Part I

A Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow

I remember a show from the 1964-65 World’s Fair. The marionettes danced on the stage. “Oh—it’s—a—great—big—beautiful—tomorrow,” they sang, making stilted marionette motions by tilting their heads to mark every word: “a—great—big—beautiful—tomorrow.”

Millions saw that show, and I think of it whenever I read of a new scheme for the future. A family of life-sized marionettes starts out in a turn-of-the-century house and many scenes later ends up in the future. The stage revolves, and with each scene the appliances get newer as the marionettes gracefully age. The wood-burning stove becomes the gas range, electric range, microwave oven. And in the last scene—the great big beautiful tomorrow—there were the space-age shapes of appliances, the magic of the future, so close it made you want to reach up and touch the things on stage. The message was clear: Better things—through consumption—were on the way. Progress was sketched into infinity.

We would leapfrog into the future invention by invention, toaster by blender, appliance by appliance, until at last, all our devices in order, we would arrive at a utopia somewhere the other side of the checkout counter.

3. “The unformulated, yet gleaming metropolis” portrayed by Hugh Ferriss in 1925. “ ‘The lure of the city’ is the romantic way of phrasing it: imagination sketches the rural youth who is ever arising to his dreams of ‘the big city,’” wrote Ferriss.

Each invention has promised so much. One example, of the hundreds that could be offered, is glass. The mountains of glass we now see around us in cities were once the herald of a new age. At the end of World War I, one architect wrote: “It is not the crazy caprice of a poet that glass will bring a new culture. It is a fact.” German architects wrote fervently about the new material. Bruno Taut proposed entire cities of glass. “Hurray for the transparent, the clear!” he wrote in 1919. “Hurray for purity! Hurray for crystal! Hurray and again hurray for the fluid, the graceftil, the angular, the sparkling, the flashing, the light-hurray for everlasting architecture.”

In the end, glass gave us the box for corporate culture—the mundane, the workaday, the nine-to-five face of our downtowns. Similar stories can be told of many of our inventions. (One has only to think of how we were introduced to atomic energy. By 1980, power would be “free like the unmetered air,” predicted Dr. John Van Neumann of the Atomic Energy Commission.)

The city, too, has been treated as an invention. Over the last one hundred years a succession of architects, planners, and a stenographer-turned-visionary (Ebenezer Howard) have proposed reordering things, each promising that his was the magic geometry, which like the tumblers on a lock, would open the way to the good life. “Well planned towns will foster well planned lives.” That was the reformers’ credo.

The spirit of earnest invention and born-again faith in new materials runs through so many of the plans to change the city. The world would be made anew. And at last—at long last-mankind would stand tall and free. The world’s cities, wrote the great modern architect Le Corbusier, “could become … irresistible forces stimulating collective enthusiasm, collective action, and general joy and pride, and in consequence individual happiness everywhere…. The modern world would begin to emerge from behind its labor-blackened face and hands, and would beam around, powerful, happy, believing. …”

And what would the “modern world” behold, once it rinsed off its “labor-blackened face”? A world so fantastic it was not even possible until the last years of the nineteenth century; proud cities of towers. Rows of towers in green parks, if it were to be Le Corbusier’s world. Rows of towers with a rushing city at the base, if it were to be a metropolis like those envisioned by Francisco Mujica, Hugh Ferriss, and others.

IF there is one invention that embodies the city of the future, it is the skyscraper. It was looked upon as the answer to congestion downtown and out in the countryside as a way to bring people closer to nature. All this sounds backward today, but in its infancy the skyscraper was—what else?—but the herald of a new age.

One can catch the excitement that these towers brought forth in the 1908 edition of King’s Views of New York. “The cosmopolis of the future,” it says under a drawing of the world to come, “when the wonder of 1908—the Singer Building, 612 feet high with offices on the 41st floor—will be far outdone, and the 1,000-foot structure realized.” Progress was measurable: 612 feet. It was an era when city guides boasted of buildings by adding up the tons of concrete poured and the miles of wiring used. (“If all the wiring were unraveled it would stretch….”) King’s Views proudly notes the 150,000 cubic feet of stone used in the Singer Building and its 11 acres of office space all under one roof. (The Singer Building was demolished in 1967.)

