- 340 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

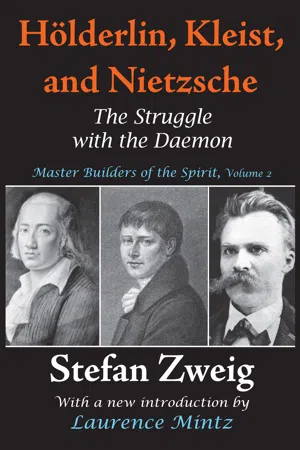

This is the second volume in a trilogy in which Stefan Zweig builds a composite picture of the European mind through intellectual portraits selected from among its most representative and influential figures. In 'Hoelderlin, Kleist, and Nietzsche', Zweig concentrates on three giants of German literature to portray the artist and thinker as a figure possessed by a powerful inner vision at odds with the materialism and scientific positivism of his time, in this case, the nineteenth century. Zweig's subjects here are respectively a lyric poet, a dramatist and writer of novellas, and a philosopher. Each led an unstable life ending in madness and/or suicide and not until the twentieth century did each make their full impact. Whereas the nineteenth-century novel is socially capacious in terms of subject and audience, the three figures treated here are prophets or forerunners of modernist ideas of alienation and exile. Hoelderlin and Kleist consciously opposed the worldly harmoniousness of Goethe's classicism in favor of a visionary inwardness and dramatisation of the subjective psyche. Nietzsche set himself as a destroyer and rebuilder of philosophy and critic of the degradation of the German spirit through nationalism and militarism. Zweig's choice of subjects reflects a division in his own soul. The image of Goethe recurs here as the ultimate upholder of Zweig's own ideals: scientist and artist, receptive to world culture, supremely rational and prudent. Yet Zweig was aware that Hoelderlin, Kleist, and Nietzsche were more daring explorers of the dangerous and destructive aspects of man that needed to be seen and comprehended in the clarifying light of poetry and philosophy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Holderlin, Kleist, and Nietzsche by Stefan Zweig in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

PhilosophySubtopic

Philosophy History & TheoryHÖLDERLIN

1770-1843

'Tis hard for mortals to recognize the pure of heart.

THE DEATH OF EMPEDOCLES

A Splendid Company of Youths

Childhood

Likeness as a Student in TÜbingen

The Poet's Mission

The Significance of Poesy

Phaethon, or Enthusiasm

Setting Forth Into the World

A Dangerous Encounter

Diotima

The Nightingale Sings in the Dark

"Hyperion"

"The Death of Empedocles"

HÖlderlin's Poetry

Fall Into the Infinite

Empurpled Obscurity

Scardanelli

A Splendid Company of Youths

"Night would for ever reign supreme, and

cold would be the earth,

The soul would be consumed by bitter

need, did not the gods,

In their goodness, send down such youths

from time to time

To refresh the wilting lives of mortal

men.

THE DEATH OF EMPEDOCLES

WHEN the nineteenth century was young, it was not fond of its young people. A new and ardent generation had arisen. Boldly and strenuously, in a Europe whose traditions had been shattered, it was marching from all quarters towards the dawn of unprecedented freedom. The bugles of the revolution had awakened it, and, rejoicing in the springtime, it was inspired with a vigorous faith. Before he was thirty, Camille Desmoulins, with a hardy gesture, had razed the Bastille to the ground ; a year or two older, Robespierre, the barrister from Arras, had made kings and emperors tremble before the blast of his decrees 3 Bonaparte, the little lieutenant, a Corsican by birth, had with his sword shaped the frontiers of Europe as he willed, and had seized the most splendid crown in the world—these deeds had made the impossible seem possible, had brought the splendours of the earth within the grasp of any man possessed of unshrinking courage. Youth's hour had struck. In the warmth of the vernal showers, the fresh green shoots of enthusiasm were sprouting everywhere from the soil.

Young folk were lifting their eyes towards the stars, were storming across the threshold of the coming century, their own by right divine. The eighteenth century had belonged to the old and the wise, to Voltaire and Rousseau, to Leibniz and Kant, to Haydn and Wieland, to the cautious and the patient, to the great and the learned ; now the times had ripened for youth and valour, for passion and impetuous-ness. Mighty was the wave in which they swept forward. Never since the days of the Renaissance had Europe known a more magnificent surge of the spirit.

