![]()

Chapter 1

The nature of our minds

We all sit in the driver’s seat of one of the most advanced pieces of equipment in the known universe, but it didn’t get delivered with an owner’s manual. Our vehicle has sophisticated functions developed and refined over thousands of years with a management system comprised of 100 billion neurons. Each one of these neurons can form connections with up to 10,000 others providing an unimaginably large number of possible wiring configurations. Much of the wiring at the back of the brain, close to the top of the spinal cord, controls the automatic functions, for example our heart and lungs. Many essential processes have become hard-wired to be automatic so that no conscious thinking is required, saving time and energy. Such hardwired automatic functions evolved at a very early stage of our evolution and are even referred to sometimes as the reptilian brain, as reptile brains have similar functions. Further automation of non-essential routine processes is helpful when we need to perform repetitive tasks such as riding a bike. We don’t want to relearn and rewire every time we sit on a bike and try to ride it, so once learned, the brain stores a relatively hard-wired circuit that can only be changed with active mental effort. Many of our daily activities follow this pattern. We don’t actively need to think about brushing our teeth, getting dressed or travelling to work with our full level of conscious awareness unless something new happens. Then energy consuming effort is required to think through how we should respond.

As we age, much of our behaviour is driven by patterns that have become habitual, probably appropriate at the time we acquired the pattern, but then used without consciously questioning whether modifications are required. We may be reluctant to change these habits, not wanting to invest in the mental effort required, telling ourselves that such habits are hard-wired in our brains and we can do nothing about it. But using habitual processes without review may take its toll. One of the most important discoveries in recent years, the concept of neuroplasticity, shows just how much of our brain can be rewired. Apart from the circuits for our basic functions such as breathing and some of our basic frameworks and processes, we don’t need to accept the ways in which we are currently configured for many aspects of our performance. Recent advances in the neurosciences and psychology have shown us that our brains are constantly reconfiguring themselves throughout life and with the right skills we can, to some extent, direct the way in which important parts are reconfigured. We can assert our self-agency, taking responsibility for consciously remodelling important functions within our brains. Coaches familiar with the functioning of the mind can facilitate this process by selective role play and, as we shall see later, encouraging personification of the various thinking modes available to us.

In our contemporary corporate business world, in addition to basic survival skills and specialist knowledge, well-developed social skills and emotional intelligence are needed to thrive. Many thousands of years ago humanity evolved into social groups of hunter-gatherers using more advanced parts of the brain for managing social interaction and coordinating group activities. Our social and emotional brain (limbic system) evolved to control reptilian instincts for easy quick wins according to the opportunities of the moment, enabling shared goals to be achieved by specialists working in teams. Hunting parties learned verbal and silent communication using gestures and facial expressions. Automated scanning systems were enhanced to observe and analyse threats and opportunities in the field of vision. Eye-gaze detection evolved to alert us to when we are being eyed-up as potential food or a target for sex. Visceral sensations were monitored more closely, contrib uting to an awareness of our embodied selves, our gut feel and what our sensory systems were picking up. Experiences were captured and indexed for future reference, particularly experiences suffused with emotional undercurrents so that we may quickly predict what a particular mix of sensory input, evoked feelings and emotions is likely to mean. An early warning defence mechanism developed, sharpening our get away (flight) or fight response, improving survival. But we also learned to override our basic instincts by enhancing our ‘toward’ response to socialise with each other so that we can engage in joint ventures with shared goals and shared longer-term rewards. Synergistic cooperation with others maximises our potential.

As social animals we do not only communicate verbally. The amount of information we receive or give away through facial expressions is surprisingly high. Paul Ekman, a psychologist in California, has led years of research into trying to understand the language of facial expression and has developed a Facial Action Coding System defining 44 unique action units: combinations of muscle contraction associated with different emotions such as sadness, fear, guilt, flirtation or disgust. His research also indicated that people learn to censor these expressions but usually there is a short delay, just time for the micro-emotion to leak out and be seen before the inter vention of higher cognitive functions. Authentic emotions and emotional masks can be distinguished and if we are sufficiently attuned to our environment we can detect the subtle signals concerning what the face reveals (Eckman and Rosenberg 2005). In processing these and other signals from around the age of four onwards, we are able to attribute mental states to other people in a process known as ‘Theory of Mind’ (Povinelli and Preuss 1995). We learn to sense what others may be thinking. Developing our ability to construct a theory about what is going on in another person’s mind is essential to our ability to read social situations and make appropriate judgements about how we should act. We start developing this process of tuning in to the mental state of another person by the time of our birth, interacting with our mother or other carer, learning from them how we may develop and regulate our own mental state. Thereafter, the mental states of others impact upon our own. We gain experience and shape our mental complexity through our interactions externally and internally (different hierarchical brain levels and the body), shaping and reshaping our minds throughout our lives (Karmiloff-Smith 2008; Diamond 2009).

