- 407 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The earliest sites at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania are among the best documented and most important for studies of human evolution. This book investigates the behavior of hominids at Olduvai using data of stone tools and animal bones, as well as the results of work in taphonomy (how animals become fossils), the behavior of mammals, and a wide range of ecological theory and data. By illustrating the ways in which modern and prehistoric evidence is used in making interpretations, the author guides the reader through the geological, ecological, and archeological areas involved in the study of humans.Based on his study of the Olduvai excavations, animal life, and stone tools, the author carefully examines conventional views and proposals about the early Olduvai sites. First, the evidence of site geology, tool cut marks, and other clues to the formation of the Olduvai sites are explored. On this basis, the large mammal communities in which early hominids lived are investigated, using methods which compare sites produced mainly by hominids with others made by carnivores. Questions about hominid hunting, scavenging, and the importance of eating meat are then scrutinized. The leading alternative positions on each issue are discussed, providing a basis for understanding some of the most contentious debates in paleo-anthropology today.The dominant interpretive model for the artifact and bone accumulations at Olduvai and other Plio-Pleistocene sites has been that they represent home bases, social foci similar to the campsites of hunter-gatherers. Based on paleo-ecological evidence and ecological models, the author critically analyzes the home base interpretation and proposes alternative views. A new view of the Olduvai sites - that they represent stone caches where hominids processed carcasses for food - is shown to have important implications for our understanding of hominid social behavior and evolution.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Early Hominid Activities at Olduvai by Richard Potts in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Bed I Olduvai: A Case Study in Meoanthropologieal Inference

1

Introduction

Evidence from the earliest archeological sites has played a dominant role in ideas about the evolution of human behavior. On the basis of present evidence, early hominids from the Plio-Pleistocene, 1.5 to 2.5 million years ago (Ma), were the first to make stone tools. Tools and the sites where they are found have drawn the attention of paleoanthropologists and the public alike, for they suggest a time and a place for the origins of several distinctively human traits. The manufacture of tools has long been considered a product of manipulative skill and mental facility that is special to humans. The earliest human artifacts made from stone signify an incipient technology and the ability to enter hard or tough plant foods or to open up an animal’s carcass. The implication, according to traditional views, is that these early hominids performed economic functions that once characterized all humans, the ability to hunt and to gather food. Moreover, continuity in the shape of the earliest known tools over long periods of time appears to embody the essence of cultural learning, the passing of information across generations, and a unique medium for maintaining a way of life.

Probably more than the discoveries from any other paleoanthropology site, the finds from Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, have helped to shape ideas about the origins of these human behaviors. The first discoveries at Olduvai, between 1931 and 1959 by Drs. Louis and Mary Leakey, showed what very early stone tools looked like and what species of animals were contemporary with the hominid toolmakers. From 1959 through the early 1960s, fossils provided the first glimpses of those hominids. Actually, more than one species was found: the large-toothed robust australopithecine (Australopithecus boisei); the more lightly built and larger brained Homo habilis; and Homo erectus, the still larger brained successor to H. habilis. Fossils of both robust Australopithecus and H. habilis were found in the oldest sedimentary layers of Olduvai. On the basis of consistent spatial associations between stone artifacts and the remains of H. habilis, a case has been made that this species was the earliest toolmaker at Olduvai (Leakey, 1971). Although the idea is partly based on an assumption that the first stone toolmaker had a relatively large brain, it is now generally believed, though by no means proved, that early Homo rather than Australopithecus was responsible for the earliest stone tools throughout East Africa.

Research at Olduvai was directed not only toward discovering the maker of stone tools. In fact, the technology and overall activity patterns of the hominids were the primary focus of intensive excavations led by Mary Leakey during the early 1960s. Leakey’s excavations concentrated on the two geologic units at the base of the Gorge, named Beds I and II. Certain layers of fine-grain sediment within Bed I, in particular, contained clusters of stone artifacts and the broken, fossilized bones of numerous animals. These sites—such as FLK “Zinj,” where the first Plio-Pleistocene fossil of Australopithecus in East Africa was found—occurred in a zone of sediments laid down on the border of an ancient lake that no longer exists. The expansions and contractions of this lake were portrayed as gradual, undisturbing to the artifacts and bones deposited along its margin. This kind of geologic setting suggested to Leakey that the sites in Bed I were areas where hominids had brought stone tools and had eaten the meat of animals represented by bones. The animal bones found with the artifacts thus became especially important to interpretations of the Olduvai sites. Because of the presumed importance of these bones to the diet of hominids, excavations of dense concentrations of fossils and stone tools were called “living sites” (Leakey, 1971). Other paleoanthropologists working in East Africa, especially J. Desmond Clark and Glynn Isaac, came to the same conclusion and referred to the Olduvai sites as traces of early hominid campsites (Clark, 1970; Isaac, 1969, 1971). The layers of Bed I were dated approximately 1.75 million years old (Ma). Thus, the sites were nearly four times older than the earliest archeological sites previously known. The finds from Olduvai had pushed back the evidence for early hominid activities to almost 2 million years ago.

