![]()

Part I

BEFORE THE DEATH OF GOD

![]()

1 Plato

Plato (about 428–347 BCE), unmarried aristocrat and sometime cavalry officer, belonged in his youth to the circle of Socrates, a group of young Athenian men who admired and loved the philosopher (in spite of his snub nose, bald head and bulging eyes) and learnt from him how philosophy should be done. The most traumatic event in Plato’s life, which occurred when he was about 31, was the execution of Socrates, who was required to drink hemlock after conviction by the Athenian court on charges of ‘irreligion’ and corrupting the minds of young men. Other significant events in Plato’s life were his founding of the ‘Academy’, the first university (attended by, among others, Aristotle), and his three visits to Syracuse in Sicily. In his most famous work, the Republic, Plato argues that the ideal state can only come into being when the philosopher becomes king – or, presumably, when the king becomes a philosopher. The visit to Syracuse appears to have been an (unsuccessful) attempt to put theory into practice, to persuade the military dictator of Syracuse to govern his state according to the principles set out in the Republic. (A couple of millennia later, as we shall see, after Heidegger’s resignation from his post as an important Nazi official, a friend remarked ruefully: ‘Back from Syracuse?’)

Plato wrote some two dozen compositions known as ‘dialogues’ on account of their conversational form. In almost all of them, the main character is ‘Socrates’. Though modelled on the real person, it seems to be the case that, as Plato became older, ‘Socrates’ became ever increasingly his own literary construction, a mouthpiece through which he expressed his own ideas rather than reporting those of the hero of his youth.

Being versus becoming

As observed in the Introduction, the true world first enters philosophy in Plato’s mature dialogues. The foundation of his philosophy, expressed most famously in the Republic, is the division of reality into two worlds. On the one hand, there is the world of everyday visibility – the world that we see, smell, hear, feel and touch – which, because it is always changing, he called the world of ‘becoming’. On the other, there is the invisible, but nonetheless absolutely real, world of unchanging ‘being’.

The world of Being is the world of the ‘Forms’. The Forms are what account for the division of the visible world into kinds of things: this and that are both trees because they are ‘semblances’ – copies or imitations – of the very same thing, the Form of the Tree, ‘the tree itself’. This and that are both circles because they are copies of ‘the circle itself’, this and that person or action are courageous or wise because they are copies of ‘courage itself’ or ‘wisdom itself’. The things of this world are always imperfect copies of their originals in the world of Being. (However carefully you draw it, a physical circle will always have a kink in it somewhere, so it can only ever be an approximate circle.) In the Republic, Plato uses the image of the shadow to express the inferiority of everyday things to their originals. We physical creatures are like prisoners in a cave, chained so that we can only see the rock wall in front of us. Beyond the mouth of the cave behind us are real things which, because they are illuminated by the sun, cast shadows on the wall, shadows which most of us, because we cannot turn around, mistake for the real things themselves.

Though we cannot see the Forms physically, we can know them intellectually; we can see them in the ‘mind’s eye’. And in fact all human beings have a dim and confused knowledge of the Forms. This is the explanation of the defining human attribute, the ability to reason and communicate by means of language. The reason you can follow my instructions when I say ‘draw a circle’ is that what you have in mind when you hear the word ‘circle’ is the very same thing – circularity, ‘the circle itself’ – as I have in mind when I say it. The Forms are the meanings of words.

* * *

Plato, then, distinguishes between the true world of being and the ‘apparent’ world of becoming: apparent because, whereas, for Plato, things in the world of Forms are truly the things they are, things in the realm of nature are only approximately – i.e. not really – the things we take them to be. So far, this dichotomy looks to be a contribution to metaphysics and the philosophy of language. In fact, however, it is also the heart of a philosophy of life. To see why this is so, I want to examine one of Plato’s later dialogues, the Phaedrus.

* * *

The dialogue is set in the countryside, a short walk outside Athens. The place is an enchanted one, for it is where, according to legend, the wind god Boreas seized Orithyia from the river. The enchantment has its effect on Socrates. ‘Truly’, he says, noting, after a time, that his usually dry style of speech has become somewhat ‘dithyrambic’ (rapturous), ‘there seems to be a divine presence in this spot’ (P 238d).

The conversation is between Socrates and Phaedrus, a bright but impressionable youth. The topic is love. What makes it relevant to our concerns is that, in the course of discovering the nature of love, Socrates (Plato) deploys his true-versus-apparent-world metaphysics in such a way as to provide, in effect, an answer to the question of the meaning of life – an answer, moreover, which would dominate Western thought and feeling for the next two millennia.

The claim that love is madness

Phaedrus pulls from under his cloak a scroll that records a speech given by one Lysias, a speech by which he is mightily impressed.

