![]()

1 | Early Phonological Acquisition of German and Spanish: A Reinterpretation of the Continuity Issue Within the Principles and Parameters Model |

Conxita Lleó

Michael Prinz,

Christliebe El Mogharbel

University of Hamburg

Antonio Maldonado

Universidad Autónoma de Madrid

Introduction

Recent studies on phonological acquisition have largely discarded Jakobson’s hypothesis on the discontinuity of prespeech babbling and early word production (see Jakobson, 1941, p. 20) and have given support to the phonetic continuity of these two utterance forms. It is still controversial, however, to what extent early infant sound production is governed by universal principles or reflects language- specific influences. In recent years research on early phonological acquisition has focused on language-specific characteristics of babbling. Crosslinguistic studies have shown that young children have preferences for sounds and sound structures, which can be correlated with certain characteristics of the respective target languages. For instance, at the babbling stage Japanese children produce more back vowels than English, French, Chinese, or Arabic children (de Boysson-Bardies, Hallé, Sagart, & Durand, 1989), Swedish and English children produce more stops than French or Japanese children (de Boysson-Bardies & Vihman, 1991), and English children produce more closed syllables than French children (Levitt & Utman, 1992).

On the basis of these results, most researchers have argued that there is no evidence for a separation of babbling and first words and, thus, that the Jakobsonian view was incorrect. It is not only the case that features of the target language are already traceable in the babbling stage and that both sound productions temporally coexist, but it is further the case that babbling and first words share phonetic material, so that the sounds that constitute the first words are the sounds preferred during the babbling stage (de Boysson-Bardies & Vihman, 1991; Vihman, 1993; Vihman, Macken, Miller, Simmons, & Miller, 1985). Manysounds and sound structures produced at the babbling stage constitute a common core, contained in the productions of all babbling children and also contained in all languages of the world, like coronals, stops, nasals, and CV syllables (Locke, 1983). These are the sounds and sound structures purported to be less marked.

Concomitantly, if at the babbling stage children produce sounds that are not included in their target languages, but which constitute a unitary set produced by all children independently of their target languages, this might provide some substance to the discontinuity hypothesis. It is thus necessary to ask a fundamental question: Is the production of sounds not belonging to the child’s target language an indicator of chaos, that is, lack of phonological organization? In other words, does the presence of such sounds in babbling imply that the phonological component of the lexicon develops according to its own dynamics and runs independently from babbling, that it is formally and functionally separated from it?

A crosslinguistic study is presented here in order to examine the question of the universality versus language specificity of babbling. With this study, a contribution is made to the continuity issue from the point of view of the “Principles and Parameters” model. In this view, children have access to grammatical rules and primitive symbols of the same type as adults do. Continuity thus lies in the qualitative nature of the linguistic abilities, in the formal nature of grammatical rules and representations, and in the way of realizing these in comprehension and production (Pinker, 1984, p. 7f). Under this assumption, the child’s intermediate grammars will not fall outside the variation range allowed by the principles of Universal Grammar (UG; Carreira, 1991, p. 4). Accordingly, the child has access to general principles of UG, some of which leave several options open—the so- called parameters—which are then set along the values of the input language. For a more detailed description of the model and some of its applications to syntactic acquisition, see, for instance, Chomsky (1981), Flynn (1987), and Roeper and Williams (1987).

This model was mainly proposed for and has mostly been tested within the syntax. In the realm of phonology there have been some proposals that have been more or less worked out: on the syllable (Kaye, 1989), on autosegmentalization of features (Goldsmith, 1979), on underspecification (Clements, 1985), as well as other parameters related to suprasegmentals, such as stress (Dresher & Kaye, 1990; Halle & Vergnaud, 1987). The present chapter concentrates on parameters relating to phonological feature hierarchy, to spreading of phonological features, and to the structure of the syllable at the transition from babbling to the first words. Having the continuity issue as the background point of reference, two kinds of hypotheses should be tested: (a) Within a universal grammatical-theoretical continuity view, children are expected to acquire only those aspects of language allowed by the principles of UG (Carreira, 1991; Pinker, 1984), and (b) a language-specific interpretation of the continuity assumption implies that there must be signs of the target languages in the early grammars (de Boysson-Bardies & Vihman, 1991; Vihman et al., 1985).