But the new century did not like this intrepid offspring. It dreaded the exuberance, was mistrustful of the ecstasy, of its youthful enthusiasts. Relentlessly it mowed down the crop as soon as the tender green showed above ground. By hundreds of thousands the most intrepid were slaughtered in the Napoleonic wars; for fifteen years the noblest and the best were ground to powder in this murderous mill; France, Germany, Italy, the snowfields of Russia, and the deserts of Egypt, were littered with their bones. Nor was it enough to slay the body 3 the soul likewise was destroyed. Murderous wrath did not stop short after weeding out the warriors. The axe fell with equal truculence upon dreamers and singers who had scarcely emerged from boyhood when the century was opening. Never before in so short a time had there been offered up such a hecatomb of writers and artists as those who went to their deaths soon after Schiller (not suspecting the imminence of his own doom) had acclaimed their genius. Never had fate sickled such an abundance of illustrious and rathe-ripe figures. Never had the altar of the gods been sprinkled with so much divine blood.

They died in manifold ways, prematurely, in the hour of vigorous burgeoning. André Chénier, a young Apollo through whom classical Greece was reborn in France, was driven to the guillotine in one of the last tumbrils of the Terror. Had he been granted twenty-four hours more, had he survived the night between the Eighth and the Ninth Thermidor, he would have been saved from the scaffold and would have been restored to his work as a poet in whom the spirit of the singers of ancient Greece had found a new home. But destiny was inexorable, and would spare him no more than the others on whom her doom had been spoken. In England, after a long lapse into the commonplace, a lyrical genius had come to life, John Keats, delicately attuned to the beauties of the universe—to sing sweetly for a few short years and die at twenty-five. Shelley, his brother in the spirit, the ardent being to whom nature had revealed her loveliest mysteries, mourned over his grave; "Adonais" was the sublimest elegy ever conceived by one poet for another; yet in little more than a year Shelley was drowned wantonly in a storm and his body was washed ashore on the Tyrrhene strand. Byron, Shelley's friend and Goethe's favourite heir, hastened to the spot to erect a pyre beside the southern sea and burn the poet's corpse as Achilles burned that of his dead comrade-at-arms Patroclus; Shelley's mortal remains thus flamed into the Italian skies, but Byron himself was to die of fever two years later at Missolonghi. Within a decade the finest lyrical voices of France and England were stilled for ever. Nor was Germany spared a like destiny. Novalis, whose mystical piety had given him insight into the secrets of nature, had his light too soon extinguished, like that of a taper in a draughty cell; Kleist blew out his brains in despair; Raimund, too, committed suicide ; Georg Büchner perished of a nervous fever when only twenty-four; Wilhelm Hauff, a writer of fantasies, had no time for his genius to ripen, and went down to the tomb at the age of twenty-five; Schubert died of typhus before he was thirty-two. The members of this younger generation were laid low by the bludgeons and poisons of disease, by the frenzy of self-destruction, by the duellist's pistol or the assassin's dagger. Leopardi, the philosopher of despair, succumbed to a long and painful malady at thirty-nine 3 Bellini, the composer of Norma, was but thirty-four when illness carried him away ; Griboe-doff, the satirist, the brightest intelligence of awakening Russia, was the same age when stabbed in Teheran by a Persian. His body was brought to Tiflis, and it chanced that in the Caucasus, another great Russian genius, Pushkin, encountered the funeral procession. But Pushkin, too, died young, and by violence, being killed in a duel. Not one of these men lived to be forty, few of them to be thirty. The most luxuriant lyrical blossoming Europe had known was nipped in the bud; devastated was the splendid company of youths who in so many tongues were singing pseans to nature and glorifying the world. Lonely as Merlin in the enchanted forest, unacquainted with the new time, half forgotten and half legendary, Goethe, the ancient sage, lived on at Weimar ; there were no lips but his, withered with age, to voice an Orphic lay. At once progenitor and inheritor of this new generation into which he had persisted, he cherished and tended the fires of poesy in a brazen urn.