Lysias’ speech is an attack on love. Though one senses that Lysias himself is not unlike the unattractive figure valorised in his speech, he does so principally in order to demonstrate his skill in rhetoric. As the ‘speaker for the affirmative’ in the school debating team might choose to defend the most absurd of positions in order to show off his skill as a debater, so Lysias chooses the scandalous path of attacking love in order, principally, to display his rhetorical virtuosity. (Scandalous and indeed blasphemous, because love, for the Greeks, was a god – Eros. To fall in love was to fall under the power of Eros.)

When deciding with whom to spend his time, the boy, Lysias argues, should consort not with the lover but with the non-lover, the man who frankly confesses to not being in love at all. Whereas the non-lover will offer a relationship of calmness and discretion, the lover will be jealous and possessive, isolating the boy from friends and other adult influences. When, however, the ‘disease or madness’ of love has passed, when the lover’s sick passion has transferred itself to a new object – as it inevitably will – then he will cast the boy off, abandoning him to a miserable and lonely existence.

(The context of this speech is, of course, homosexual. Though there was some uncertainty as to whether it should be allowed physical expression, love of boys was widespread among men of the Greek upper classes such as Plato and Lysias. Nothing of philosophical significance, however, hangs on this context. ‘She’s may be imagined in place of the ‘he’s at the appropriate places without, it seems to me, affecting the substance of the argument in any way at all.)

Heaven-sent madness

Lysias’ speech (which I have radically abbreviated) is long, rambling, boring and ugly. ‘How clever of Lysias to say the same thing twice over and with equal success each time’, remarks Socrates snidely. Nonetheless, faced with Phaedrus’ enthusiasm for its style and substance, Socrates decides that he must make a speech in defence of love.1 With Lysias as counsel for the prosecution, Socrates appoints himself, as it were, counsel for the defence.

Socrates starts by admitting that, as Lysias had claimed, love is indeed a kind of madness. But not all madness is bad. It is, indeed, precisely the opposite – ‘mankind’s greatest blessing’ – when it is ‘heaven sent’. One example of heaven-sent madness is poetry. Great poetry happens only when a ‘tender, virgin soul is seized … by the Muses who … stimulate it to rapt and passionate expression’. Poetry that is the product of merely ‘man-made skill’ is worthless. To produce great poetry, in other words, the poet must be ‘taken over’, ‘inspired’ by some supra-normal force. Poetry composed out of a mundane state of mind is mundane.

Another example of heaven-sent madness, suggests Socrates, is love. But to prove the point, he says, he needs first to provide a metaphysical account of the soul – of its nature, origin and ‘destiny’ (where it will, or at least ought, to end up). He provides this in the form of a narrative that abolishes the boundaries between poetry and prose, religion and philosophy.

The soul’s constitution

The soul, the source of all movement and action, is, says Socrates, immortal. The proof is as follows. We know that the soul is the uncaused cause of action, for when we decide to do something we freely so decide – nothing compels us to make one decision rather than another. But that means that the soul can neither come into nor go out of existence. It cannot come into existence, because then it would have to have, after all, a cause. And it cannot go out of existence because the only way something can cease to exist is through the removal of its originating and sustaining cause. As a ‘first principle of motion’, therefore, the soul is immortal. (This is actually a pretty dodgy argument, but I shall not labour the point.)

What, now, of the constitution of this immortal psyche? The soul, says Socrates, may be compared to

the union of powers in a team of winged steeds and their winged charioteer. Now all the gods steeds and all their charioteers are good, and of good stock, but with other beings it is not wholly so. With us men, [whereas one steed] … is noble and good and of good stock … the other has the opposite character and his stock is opposite. Hence the task of our charioteer is difficult and troublesome.

(P 246a–b)

Later on in the dialogue (drawing, perhaps, on his experience in the cavalry) Plato provides a fuller description of the two horses:

The good horse is upright and clean-limbed, carrying his neck high, with something of a hooked nose; in colour he is white with black eyes; a lover of glory but with temperance and modesty, one that consorts with genuine renown, and needs no whip, being driven by the word of command.

The other horse, by contrast,

is crooked of frame, a massive jumble of a creature, with thick short neck, snub nose, black skin, and gray eyes; hot-blooded and consorting with wantonness and vainglory: shaggy of ear, deaf, and hard to control with whip and goad.