According to this interpretation of continuity, early sound production will contain sounds and sound structures determined by the principles of UG and then be subject to parameterization, provided that the setting of a certain parameter is allowed by the corresponding stage of development of a particular child. Consequently, babbling and early words should manifest universal characteristics shared by the utterances produced by all children, independently of the target language and stemming from UG, and they should progressively contain language-specific characteristics determined by the target language. According to the hypotheses defended in this chapter, these two aspects should have a different weight in babbling and early words, babbling being more directly controlled by universal principles and words involving a higher degree of parameterization. However, notice that both aspects should be present in both utterance forms, and that the difference is a matter of degree rather than one that is qualitative. If these hypotheses are verified, continuity in its theoretical-grammatical-universal and in its language-specific interpretation will be confirmed.

This chapter makes an empirical as well as a theoretical contribution. On the one hand, research on the transition from babbling to speech is given a larger empirical basis, because crosslinguistic German and Spanish developmental data corresponding to such an early age have never been analyzed before. On the other hand, the chapter makes a contribution to the theoretical body on phonological acquisition by reflecting on the continuity issue, in the sense briefly discussed above.

Method

The analysis is based on a longitudinal investigation of five children acquiring German in Hamburg and four children acquiring Spanish in Madrid.1 The investigation began when the children were between 8 and 9 months of age. The German infants were audio recorded twice a month in their homes using a high-fidelity Sony TCD-D10 PRO cassette recorder and a portable Beyerdynamic microphone concealed in a vest that the children wore. The Spanish infants were both audio and video recorded once a month with a Panasonic video camera, and the same audio equipment used for the German children.

The infants were all recorded in unstructured play sessions with the mother and one investigator. In the German sessions, the situational context was noted by a second investigator. Both the German and the Spanish recordings were transcribed by the German research team. Each session was transcribed by at least two trained phoneticians by means of IPA (International Phonetic Association, 1989) symbols, using Revox B215 recorders. IPA symbols were complemented according to the suggestions made by Bush, Edwards, Luckau, Stoel, Macken, and Petersen (1973), and by further signs designed for the purpose of this project. Segments that could not be agreed on for transcription were discarded.

Six sessions for each child were chosen for analysis, corresponding to the following points:

- babbling only (age 0;9)

- babbling only (age 0; 10)

- at least 1 word type (age 0;11 to 1;1)

- at least 4 word types (age 1;0 to 1;5)

- at least 15 word types (age 1;3 to 1;6)

- at least 25 word types (age 1;4 to 1;8)

These points coincide in part with those set up by de Boysson-Bardies and Vihman (1991). Thus, our results are, to a high degree, comparable with their crosslinguistic investigation, which encompassed English, French, Japanese, and Swedish. The present study adds two more language groups not included in the database they examined.

The data were submitted to frequency counts of laryngeals, place and manner of supralaryngeal consonants and syllable structure (branching of rhymes). All calculations were done for words and babble separately.

Because the identification of words produced at such an early age may not be straightforward, it is appropriate to refer to the criteria applied. In general, the decision that a particular word had been produced was based on Menn (1978, pp. 21–26) and Vihman and McCune (1994). Menn’s minimal requirement consists of the recurrent association of a sound pattern and a meaning, although both may exhibit a certain degree of variation; she thus further requires that a “well-behaved word” be “phonetically consistent” and “semantically coherent” (p. 24). Vihman and McCune (1994) complemented Menn’s proposal by trying to formulate an operational method based on more precise requirements, such as the existence of a “determinative context,” as well as usage in multiple situations and identification by the mother. Phonetic criteria are also considered necessary, such as a certain degree of phonetic similarity to the target word. In our analyses, an utterance had to satisfy most of these criteria in order to qualify as a word. Imitations—utterances produced immediately after an adult model was provided—were not considered for analysis, except for the additional help they might have supplied to the identification of particular words. So-called “proto-words,” like onomatopoetic expressions and imitations of animal sounds, have been included in the analysis, although here the criteria just discussed, especially the phonetic ones, had to be applied in a loose way.