Before we go any further it may be useful to define what we mean when we say ‘mind’. The working model of the mind suggested in this book is that the mind is an emergent process of self-regulation and self-organisation resulting from the interplay of energy and information between the hierarchical levels of complexity of the brain, the body and the environment. Recent scientific thinking suggests that the mind sculpts the brain through experience-dependent neuroplasticity, rather than the brain sculpting the mind.

Until recently the scientific understanding of how the brain works in real-time was far from clear. The technology did not exist to observe what happens as it happens. Neuroscience was based largely upon the observation of those with accidental or disease-damaged brains, or on simple neuronal-circuit models in the laboratory. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies, electroencephalogram (EEG) studies and positron emission tomography (PET) imaging has changed all that. Healthy volunteers performing tasks can be scanned to see which parts of their brains become active and in which circumstances. Such studies have revolutionised our understanding of how the brain functions and how these functions can be modified. Together with advances in the fields of psychology, interpersonal and social neuroscience and the contemplative traditions, we now have unparalleled opportunities to optimise our performance. We can use the functional specialisations of our brain in a more timely and intelligent way and use them in sequence to gain multiple perspectives on challenges we need to solve. We can modify much of the wiring in the cerebral cortex that no longer serves the purpose for which it was originally configured and now tends to hold us back, unconsciously getting in our way. We can enhance the connections between the functional ‘silos’ of our mind, applying our full range of skills to the challenges we take on. By understanding the new insights from cognitive neuroscience and basing mind-management on a systematic understanding of the dynamically interactive nature of the mind, we can engage in metacognition, thinking about thinking, so that rather than automatically defaulting to our habitual patterns, we can actively consider whether changes are required.

Awareness of the different functions provided in our various brain regions enables us to decide whether we would like to use more of one function and less of another; for example, use less of the alarm circuitry which raises stress levels and more of our sensory circuitry to tune into what our body is telling us. We can select different modes of reasoning (linear, logical quantitative reasoning or multimodal, complex qualitative reasoning) from different parts of our brain to enrich our decision-making process. Making the changes to the wiring in our brains needed to optimise performance does not require us to visit a neurosurgeon. We have built-in neurosurgical capability. We all rewire ourselves routinely, particularly during the first two decades of life, with major overhauls of our networks taking place during those difficult teenage years and again later during the mid-life crisis. It also seems possible to consciously direct the rewiring process in what has been called self-directed neuroplasticity remodelling (Schwartz and Begley 2002). By engaging in metacognition, thinking about our mental processes, and intentionally focussing our attention on these processes, feelings for example can be modulated (Ochsner et al. 2002).

Mindfulness techniques have been shown to change the brain areas that respond to everyday circumstances (Farb et al. 2007), resulting in improved decision making, reduced stress, better creativity, improved relationships, reduced conflict, better teamwork, improved leadership skills and better job satisfaction (Chaskalson 2011). The evidence supporting the effectiveness of mindfulness techniques in these areas is growing at an impressive rate. Brain scans have shown that we can change the wiring and firing patterns of our neural networks by refocussing attention and redirecting our effort leading to long-term structural changes in the brain. Clinical studies of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy have shown health benefits in areas such as depression and anxiety control (Segal et al. 2002; Crane 2008). The evidence base for certain health benefits has withstood scrutiny by the institute charged by the British Government to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of health-care treatments, The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Professor of Management Practice at Harvard Business School, Bill George believes mindfulness helps leaders to improve. In his experience, benefits included staying calm and focussed, more self-aware and more sensitive to the impact he was having on other people. He also reported positive effects on learning and memory, emotional regulation, cognitive perspective taking and stress reduction (George 2012). Companies such as Google, Astra-Zeneca, Apple, Transport for London (and the US Marines) have studied mindfulness benefits in groups of employees (or soldiers) and reported valuable results.

Cognitive techniques enable us to look at the mental models we have in our mind for representing our take on the world as we have perceived it. Perhaps these internal models need updating to reflect how our world has evolved to today, and perhaps our perceptions are overly biased by experiences from yesterday’s world. We do not need to learn technical details of the functioning of the brain in order to update our internal working models. A useful metaphor here may be to think of a television. There are the technical aspects of how a television is constructed with an array of sophisticated components to deliver high-definition pictures and quality sound. But few of us want to spend our time studying these components at a technical level. We want to switch on, select the channel broadcasting the program that best suits our needs at that moment and become engrossed in the show. Similarly we don’t need to learn the technical details of the functioning of the brain in order to run programs or change channels. Our mind decides what to watch and which features to engage in order to optimise our experience. Learning to use our minds to maximal advantage requires us to gain a sense of what the various functions of the brain do without going into technical details. And unlike a TV our minds not only receive transmissions, we can send them too!

