- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Focusing on the practical issues which need to be addressed by anyone involved in library design, here Ken Worpole offers his renowned expertise to architects, planners, library professionals, students, local government officers and members interested in creating and sustaining successful library buildings and services. Contemporary Library Architecture: A Planning and Design Guide features:

- a brief history of library architecture

- an account of some of the most distinctive new library designs of the 20th & 21st centuries

- an outline of the process for developing a successful brief and establishing a project management team

- a delineation of the commissioning process

- practical advice on how to deal with vital elements such as public accessibility, stock-holding, ICT, back office functions, children's services, co-location with other services such as learning centres and tourist & information services an sustainability

- in depth case studies from around the world, including public and academic libraries from the UK, Europe and the US

- full colour illustrations throughout, showing technical details and photographs.

This book is the ultimate guide for anyone approaching library design.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Contemporary Library Architecture by Ken Worpole in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1 The library in the city

DOI: 10.4324/9780203584033-1

CHAPTER 1 A city with a great library is a great city

DOI: 10.4324/9780203584033-2

The public library building is enjoying a new era of prestige across the world, with considerable architectural innovation during the past twenty years. Today, however, libraries are as much about creating places where people meet, read, discuss and explore ideas, as they are about the collection and administration of books in an ordered form. The idea of the modern public library as a ‘living room in the city’ is becoming a vital feature of modern urban culture, and architects are having to respond to this change of role. Towards the end of this chapter a schema is proposed which compares and contrasts the distinctive attributes of the traditional public library and the modern public library architectural paradigms. Such changes necessitate a major shift in the way these new building projects are developed and commissioned, and these highly political procurement and development processes are discussed.

Against expectations, the public library building is enjoying a new era of prestige across the world. So too are many other forms of library design and architecture, as higher education expands to meet a global demand for better educated populations capable of attending to their own intellectual self-development and professional expertise. No modern town or city is truly complete without a confident central library functioning as a meeting place and intellectual heart of civic life, echoing the sentiment of the inscription above the door of the grand reading room of the modern Nashville Library which opened in the summer of 2001: ‘A city with a great library is a great city.’

The core functions of these new libraries are not simply more of the same (and bigger and bolder) — they are different in very many ways from what has gone before. As architect and critic Brian Edwards has observed, ‘Libraries have seen more change in the past twenty years than at any time in the past hundred’ (Edwards, 2009: xiii). Edwards is one of an admirable group of contemporary library historians, architectural critics and practitioners, whose advocacy of the new library movement has been especially helpful in the writing of this book, along with Alistair Black, Kaye Bagshaw, Biddy Fisher, Shannon Mattern, Ayub Khan, Simon Pepper and Romero Santi. I also learned much from the study into new library buildings conducted at Sheffield University by Jared Bryson, Bob Usherwood and Richard Proctor. Many other researchers and writers are acknowledged at the end. Likewise the bibliography will, I hope, provide some idea of the scale and range of writing now available which regards the library building as central to the improved life chances and well-being of people in modern democratic societies.

In a special edition of the journal Architectural Review, devoted to ‘The Library and the City’, architectural critic Trevor Boddy (2006) expressed some scepticism about the so-called ‘Bilbao Effect’, which suggested that only iconic museums designed by world-famous architects could rescue failing cities from oblivion. He noted that, ‘It seems evident that the building that will come to emblematise the beginning of a new century of public architecture is not the latest Kunsthalle by Hadid, Holl or Herzog & de Meuron, but rather Rem Koolhaas’ Seattle Central Public Library.’ In this I concur, noting that in several of the most audacious designs for new world-status museums there is actually nowhere for people to sit or engage with each other. Who are these buildings really being designed for, and what is the nature of civic entitlement and democratic exchange embodied within them? Such questions are now being asked around the world as a generation of ‘iconic’ cultural buildings struggle to find revenue funding and audiences. For a devastating critique of the baleful influence and final implosion of the ‘Bilbao Effect’, few can better Deyan Sudjic’s acerbic essay on ‘The Uses of Culture’ in his book The Edifice Complex (2006), where Sudjic itemises the overblown rhetoric and spiralling costs of many of these grand self-referential museum projects, and their early demise or slow foundering.

The reason why libraries still have a clear civic edge over the proliferation of art galleries and museums of recent years — in the name of urban regeneration — is because they continue to provide a much richer range of public spaces than these other forms of cultural provision, public or private. It was Seattle Library’s ‘trailblazing take on public space’ that excited Boddy. He enthused that its ‘levels provide niches for scholars, corporate researchers, bibliomanes, teen-daters and even the homeless seeking refuge from the rain’ (Boddy, 2006: 45). This universal welcome and reach he stated, were ‘shared by most of the libraries gathered in these pages.’ Economic historian Edward Glaeser urges all those involved in future urban regeneration programmes to invest in people, and in projects such as public libraries which encourage learning, participation and the development of social capital, not grands projets providing consumer spectacle for those lucky enough to have time and money to spare (Glaeser, 2011).