About 12 years ago, it became clear that the initial view of the Olduvai sites as areas of hominid activity, specifically campsites, needed reevaluation. There were two main reasons for this. First, researchers began to pay a great deal of attention to the ways by which stone artifacts and animal bones become deposited and modified. Studies of carcasses in modern habitats and in ancient deposits showed that a number of geological and environmental processes can affect bones in ways that may mimic the accumulation and preservation of such remains at archeological sites. Thus, while it once seemed straightforward to assume that the Olduvai sites preserved the undisturbed traces of hominid activity, it ultimately became necessary to test this idea rigorously (Isaac, 1983a).

A second motivation for reassessing the Olduvai sites was the increasing emphasis on both the differences and similarities between early hominids and modern humans. The campsite, or home base, interpretation of the Olduvai sites emphasizes the similarities of hominids to modern hunting and gathering peoples. However, the hominids of Bed I at Olduvai lived about 1.5 million years before the earliest Homo sapiens and possibly 100,000 years before the oldest known Homo erectus. Thus, it appears far too limiting to reconstruct the adaptations of the hominids at Olduvai by considering only behaviors observable in humans today. To apply present-day human analogies in a sweeping manner to ancient hominids essentially eliminates any question about behavioral evolution. Such questions must consider the possible antecedents to modern human behavior. Numerous archeologists have considered early hominid life to have been quite similar to that of modern hunter-gatherers, whereas others (e.g., Gould, 1980) state that the conditions of life before modern Homo sapiens were “fundamentally different from what they are today.” In an evolutionary perspective this point becomes the object of study rather than the major assumption.

With these reasons in mind, a personal study of the excavated remains from Bed I Olduvai was carried out. In this volume I will discuss mainly six levels excavated and originally described by Leakey (1971). Since a thorough account of these levels is provided in the next chapter, a brief description will suffice here. In five of the levels stone artifacts and animal bones were preserved, while only faunal remains occurred in the sixth. The remains were found in both thin and thick layers of sediment (approximately 9-68 cm thick) and concentrated in areas about 10-20 m in diameter. Each of these levels and the debris they contained are referred to as sites, representing distinct events or periods of bone, artifact, and sediment accumulation. A wide range of species have been identified from the fossilized bones, especially large mammals that ranged in size from gazelle (over 12 kg) to elephant. Most of the faunal remains were broken before burial and fossilization occurred. Stone artifacts from the five tool-bearing sites are diverse in size, shape, and raw material. They include pieces modified by percussion flaking (core tools), small flakes known as debitage, pieces apparently modified solely by their use as implements (utilized material), and unmodified rocks obtained from outcrops in the ancient Olduvai region (manuports).

What do these fossil bones and stone artifacts buried at Olduvai indicate about early hominids? Do they provide clues about hominid activity and adaptations to ancient environments? If so, what were these activities and adaptations? How did they compare with the behaviors of ancestral hominoids and of later humans? These general questions about the Olduvai sites are of greatest interest to students of human evolution.

There are four major aspects of this study. First, it is crucial to test the idea that the artifact and bone concentrations of Bed I represent primary areas of hominid activity. Second, based on an assessment of how the Olduvai sites were formed, the paleoecology of ancient Olduvai will then be explored. Reconstruction of the ecological settings in which hominids lived provides a necessary background for considering the possible adaptations of early hominids at Olduvai and why they may have developed. In this regard, the large mammal communities that existed at Olduvai are an important context for understanding the possible ecological roles played by these hominids.

It will be shown that several geological, biological, and behavioral agents or processes were involved in the formation of the Olduvai sites. Yet for the five levels containing artifacts and fauna, hominids were an important, and probably the primary, collector of these materials. A third goal of this study, thus, will be to assess what kinds of hominid activities led to the accumulation of animal bones and stone artifacts. Particularly interesting questions concern whether hominids hunted or scavenged for meat and other useful animal tissues, and how the transport of stone material and of bones were related to one another. In other words, how did hominid activities result in the creation of sites in the first place?

Finally, the traditional interpretation of the Olduvai sites as campsites, or home bases, will be examined. The home base hypothesis, explained in the following section, ties together many crucial elements of human behavioral evolution and, thus, it is one of the most significant and elaborate statements about the lives of human ancestors.

