rather different manner to a factory, most people on the construction site operate autonomously and vigilance and monitoring is vitally important.

It is important to realise that the construction site is a highly autonomous organisation. As such it is very difficult for the head office to control what goes on the site on a day-today basis. In fact, on large construction sites, it is often difficult for the site agent to control what goes on a day-to-day or even hour-to-hour basis. Consequently, construction workers are expected to operate with a high degree of independence and initiative. In such situations, the non-standard work procedures are often undertaken. Thus, the potential for accidents and mishaps is large and this is undoubtedly a characteristic of the industry as it operates today. Given this very different type of organisation it is important that specific, tailored safety and health programmes are prepared for the construction industry. It is not possible to transplant systems that work in factories and offices on to the construction site.

Figure 1.3 Typical organization structure of a construction company

1.1.4 Temporary multi-organisations

Construction project teams are generally temporary multi-organisations. By this it is meant that a group of organisations come together to form a project team, more correctly described as a coalition, for the purpose of the completion of the construction project. This team employs both design professionals and construction professionals, as well as financial controllers such as quantity surveyors. The nature of this temporary multi-organisation, TMO, is well described in the paper by Cherns and Bryant, 1984. The significance of the TMO is that it is an organisation that has no long track record of working harmoniously together. Hence, every time a team is set-up a new series of relationships, procedures and methods have to be established. The different organisations have to be integrated and the ways of operating have to be adjusted in order that they can work effectively together. This process takes time and, sometimes, is impossible to achieve due to structural or attitudinal problems within organisations or members of organisations. Hence, the industry is highly differentiated in terms of organisation and requires a high level of integration to ensure that all operational systems, including safety management systems, are implemented effectively.

1.1.5 Organic organisations

The construction project team could be described as an organic organisation. Organic organisations tend to have no firmly set procedures or rules of conduct laid down and are organisations which can react rapidly to changes in the environment. This is important in the construction industry where often it is not possible to plan more than a few days ahead due to changing circumstances, design changes and weather disturbances. As a consequence the organisation needs a great deal of integrative and co-ordinative effort in order to function properly. Mechanistic organisations, the oppo...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Overview of Construction Site Safety Issues

- Section 1: International Comparisons

- Section 2: Safety Management Issues

- Section 3: Health Issues

- Section 4: Training and Education

- Section 5: Safety Technology

- Section 6: Accident Analysis

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Construction Safety Management Systems by Steve Rowlinson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.