1 Poles apart

Globalization and the development of news discourse across the twentieth century1

Allan Bell

Introduction

In this chapter, I take the media reporting of two expeditions to the South Pole as a case study in the development of news discourse across the twentieth century. The expeditions are those under Robert Falcon Scott (1910–13) and Peter Hillary (1998–9). They are parallel stories of exploration and hardship from the beginning and end of the twentieth century. The ways in which their news reached the world illustrate three related issues in the globalization of international communication:

- how technology changed the time and place dimensions of news delivery across the twentieth century (e.g. how fast the news is received, and through what medium)

- the consequent and concomitant shifts in news presentation (e.g. written versus live televized coverage)

- associated changes in how humans have understood time and place across the century – that is, the reorganization of time and place in late modernity (Giddens 1991; Bell 1999).

The remote location of Antarctica offers a specific advantage to these case studies: it stretches to the limits the technologies of communication and transport of the particular era, thus illustrating the boundaries of what is possible in news communication at the different periods.

The chapter’s theme is the way in which time and place are being reconfigured in contemporary society, and the role played in that process by changing communications technology, journalistic practice and news language. When is a defining characteristic of the nature of news, a major compulsion in news gathering procedures, and a determinant of the structure of news discourse (Bell 1995). News time is time in relation to place: what matters is the fastest news from the most distant – or most important – place (cf. Schudson 1987). I will track the changes in technology and the reorganization of time/place across the twentieth century, using as timepoints the New Zealand coverage of the outcomes of these polar expeditions.

Captain Scott: 1912–13

The British expedition led by Captain Robert Falcon Scott reached the South Pole on 18 January 1912. They hauled their own sledges 1,000 miles across the world’s severest environment from their base in McMurdo Sound on the edge of the Antarctic continent south of New Zealand. They found that the Norwegian, Roald Amundsen, had reached the Pole just a month before them.

On the return journey Scott and his party died well short of their base, the last of them on or after 29 March 1912. They were found eight months later by a search party sent out as soon as the passing of the Antarctic winter allowed travel. The relief party also found the detailed diary which Scott kept nearly to the last to tell the story of the calamitous journey.

News of their gaining the Pole and eventual fate did not reach the rest of the world until a year after it happened. In February 1913, the expedition’s relief ship Terra Nova put in to a small New Zealand coastal town and telegraphed the news in secret to London. Local reporters pursuing the story were rebuffed. The news was then circulated from London and published in the world’s newspapers on 12 February 1913, including in the New Zealand Herald, the country’s largest daily. This became the archetypal late-imperial story of heroism for Britain and the Empire, which stood on the verge of the Great War that would signal the end of their pre-eminence.

The front page of the Herald on 12 February 1913 (Figure 1.1) carries the same masthead in the same type as is used today, but the rest of the page is totally different – eight columns of small-type classified advertisements. The advertisements carry through the first six pages of the paper.

News begins on page 7 and in this issue is dominated by the Scott story. There are some two pages of coverage, nearly half the news hole, split into a score of short pieces with headlines such as:

HOW FIVE BRAVE EXPLORERS DIED HEROES LIE BURIED WHERE THEY DIED: A TENT THEIR ONLY SHROUD CAPTAIN SCOTT’S LAST MESSAGE TO THE PUBLIC

The stories cover the search for Scott’s party, reaction from other Antarctic explorers such as Amundsen, background on earlier expeditions and commentary on the fatalities. Two characteristics of the coverage appear here which are echoed again in the stories later in the century – first, nationalism as shown in the imperial geography of news. The information of Scott’s demise was sent to London from New Zealand, released in London, and only then transmitted back for publication in the New Zealand press. Second is the motif of the waiting wife – on 12 February Kathleen Scott was on a ship between San Francisco and New Zealand, coming to meet her husband on his return. She did not receive the news of his death till a week after it was public, when the ship came close enough to one of the Pacific islands to receive telegraph transmissions.

Figure 1.1 New Zealand Herald, 12 February 1913, front page

So we have here a ‘what-a-story’ in Tuchman’s terms (1978), dominating the news of the day – although not of course bumping the advertisements off the front page. In terms of the categories of news discourse which I use to analyse stories (see Bell 1991, 1998; cf. van Dijk 1988), all the central elements of time, place, actors, action and so forth are present.