Not everyone sounded the chamber of commerce sirens. Henry James, returning to New York City in 1907 after years in Europe, was saddened by the new skyline. Many argued for the abolition of the skyscraper, among them Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, and the editor of the Journal of the American Institute of Architects. The debate is captured in this poem:

Among the architects, there were objections sensible and misguided. Thomas Hastings, one of the architects of the New York Public Library, argued in the New York Tribune of December 30, 1894, that a steel skeleton would soon rust and inspection would be needed. His partner, John Merzen Carrere, suggested a tax on all buildings above eight stories. George Post, himself an early exponent of the form, believed that towers would stop being built when they started crowding each other out, blocking the sunlight and thus making the lower floors unrentable.

One critic, Major Henry Curran, asked the central question. In a 1927 speech, he said: “Is it good sense not to have a dollar for any other city need, to pour it all into more traffic facilities to take care of a coagulated bunch of skyscrapers? Is that sense? Is that city planning? … That is where we are headed.”

The skyscraper fever was on the land in the 1920s, and there were many who were convinced that it was the shape of things to come. Where others saw “a coagulated bunch” of towers, Francisco Mujica saw the “climax of constancy and order.” Mujica, an architect and Mexican archaeologist, wrote a spirited defense of the tall building and a hymn to its future in his 1929 book, History of the Skyscraper.

“How difficult it would be for a New Yorker who had been absent for 40 years to find any feature of the old city panorama which has disappeared under the most formidable construction force ever recorded,” Mujica wrote. “Buildings which at that time were considered dominating seem to be crushed by the Babylonic masses of the city.” Up to this point, it sounds as if he were warming up for a lamentation, but Mujica continues: “This represents the highest efforts of man, the greatest achievements of architecture in our century, and the climax of constancy and order, which by the coordinating efforts of poor pygmies has made it possible to build the most stupendous city on earth.”

Far from causing congestion, the skyscraper, like every good invention, was a time saver. In his defense of the skyscraper, Mujica quotes from Harvey Wiley Corbett, an influential architect who advocated separating pedestrians on a level over traffic, a feature that became a constant in the skyscraper utopias.

The skyscraper made business more efficient, Corbett argued: “The business area is condensed and time is saved. The skyscraper is one of the modern inventions—a steel speed machine….” In contrast, Corbett offers the example of London, a city at that time of a four-story average, with businesses so scattered about that it was difficult to make three appointments in a day, he said; but the skyscraper, keeping workers off the streets, was “an actual relief of street congestion.”

The ideal city of the future, for Corbett and others, would contain entire communities in one building. The base of the tower would be for business. At the tower’s first setback, there would be an upper sidewalk “with promenades and terraces in fresh air and sunshine,” residences, and stores. The center of the building would have theaters, gyms, and swimming pools.

“When a man left his office, he could take an elevator home,” wrote Corbett. “The most congested traffic would be reduced and people could get the full benefit of the light and air available at the top of our cities.”

While this may sound confining—like living on a cruise ship that has run aground at 52nd Street—to Corbett it passed that key test of a utopia: It was just what we needed. “The tall building, like other honest architectural forms, is the result of fundamental human needs.” (How had we lived so long, for millennia, so close to the ground?)

People living outside the city would also have their “needs” met. Industrial designer Norman Bel Geddes proposed replacing Main Street with a skyscraper. In his 1932 book, Horizons, he wrote:

4. King’s Views of New York (1908) presented this “dream” of the future: “The cosmopolis of the future. A weird thought of the frenzied heart of the world in later times, incessantly crowding the possibilities of aerial and interterrestrial construction, when the wonders of 1908—the Singer Building, 612 feet high—will be far outdone, and the 1,000-foot structure realized; now nearly a million people do business here each day; by 1930 it is estimated the number will be doubled, necessitating tiers of sidewalks, with elevated lines and new creations to create subway and surface cars, with bridges between the structural heights. Airships, too may connect us with all the world. What will posterity develop ?”