(P 253d–e)

As Plato conceives it, the soul is a political entity. (In the Republic he argues that the structure of the state and the structure of the soul exactly mirror each other.) The charioteer represents ‘reason … the soul’s pilot’ (P 247b). Reason (or ‘intelligence’), he holds, is the legislative power in the soul. To it belongs the business of ‘command’, of ‘setting the course’ of action. The white horse represents the executive, the power of action; or rather, it represents the executive power of the soul insofar as it has an innate tendency to be in harmony with the commands of reason. The ‘massive jumble’ of the black horse represents the many-headed monster of physical desire which Plato refers to as ‘appetite’. It is, as it were, the rabble in the soul. In a harmonious, properly disciplined, soul, the energy of appetite is subordinated to the will of reason and thereby augments the motive power of the executive. (Freud, we shall see in Chapter 5, calls this appropriation of the energy of appetite ‘sublimation’.) Unfortunately, however, appetite often escapes the discipline of reason. As we shall see, disharmony in the soul, spiritual sickness, is always caused by rapacious ‘appetite’.

The fall and rise of the soul

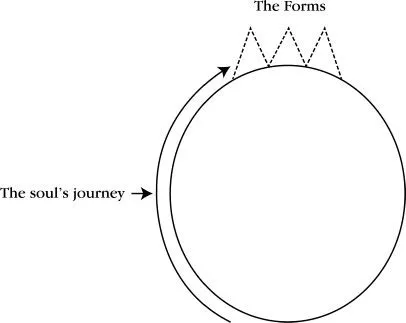

Originally, the soul belonged to the ‘train’ of one of the gods as it made its journey around the ‘rim of the heavens’. (Following a particular god makes one ‘most like’ (P 248a) that god. If, for example, one belongs to the train of Zeus one is likely to exhibit ‘constancy’, ‘wisdom’ and be a ‘leader of men’; if one belongs to that of Ares one is likely to exhibit a warlike disposition (P 252c–e); if one follows Apollo one is likely to be musical; if Hermes, gifted in speaking; if Hestia, home-making; and so on.) From its vantage point on the rim of the heavens the soul was able, periodically, to receive its ‘true nourishment’ (P 247d), namely, illumination by the Forms (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1

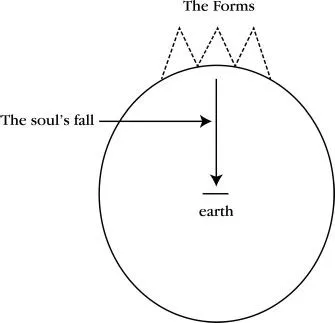

Figure 1.2

On account, however, of the struggle to control the black horse some souls had their wings broken. No longer able to fly, they fell to earth where they became incarnate, entered into material bodies (Figure 1.2).

Normally, there is no return to the rim of the heavens (and to the soul’s ‘true nourishment’) for 10,000 years. Rather, the soul is condemned to constant reincarnation in bodily form, its current position in the order of things being determined by the merit or otherwise of its previous life. If, however, the soul has three times lived the best life – the ‘philosophical life’ – then the period that must be endured before a return to the heavens is abbreviated to 3,000 years (P 248e–249a).

The philosophical life

What is the ‘philosophical life’? It is the life spent in the pursuit, not of power, fame, fortune or sensuous pleasure, but of knowledge, knowledge of the Forms. More exactly, it is the life that attempts to remember the Forms. Since all human souls once had direct experience of the Forms – as we have seen, they could not otherwise possess the distinctively human attribute of reason and understanding of language (P 249b) – knowing the Forms is really a matter of remembering them, just as, for instance, knowing the furnishings of one’s childhood bedroom is a matter of remembering them.

The other central characteristic of the philosophical life is that it is virtuous. It is, indeed, the only truly virtuous life. The Forms, remember, are the standards, ideals or perfect examples of which things in the everyday world are at best imperfect copies. So the Form of the wise, the courageous, the just and the good are the standards of wisdom, courage, justice and goodness. Now since, says Socrates, one obviously cannot consistently do what is good or wise unless one knows what is good or wise – know the standard that makes an action good or wise – it follows that only the life devoted to knowing the good and the wise has any chance of being good and wise. (To gain an intuitive grasp of the idea of the Forms of justice, wisdom, goodness, et cetera as standards or ideals, it may help to think of ‘role models’, and to observe that people who become role models are always, as role models, better, more perfect, than they are in their everyday lives. No man, as the French proverb observes, is a hero to his valet.)

Platonic love

What has all this to do with love? Where does love fit into the philosophical life?

Love, says Socrates, is essentially concerned with beauty. Now beauty, he argues, is unique among the Forms. In a difficult passage (P 250b–d), his argument appears to run as follows. As embodied beings, our typical and only easy access to things is through the physical senses. But beauty is the only Form that comes to presence in sense experience.2 To determine whether an action is genuinely just, wise or courageous one cannot just look; one has to think about it, usually in quite complex ways. With beauty, on the other hand, one does just look. Indeed, looking, one might argue, is the only way of determining whether or not something is beautiful. Hence beauty represents a kind of fissure through which something from the realm of Forms, a...