The most obvious differences to a modern newspaper are visual – the absence of illustration, the small type even for headlines, the maintenance of column structure, and so on. What differs from later news discourse structure is that in 1913 the information was scattered among a myriad of short stories. Each sub-event has a separate story, which contemporary coverage in this kind of newspaper would now tend to incorporate into fewer, longer stories. All the information is there, and the categories of the discourse are the same, but the way they are realized and structured has shifted.

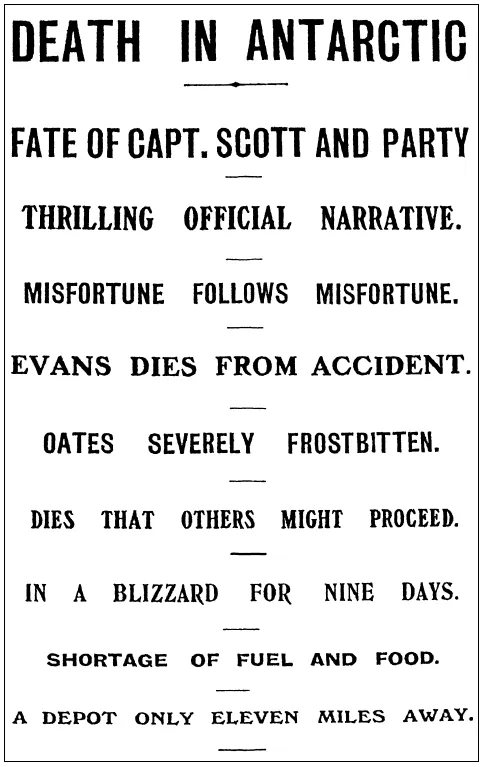

Turning from the general tenor of the paper and its coverage in 1913, we can focus on the specifics of the lead story, particularly its headlines (Figure 1.2). There are ten decks of headlines – not something one would see in a newspaper at the start of the twenty-first century. This is an extreme example because of the scale of the story, but five decks were not uncommon in the Herald at this period. The headlines are in fact telling the story. In some cases they refer to other, sidebar stories separate from the story above which they are placed. By contrast the modern headline usually derives entirely from the lead sentence of the story below it (Bell 1991), and certainly not from any information beyond the body copy of that story. That is, there is a qualitative shift in this aspect of news discourse structure across the century, from multiple decks of headlines outlining the story, to one to three headlines which are derivable from the lead sentence, with the story being told in the body copy.

The first striking thing in these headlines is an omission – they do not tell us that Scott reached the South Pole. No headline anywhere in the coverage in fact says that he reached his goal. The story is in the party’s perishing – and it has remained so. Let us assume that a contemporary newspaper would run a ten-deck headline like this. How would today’s headline writer edit these into contemporary style?

DEATH IN ANTARCTIC

The modern subeditor would have no problem with this: it could as easily be used today as a century ago.

Figure 1.2 New Zealand Herald, 12 February 1913, p. 8.

FATE OF CAPT. SCOTT AND PARTY

The honorific Capt. would be deleted, especially in this archaic abbreviated form, and party in this sense falls into disuse during the century. The Herald’s coverage of Peter Hillary’s 1999 expedition refers to the group and Hillary’s team-mates. It does use party but only in historical reference to Scott’s expedition. There is thus an intertextuality here by which the press uses the vocabulary of reporting from Scott’s own era when referring to Scott, rather than the labelling current a century later.

THRILLING OFFICIAL NARRATIVE

This is an impossible headline nowadays – lexically because thrilling and narrative (meaning ‘news story’) are both words of an earlier era, but more strikingly because of a shift in media and public consciousness. A century later thrilling and official can only be heard as mutually contradictory or ironical. Perhaps more tellingly, the concept of official narrative has shifted its significance. In 1913 it self-presents as the authoritative account of what really happened. The many stories about the Scott expedition published by the Herald on this day are sourced as ‘copyrighted official accounts’, the description clearly intended to reinforce their authority. In the twenty-first century such a labelling characterizes one voice – the official – among others. After a century of growing media and public scepticism towards official accounts, the undertone is that the ‘official line or story’ is to be regarded with suspicion. There has been a sea-change here in public and media attitudes towards authority and news sources.

MISFORTUNE FOLLOWS MISFORTUNE

Too ‘soft’ a headline for the press nowadays. It lacks hard facts, the repetition of misfortune wastes words, and the word is in any case too long. Linguistically it is the antithesis of modern headlining.