“The public at large thinks of skyscraper architecture as applying only to large cities. There are many arguments for its application to the small town. All the merchants in a town of five thousand persons will some day pool their interests. Instead of putting up numerous little three-story and four-story buildings of their own, they will build one tower-type building in the center of the town. This tower will not need to be very high, yet it will make life much easier for the whole community. Mrs. Jones will find it more convenient for her shopping, especially in rainy, hot or cold weather. In rainy weather she will be dry from the time she enters the building until she completes her errands. In hot weather, the building will be cooled by conditioned air, and in cold weather, heated. She will not be going from one draft temperature to another and slipping on icy pavements. The doctor, the movie and the butcher will all be under one roof, along with the commercial and governmental activities of the town, including the theatre and the mayor’s office.”

Lay this tower on its side and Bel Geddes has anticipated by thirty years the shopping mall. (In the 1960s, the idea of putting entire communities in one building became something of an architectural rage. “Megastructures” were drawn that dwarfed the island of Manhattan.)

When Mrs. Jones arrived home from shopping in the “our town” tower, she might return to another tower. In many schemes, the tower was seen as a preserver of open space: The skyscraper was not only a time-saving invention, it was a spacesaving invention. Le Corbusier had proposed such towers in the green in his Plan Voisin for Paris (1925) and his Ville Radieuse plan (1935). Frank Lloyd Wright and others had worked variations on this idea as a way to update the garden city.

Raymond Hood, one of the architects of New York City’s Rockefeller Center, proposed a tower for the countryside in Dobbs Ferry, New York. He offered a classic explanation of his 1932 plan: “Why not make a tower? It fits everybody. The average family of city dwellers dislikes the coal bill, the repair bill, taxes and the countless expenses of running a detached house. He does like open country, trees, lakes, light and air. In a tower he has it all. Why pull up all those beautiful trees [and] cut up the countryside to form new real estate developments…. The city man lives outside the city because he likes the country. Why not give him the country as it is? He can have his house in the tower … and the country at his very door, wild and unspoiled.” In short, we can have it all. We can be Henry David Thoreau on the twentieth floor.

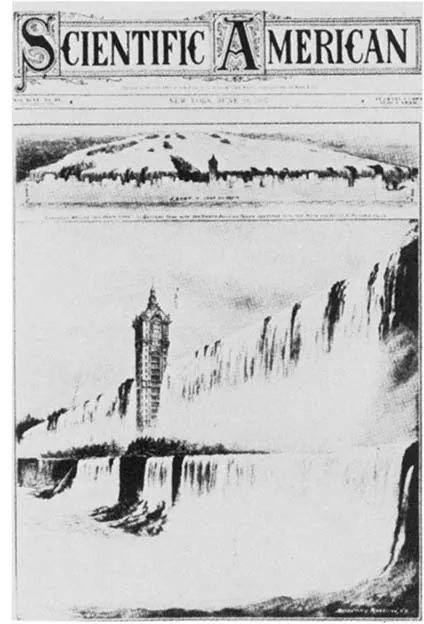

5 and 6. The construction of the Singer Tower, the world’s tallest building in 1908, was taken as a yardstick of progress. On the facing page, the Singer Tower is compared to the world’s tallest structures. On the cover of Scientific American, June 29, 1907, its height is compared to Victoria Falls and Niagara Falls.

Not only would the skyscraper bring the city to the country, it would do the reverse: Towers would rise, scruffy tenements would be leveled, and green space, like some inrushing sea, would fill the city. This was Le Corbusier’s vision in his many city plans. The tall towers would create enough income, he believed, so that the rest of the space could be left open. This has been one of the more influential ideas in the twentieth century. Almost every city in the world has some fragment of the “Radiant City.” It was a seductive vision: a city free of the squalor that reformers had been targeting since Dickens’s time; free of the crowded lanes of airless tenements where the “other half” lived.

Raymond Hood showed the influence of the idea in his 1927 plan for a “City of Towers”: “The city would throw off its outworn street plan. There would be no cumbersome overhead or underground streets, darkened alleys, fou...