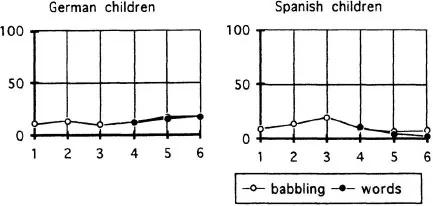

The results presented and discussed later (Figs. 1.1–1.5) show the average language group values for each of the six points listed earlier, thus giving information on the development over time. To test statistical significance, variance measures (two-tailed student-? tests) were conducted on three scores (Tables 1.1–1.2): for babbling, the first and second points (abbreviated B); for the word phase, the fifth point (W1) and the sixth point (W2). They are listed here for ease of reference:

Fig 1.5. Percentages of closed syllables out of all syllables produced at each point.

B | babbling only (points 1 and 2) |

W1 | words from point 5 (15 words) |

W2 | words from point 6 (25 words) |

Probability values were determined on the basis of the percentages for these three scores, calculated separately for German and Spanish. The value p ≤ .05 will be considered as significant, p ≤ .1 as marginally significant and p ≤ .01 as highly significant.

Results

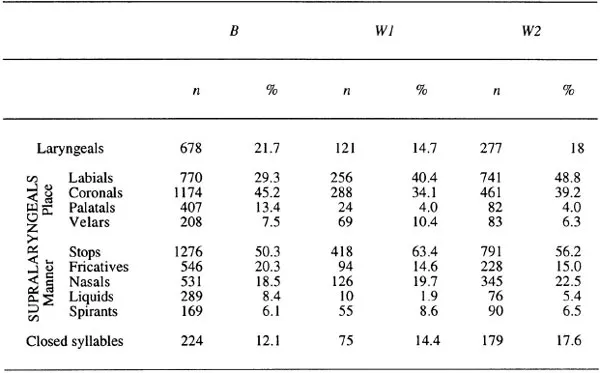

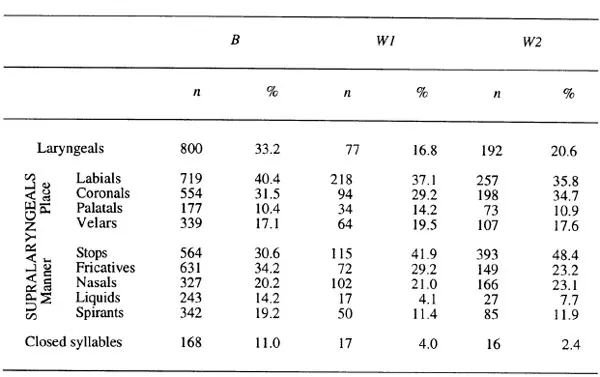

Tables 1.1 and 1.2 contain a summary of the results regarding the distribution of laryngeals, place and manner of supralaryngeal consonants, and closed syllables for the German and Spanish infants, respectively. The values for laryngeals and supralaryngeals are complementary: Both categories together sum up to the total of consonants produced by each group. The class of Fricatives refers to fricatives and approximants. The category Spirants represents an additional subclass under Manner, selected out of fricatives (and approximants), its values being already included within this category. The points illustrated in the tables—B, W1 and W2, correspond to those considered for statistical analyses.

Table 1.1 Summary of the German Data: Numbers and Percentages of Laryngeals, Place and Manner of Supralaryngeals, and Closed Syllables at the Three Statistically Relevant Points (Babbling, 15 Words, 25 Words)

Table 1.2 Summary of the Spanish Data: Numbers and Percentages of Laryngeals, Place and Manner of Supralaryngeals, and Closed Syllables for the Three Statistically Relevant Points (Babbling, 15 Words, 25 Words)

Laryngeals

Besides the information on laryngeals [h] and [ʔ] presented in terms of percentages in Tables 1.1 and 1.2, Fig. 1.1 illustrates their longitudinal development. Here, too, the percentages were calculated out of all consonants produced at e...