EVANS DIES FROM ACCIDENT

This would be made more specific, the multisyllabic word would again be rejected, and the temporal conjunction replace the resultative, because the temporal sequence is now taken to imply the causation – ‘Evans dies after fall’.

OATES SEVERELY FROSTBITTEN

Severely would be deleted as unnecessary detail.

DIES THAT OTHERS MIGHT PROCEED

This sentence would become rather ‘dies to save others’.The complementizer that plus subjunctive is archaic, giving way to the infinitive as a purpose clausal structure. Proceed again is nineteenth-century lexicon – ‘continue’ or ‘keep going’ would be preferred.

IN A BLIZZARD FOR NINE DAYS

Modern headlines do not start with a preposition, and this one would need a verb – ‘stranded’ perhaps. The rather static in would be replaced with more of an indication of agency – ‘by’. The article goes, and the preposition in the time adverbial is not required. The end result would be no shorter, but much more action-oriented and dramatic – ‘stranded nine days by blizzard’.

SHORTAGE OF FUEL AND FOOD

As a headline, this is too wordy to be contemporary. Fuel and food would be combined as ‘supplies’.

A DEPOT ONLY ELEVEN MILES AWAY

Again, the article would go (even though in this case there is some semantic loss – the zero article could be reconstructed as definite not indefinite: ‘the depot’). Perhaps a verb would be introduced, and the order might be flipped to keep the locational focus on Scott rather than the depot – ‘(stranded) just 11 miles from depot’.

Looking at the changes our mythical modern headline editor would have made, we can see both linguistic and social shifts:

(a) The ideological frame has changed – there is no longer just the ‘official narrative’, but the official becomes one account among others.

(b) The discourse structure has moved from multiple-decked headlines which almost tell the story, to single, short, telegraphic headlines which summarize the lead sentence.

(c) The lexicon has moved on. Some words strike as archaic less than 100 years later, for others length makes them out of place in a headline and they are replaced by shorter, punchier items.

(d) The syntax also has tightened. Function words drop out, there is a shift to emphasize action and agency through ‘by’ and the introduction of verbs. An entire clausal structure (‘that’ + subjunctive) has become obsolete.

Journalistically speaking, then, the news has become harder, the language tighter.

Peter Hillary: 1998–1999

Nearly a century later, on 26 January 1999, the three-person Iridium Ice Trek arrived at the South Pole.They took eighty-four days to pull their sleds nearly 1,500 km from Scott Base in McMurdo Sound. Their explicit aim was to recreate Scott’s man-hauled journey to the Pole, and to complete the trek back. Their leader was Peter Hillary, son of Sir Edmund Hillary whose expedition reached the Pole in 1958, and a significant mountaineer and adventurer in his own right.

The 1999 polar expedition was named for its sponsor, the ill-fated communications company Iridium.The team recorded a video diary of the journey as they went, and Peter Hillary commentated the daily progress of the expedition by satellite phone to the media.Their arrival at the Pole was videoed by Americans living at the polar station. The next day they flew back to Scott Base, having already decided to abandon the return journey on foot because of hardship and the lateness of the season.

The expedition arrived at the Pole at 5.17 p.m., and the world heard of their arrival within minutes.An hour after they got there, Peter Hillary was sitting on a sledge at the South Pole doing a live audio-interview on television and talking to his wife back home in New Zealand.

The main television evening news programmes in New Zealand go to air at 6 p.m. Early in this night’s programme, One Network News (on the channel which has most of the New Zealand audience) announced that Hillary was about to arrive at the Pole and carried an interview with their reporter at Scott Base. At 6.20 p.m., a third of the way into the hour-long programme, news of the arrival was confirmed and Judy Bailey, one of the two news-anchors, conducted a live telephone interview with Hillary:

Bailey And joining us now live by phone from the South Pole is Peter Hillary: Peter, congratulations to you all. Has it been worth it?

Hillary Oh look it’s – I must say having got here – ah – to the South Pole – everything seems worth it, Judy. I’m sitting on my sled at exactly ninety degrees south, it’s nearly thirty degrees below zero, but I wouldn’t – I wouldn’t want to be anywhere else. It’s just fantastic.

Bailey Peter, how are you going to celebrate this wonderful achievement down there?

Hillary Well I must say I think under different circumstances it could be very difficult but the Americans at the South Pole station have been most hospitable. About a hundred of them came out and cheered us as we arrived at the Pole and they’ve given us a wonderful meal. They’re making us feel very very much at home. Look it’s um – I ...