There appears to be little room to doubt that the development of home bases was important to the course of human evolution. However, the view expressed here is that the earliest hominid sites at Olduvai were not home bases but were antecedent to them. Although there is evidence for variations in climate and in the specific makeup of animal communities during the deposition of Bed I, throughout this period hominids collected stone materials and left them at specified locations. Parts of animal carcasses, obtained most likely by a combination of scavenging and hunting, were brought over a period of time to these places where stone material and tools were accumulated. These “stone caches,” I suggest, were areas for processing food—at least parts of animal carcasses—and the attraction of carnivores to these sites prohibited their use by hominids as the primary areas of social activity, that is, as home bases in the modern hunter-gatherer sense. Although this idea is less specific about the nature of hominid activities than the home base hypothesis, the view that Plio-Pleistocene hominids transported resources to specific places for reasons other than social ones has important implications concerning the development of home bases and the pace of hominid behavioral evolution.

The Home Base Hypothesis

Spurred by the finds from Olduvai, and more recently from Koobi Fora, Kenya, archeologists have become intrigued more and more with the reasons behind the evolution of humans. If, in fact, archeological sites provide direct traces of hominid activities, it is possible that the study of excavated remains will help in identifying “the patterns of natural selection that transformed these protohumans into humans” (Isaac, 1978). In this endeavor, the home base interpretation of the oldest sites is the most influential idea derived from archeological evidence about the evolution of human behavior.

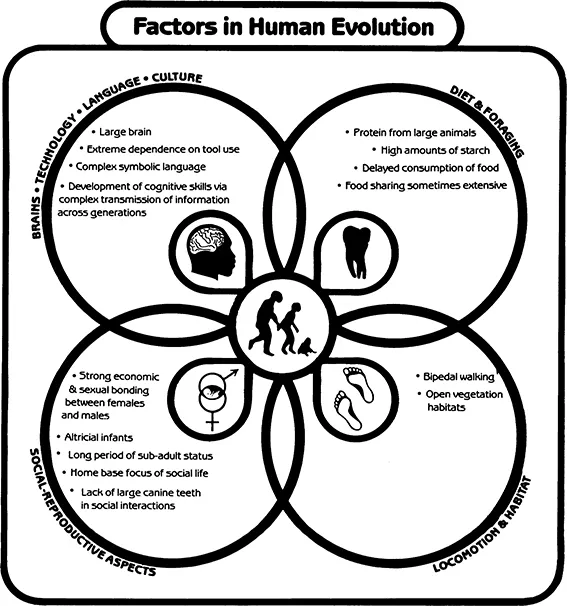

Glynn Isaac, in particular, pointed out that the origins of certain fundamental differences between humans and nonhuman primates may be explored by using the archeological record (Isaac, 1976, 1978, 1984). Figure 1.1 lists some of these distinguishing features. Because diet and food acquisition are vital aspects of an animal’s ecological niche and, therefore, evolutionary history, feeding activity is a salient point of comparison. The feeding behavior of modern humans tends to differ from that of nonhuman primates in two major ways. First, a relatively large percentage of the diet of many humans is composed of meat, especially from large mammals. Second, the eating of animal and plant foods is often delayed considerably after the food is obtained. It is often carried back to a home base, which serves as the spatial focus for food exchange, eating, and social activity.

FIGURE 1.1. The distinguishing features of human evolution may be considered as an interaction among four systems: locomotion and habitat; social-reproductive aspects; brains-technology-language-culture system; and diet and foraging.

Furthermore, in contrast with other primates, tools are required to process many foods and for other tasks carried out at the home base or while foraging. Another notable difference is that human offspring have a longer period of maturation. Both male and female parents—bonded socially by economics, emotion, and offspring—often play important roles in nurturing their children. Spoken language, that is, symbolically coded information used as a conventional form of communication, acts as a crucial medium of learning and social intercourse. Once again, the home base serves as a spatial focus where family members meet, offspring are nurtured, and the most intensive social contacts with other individuals of the group occur.

The home base interpretation of archeological sites 2 million years old implies that, by that time, these distinctive characteristics had already started to evolve in concert. Traditionally, archeologists have drawn similarities between the materials excavated from Paleolithic sites and the debris discarded by modern hunter-gatherers at their campsites (Isaac, 1983a). A somewhat idealized conception of the home base, derived in part from studies of tropical hunter-gatherers such as the !Kung San of Botswana (Lee, 1979; Lee and DeVore, 1976), has provided a model for interpreting the sites from Olduvai, Koobi Fora, and other Plio-Pleistocene archeological localities. According to this model, concentrations of artifacts and fossils from these sites are the relics of home bases—relatively safe locations where hominids ate, slept, and met members of their social group. The home bases of early ho...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Early Hominid Activities at Olduvai

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Part I. Bed I Olduvai: A Case Study in Paleoanthropologies Inference

- Part II. Formation of the Olduvai Sites

- Part III. Hominid Behavior and Paleoecology

- Bibliography

- Appendix A: Site DK

- Appendix B: Site FLKNN–3

- Appendix C: FLKNN–2

- Appendix D: Site FLK-22

- Appendix E: Site FLK North–6

- Index