One only of the splendid company, the most typical, survived for many, many years in the world whence the gods had fled—Hölderlin, whose fate was the strangest of them all. His lips were still ruddy ; his ageing frame still moved to and fro across the German soil ; still did he gaze through the window at the beloved landscape of the Neckar ; he could still raise his eyes affectionately towards "Father Ether," the eternal sky. But his senses were no longer awake, being shrouded in an unending dream. The jealous gods, though they had not slain him, had blinded the man who had made their secrets known, had treated him as they had treated Tiresias the seer. His mind was enwrapped in a veil. With disordered senses, this man, "sold into slavery to the celestial powers," lived on for decades, dead to himself and to the world, while nothing but rhythms, waves of unmeaning sound, issued from his lips. The springtide with its blossoms came and went, the season he had been so fond of passed him by, for he noted neither its advent nor its going any more. Men flourished and died, and he paid no heed. Schiller and Goethe and Kant and Napoleon, the great figures of his prime, had preceded him into the grave ; steam-driven trains were thundering on iron roads across the Germany of his youthful visions. Huge towns were arising, new territories were being formed; but naught in these great changes stirred the numb intelligence. His hair was grey. The ghost of the man he had once been, he tottered hither and thither through the streets of Tübingen, made mock of by the children, despised by the students, none of whom could discern the marvellous mind that lay dormant behind the tragic mask. Long time, now, since anyone had given a thought to Hölderlin. Towards the middle of the nineteenth century, Bettina von Arnim became aware that the poet whom in her youth she had acclaimed as a god was lingering on in a carpenter's house, and she was as much startled as if one of the shades had come back to earth from Hades— so forgotten were Hölderlin's glories, so faded was his name. When at length he died, his passing attracted no more attention in the German world than the falling of an autumn leaf. Workmen bore his coffin to the burial place. Of the thousands upon thousands of manuscript pages he left, many were torn up and burned, while others remained to yellow and moulder in one library or another. Unread, unrecognized by a whole generation was the message of this last and purest of the splendid company.

Like a Greek statue buried in the earth, Hölderlin's image was hidden for decades in the rubbish-heap of oblivion. But just as, in the end, careful and loving hands have disinterred the works of the ancient sculptors, so has it happened with Hölderlin; and our generation has been amazed at the beauty of this marble figure. He lives once more as the last embodiment of German Hellenism, his inspiration, as erstwhile, finding expression in song. The springtides that he proclaimed seem immortalized in his personality; and, with the transfigured visage of the illuminate, he has emerged from darkness into the light of a new dawn.

Childhood

From their tranquil home the gods oft send,

For a brief sface, their darlings down to earth,

That, moved by the sight of such sublimity,

Remembering, the hearts of mortals may rejoice.

HöLDERLIN was born at Lauffen, a quaint old village on the Neckar, some few leagues downstream from Schiller's birthplace at Marbach. This Swabian countryside is the most appealing in Germany, it is the "Italy of the North." The Alps are not so near as to tower oppressively, and are yet within range ; the streams run in silver curves amid pleasant vineyards $ and among those who dwell there the harshness of the Alamannic stock is tempered by a cheerfulness which frequently finds vent in song. The land is fertile without undue luxuriance ; nature is bountiful without being spendthrift ; there is no sharp line of division between handicrafts and peasant agriculture. It is the true homeland of idyllic verse, this region where man's elementary needs are easily satisfied ; and even a poet whose mind is shadowed with gloom loses some of his bitterness when his thoughts fly back to the scenes of his childhood:

Angels of this our land! O you before whom even the strongest Must in his loneliness bow, bending a reverent knee,

Seeking support from his friends, and praying the help of his dear ones,

That they may gladly take part, share in the burden of joy— Bountiful angels, be thanked!