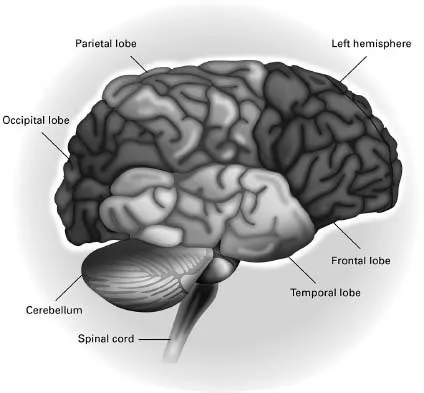

This Mind Manual begins by describing the functions of the most advanced region of the brain, the cerebral cortex where our higher level thinking is done. It is tempting to think of the cerebral cortex using the metaphor of a computer, particularly the part of a computer where all the computational processing occurs, the so-called central processing unit (CPU). First generation computers had only one CPU but as programs became more and more complex the single CPU format became rather slow and overloaded. Designers realised that to overcome this problem they could develop computers with more than one CPU and that the different CPUs could handle different types of tasks at the same time. We can now buy so-called quad or 4-core-processor computers that run much more sophisticated programs without getting stuck and integrate the results so that the user is only aware of one conscious output. Much processing goes on as unseen background activity. This is not a new trick; our cerebral cortex could be said to have evolved four cores (divided by a split down the middle, the longitudinal fissure, and divided between front and back, the central fissure) to enable background processing and also to facilitate some degree of specialisation within the different cores. These four cores may each use a different set of processes for evaluating sensory data. Increasingly, it seems that the right hemisphere tends to gather sensory data and synthesise it into patterns using a bottom-up approach whereas the left hemisphere tends to use frameworks created by the right hemisphere to interpret sensory data using a top-down approach. This imposes frameworks onto sensory data for rapidly drawing conclusions concerning its likely meaning.

The evidence for regional specialisation, although not universally accepted, has gained much ground recently (McGilchrist 2009; Ward 2010; Damasio 2012; Gazzaniga 2012). It is now understood that the reason for the power of the human brain is not down to its size but the way it is organised. If all the folds were smoothed out the cortex would more readily be appreciated as a highly laminated structure with columnar connectivity forming a complex mesh-like pattern. This structure is ideal for the formation of highly efficient local areas of functional specialisation and is the key to the brain’s scalability. This laminar and modular structure distributes consciousness across the brain and it is the function of the association cortex to link things together to make meaning. We can perform multiple complex parallel processing tasks in the background but we cannot follow these multiple lines of reasoning at the same time with our conscious attention. We know from our own experience that processing in our brain runs in the background when, for example, we try to recall a fact such as someone’s name, but can’t, until the answer pops up when we are focussed on something else.

It is important to keep in mind that the brain does not function like a classical digital computer. The human brain is an immensely complex structure and it has been estimated that ‘the complexity of our brain greatly increases as we interact with the world (by a factor of about one billion over the genome)’ (Kurzveil 2005: 147). The brain combines both digital and analogue (continuous processing) methods, predominantly using the analogue approach; it is relatively slow compared to digital computers but processes massively in parallel, rewires itself, and uses stochastic processing (random patterns within carefully controlled constraints): ‘The chaotic (random and unpredictable) aspects of neural function can be modelled using the mathematical techniques of complexity theory and chaos theory … Intelligent behaviour is an emergent property of the brain’s chaotic and complex activity’ (Kurzweil 2005: 151). ‘It uses its probabilistic fractal-type of organization to create processes that are chaotic – that is, not fully predictable’ (Kurzweil 2005: 449). This suggests that the probability of a particular action being generated is influenced by a huge number of factors in the environment, past and present.

Dynamic interactions influence our various functions in the same way that in a well-functioning organisation, people from different departments interact and influence each other’s thinking. So, rather than imagining the brain and the mind in terms of a conventional computer, to reflect quint-essentially human dynamic modulating effects, the metaphors used in this book draw upon the technique of personification (Rowan 2010) in which we try to embody clusters of associated functions as if they possess a personality. This idea is consistent with the view that ‘the self is constituted in some fashion out of a multitude of voices, each with its own quasi-independent perspective, and that these voices are in a dialogical relationship with each other’ (Baressi 2002: 238). Using this approach we are able to embody our sense of the nature of the functions contributing to a particular mindset and we also will see why it might be useful to hold multiple perspectives concurrently about the same issue. By personifying these sets of functions and embodying our internal dialogue in role play we may be able to clarify some of our internal confusions, helping us to move forward from an impasse.

Part 2 of the Mind Manual discusses how the limbic system integrates information from our cerebral cortices with our embodied emotions, bodily needs and the demands from the environment. This will help to understand our motivations and what impedes progress.

Part 3 reviews how events shape the nature of our minds over time. By understanding how events have been responded to in the past we can discover where our clients have got to on their developmental journey and co-create a way to unfold authentic potential. Various psychological theories provide probes enabling us to explore the way we have adapted to experiences. Some of these theories are briefly introduced to provide coaches with an overview of the tools most suitable for exploring a particular facet of personality. It is important to gain a sense of this developing complexity before proceeding to Part 4 which considers how our minds interact with each other and how we can improve collaboration to maximise collective performance.

Figure 1.1 | Layout of the lobes of the cerebral cortext sitting above the spinal cord, cerebellum and brain stem. |

Finally, Part 5 attempts to bring together the threads from the previous parts extrapolating into the future to reveal how it may unfold should we become more skilful in managing our minds.

As coaching and leadership development professionals...