Seattle Public Library

Now probably the most famous newly designed and completed public library in the world, Seattle’s Public Library opened on 23 May 2004. Designed by Rem Koolhaas and his Dutch firm, Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), along with LMN Architects in Seattle, its gigantic, deconstructed irregular mass now dominates one area of the city, and has clearly been designed to express the shock of the new, whilst simultaneously challenging every accepted cliché of what a public library should look like. It is said that Koolhaas refuses to accept architectural concepts such as ‘type’ and ‘generic style’, and believes that architecture should be based on a research-based approach to the design process that takes nothing as given but always starts with a tabula rasa. In his own words, the library is ‘a physical expression of the struggle to maintain the sanctity of public space and build an efficient, technological machine in a world that is in a constant state of flux’ (Mattern, 2007: 75).

The building’s strikingly unconventional shape — basically a series of five boxes (one below ground) stacked irregularly on top of each other, producing a set of cantilevered overhangs as well as deep insets — is said to make it more resistant to wind and earthquakes, reinforced by an exoskeleton of diamond-patterned steel mesh. Seattle journalist Regina Hackett aptly suggests that ‘the building has a split personality. All the brutal chic is on the outside, its diamondshaped steel and glass skin stretched over muscle … Inside, the library appears to change its character, starting with the assymetrical steel skin, which internally is painted a luscious and lulling baby blue.’ The deeply indented or extended edges on all four sides produced a range of lighting conditions inside which offer both shade and direct sunlight, all mediated by the steel mesh skin.

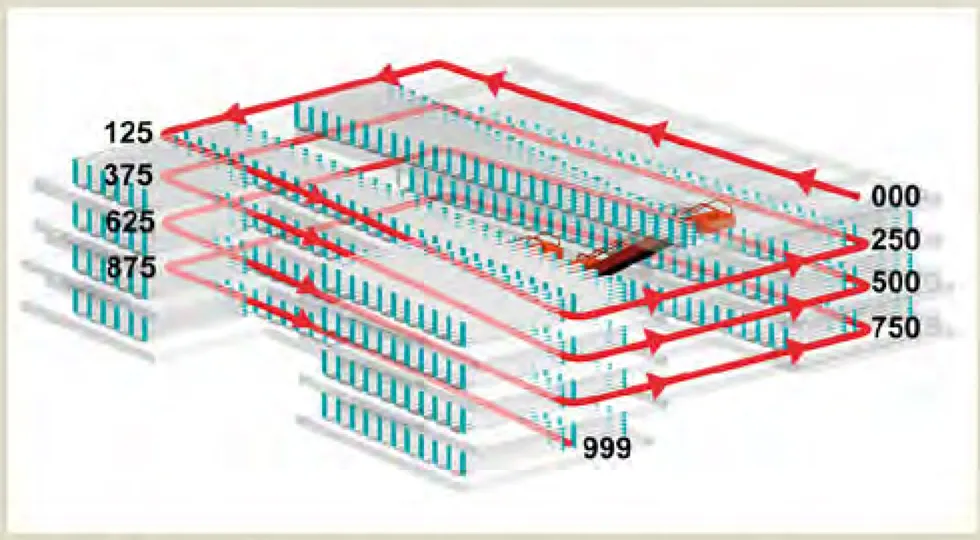

The internal spaces are located across eleven different levels, with the first five levels given over to children’s and teen library areas, auditoria, language centre, fiction, living room, café and meeting rooms, with the ‘mixing chamber’, described by one writer as a ‘trading floor for information’ taking up most of level 5. Above that the famous Books Spiral works its way up through levels 6, 7, 8 and 9 — where the main non-fiction stock is to be found in one continuous thread of shelving following an internal ramp which slopes continuously upwards at an angle of two degrees. At level 10 there is a large reading room with views out across the city, and, finally, level 11 is wholly allocated to administration. This schema or division of space is based on the programme being divided into five main compartments: Administration, Books, Meeting, Information and Parking. Those using the reading room to study, browsing for non-fiction, and thus likely to stay longer will need to rise further up the building. Those coming to attend language classes, to borrow a novel, or accompany children, or meet friends will find most of their needs met closer to the ground. Each floor is connected to the next by escalators as well as elevators.

To European eyes the building appears to become its own biosphere, almost entirely separate from the street or any kind of meaningful public landscape or street culture. It is its own world. But this is...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acronyms

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Part 1 The Library in the City

- Part 2 The Libraryness of Libraries

- Part 3 Planning and Design Processes

- Part 4 Selected Case Studies

- Part 5 Lessons for the Future

- Bibliography

- Further acknowledgements