With what elegiac tenderness does the singer, his melancholy notwithstanding, write of Swabia, whose sky means more to him than the skies of the wider world ; how measured become his ecstasies when his mind returns to early memories. Compelled to leave his homeland, betrayed by the Hellas he had so fervently adored, frustrated in his hopes, he can still rejoice in the revival of youthful impressions, and embody them in verse:

Land where the smiling slopes have one and all of them vineyards!

Down on the lush green grass tumbles in autumn the fruit; Gladly the sunkissed mountains bathe their feet in the rivers,

Their heads wearing as crowns garlands of shrubs and of moss; And, like children carried lightly on fatherly shoulders,

Borne on the circling hills, strongholds and farmsteads uprise.

Throughout life Hölderlin yearned for this region where he had spent his childhood, and had enjoyed the happiest hours he was ever to know.

Kindly nature cherished him, kindly women saw to his upbringing, and it was his unhappy fate that his father should have died early, so that there was no one to discipline him by timely severity, no one to harden the muscles of feeling for the contest with his perennial enemy—life. Not in his case was there, as in Goethe's, a pedantic education capable of arousing a sense of responsibility. His only training was in piety, inculcated by his grandmother and his mother (a woman of gentle disposition); and at an early age the dreamer sought refuge from finite actualities in music—that infinity which is the first to lure a sensitive youth. But the idyll was brief. When he was barely fourteen the lad went as boarder to the monastery school of Denkendorf and then to the seminary of Maulbronn. At eighteen he became a student of theology in the university of Tübingen, remaining there till 1793. Thus for nearly a decade the liberty-loving boy was penned behind walls, under cloistral restraint, and dwelt in the soul-deadening proximity characteristic of a communal existence. The change was too glaring to be other than painful and even disastrous, the change from the freedom of hours spent in roaming through fields or beside the river, of days passed under the affectionate supervision of his mother, to the mechanized routine of a conventual discipline. For Hölderlin these seminary years were what the years as a cadet were for Kleist, years of repression which increased his sensitiveness, producing excessive tensions and leading to a flight from reality. A hidden sore remained, a kink which nothing could straighten. Writing ten years later, he says: "Let me explain to you that since early boyhood I have had a character-trait which is still the one I love best, what I may call a waxen impressionability of disposition; but it was this which was most grossly mishandled so long as I was in the monastery." During those years of repression, the noblest and most intimate element of his faith in life was being so maltreated that it was partly withered before the doors opened and he could return to the sunlight of the outer world. Thus early began, though only in a minor degree, the melancholy and the sense of being forlorn in an uncongenial world which were to cloud his spirit, and in the end to deprive him of all capacity for joy.

Such was the beginning, in the twilight of childhood and during the formative years, of that inward cleavage in Hölderlin, of that pitiless gulf between the world at large and the world of his own self. Here was a wound which never healed. To the end of his days he felt like one who has been driven forth into the wilderness; always he looked back with longing to the happiness of, his lost home, which often loomed like a mirage amid his poetic intuitions and memories, compounded of dreams and the strains of distant music. Perennially immature, he never ceased to feel that he had been snatched from this heaven of his youth to be thrust into a domain of uncongenial realities. That accounted for his hostility to his environment. Throughout life he remained unteachable. Though, from time to time, seeming joys alternated with gloom, happiness with disillusionment, none of these experiences could modify his attitude of alienation from reality. "From my earliest youth the world scared me, so that my mind was thrust back into itself," he once wrote to NeufFer. That was why he could never form binding ties or enter into effective relationships with his fellows, being what modern psychologists call an introvert, one of those who mistrustfully interpose barriers between themselves and stimuli from without, developing exclusively from within through the cultivation of the germinal characteristics implanted in them before birth. Half, at least, of his poems are inspired by the same motif, that of the insoluble opposition between trustful and carefree youth, on the one hand, and the inimical grown-up existence in which all illusions are lost, on the other j that of the contrast between a "practical" life in time and space and a life lived in the abstract world of thought. At twenty he wrote in mournful mood a poem to which he gave the title "Then and Now"; and in his hymn "To Nature" the same melody which from childhood ran ever through his mind rings forth anew:

...Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Introduction to the Transaction Edition

- Introduction

- Hölderlin

- Kleist

- Nietzsche