- 258 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Laughter and Liberation

About this book

Laughter and Liberation is based on the idea that humor is an agent of psychological liberation. Since we are able to include every kind of wit and humor under the umbrella of this thesis, it amounts to an informal, comprehensive theory of the ludicrous. Briefly put, the theory proposes that the most fundamental function of humor is its power to release us from the inhibitions and restrictions under which we live our daily lives.The quest for laughter is as old as man himself Egyptian pharaohs and Roman emperors went to great lengths to amuse themselves, as did the monarchs of medieval Europe with court jesters. Our speech and literature abound with references to humor such as: "Laugh and the world laughs with you, cry and you cry alone," "He who laughs last laughs best," "All the world loves a clown," "Laugh if you are wise," and "A good laugh is sunshine in the house."In Laughter and Liberation, Harvey Mindess tells us how laughter and our sense of humor work. He gives us the background of several well-known humorists Steve Allen, Richard Armour, Sholom Aleichem and explains his theory of how and why they have become expert in making others laugh.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Laughter and Liberation by Harvey Mindess in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Section

One

From Laughter to Humor

If you tell a joke to a peasant, he will laugh three times: first, when you tell it; second, when you explain it; and third, when he understands it.

If you tell it to a landowner, he will laugh twice: first, when you tell it; and second, when you explain it; for he never understands it.

If you tell it to a Cossack, he will laugh only once: when you tell it; for he does not let you explain it, and that he cannot understand it goes without saying.

If you tell it to another Jew, however, he will not laugh at all. Before you’re half-way through he’ll stop you, shouting, “That’s an old one! I’ve heard it before, and besides—I can tell it better. ”

A superb example of Jewish wit, this traditional anecdote has merit on more than one level. Its structure is elegant, its social critique is neat, and, though this is hardly its point, it makes an important observation. People, it reminds us, differ in their sense of humor.

Stated so baldly, the assertion seems banal. No man in his right mind will debate it, nor will many of us give it a second thought. Yet its implications are highly significant. If our sense of humor is, as we know it is, an invaluable capacity, then our ability to exercise it is as crucial to our welfare as our ability to love. And if a fully developed sense of humor is, as I hope to show it is, our ultimate hope in this age of despair, then its cultivation is as important as any other task we can undertake.

Why then do people differ in this faculty? Is it simply, as our anecdote suggests, a matter of stupidity versus intelligence? And what is a fully developed sense of humor anyway? Is it the ability to get the point of jokes, or does it have anything to do with jokes at all?

Despite the astuteness of our illustration, there is more to the matter than it implies. Intelligence can, without question, contribute to humor, but it does not guarantee it. Many a brilliant man suffers from a sad deficiency of wit, while many a stupid one enjoys a lively capacity for laughter. And the appreciation of jokes, or even the ability to tell jokes effectively, is a criterion of humor only in a superficial sense. As the Hollywood sex symbol may, in real life, make a lousy lay, the professional comedian need not by any means command a genuine sense of humor.

Is a fully developed sense of humor, then, the ability to create spontaneous jests, to be personally witty and amusing —or does it extend beyond that too? We will soon come to see that it does. We will come to see that our sense of humor ranges beyond jokes, beyond wit, beyond laughter itself. While we will begin by examining laughter and funny stories, our study will lead us to a realm of experience that has no such tangible representation.

Humor, in the essence we are about to pursue, is a frame of mind, a manner of perceiving and experiencing life. It is a kind of outlook, a peculiar point of view, and one which has great therapeutic power. It can enable us to survive both failure and success, to transcend both reality and fantasy, to thrive on nothing more than the simplicity of being. Our sense of humor, in the deepest sense, is our ability to awaken and maintain this exceptional frame of mind.

Few of us, unfortunately, can lay claim to its fullness. The question is why. Why are we supposedly mature adults seldom able to actualize the possibilities of this faculty? To lay the groundwork for our answer, let us turn back to our beginnings, to the roots of laughter as they exist in infancy. If we understand what humor stems from, we will be in a position to comprehend the conditions that hinder the flowering of its most magnificent blossoms.

Within a few months after birth, all healthy infants laugh easily. Among the earliest laughter-provoking stimuli, two appear to be predominant. They are, first, mother (or any other familiar and comforting person) making an unusual face and, second, parents (or persons the child relies on for security) tossing the baby in the air and catching him in their arms.

What may we infer? Both the face-making and the tossing are disruptions of the infant’s cozy life; both are sudden, brief distortions of his usual experience. They upset .his stability, jolt him out of his little rut, and he delights in them as long as they are mild enough for him to tolerate. Now the intriguing analogue is this: disruption, distortion, the jolt— the experience of being jerked out of a rut—is an integral aspect of all types of humor.

In jokes, for example, we are led along one line of thought and then booted out of it. The twist or the punch line does the job; it is the joke’s equivalent to the baby’s flight or his perception of an unexpected set of facial features.

Three men lay dying on a hospital ward. Their doctor, making rounds, went up to the first and ashed him his last wish. The patient was a Catholic. “My last wish,” he murmured, “is to see a priest and make confession.” The doctor assured him he would arrange it, and moved on. The second patient was a Protestant. When asked his last wish, he replied, “My last wish is to see my family and say goodbye.” The doctor promised he would have them brought, and moved on again. The third patient was, of course, a Jew. “And what is your last wish?” the doctor asked. “My last wish,” came the feeble, hoarse reply, “is to see another doctor. ”

Here, as in the vast majority of funny stories, we are led to anticipate one sort of outcome and presented with another. The same holds true of spontaneous witticisms and deep-going humorous insight. Rather than operate in the expected, logical, or proper manner, the humorous mind skips about, shifts its view, and comes up with a surprising observation. “I can safely say I have no prejudices,” Mark Twain once declared. “Let a man be black or white, Christian, Jew, or Moslem—it’s all the same to me. AU I have to know is that he’s a human being. He couldn’t be worse.”

From Twain to Thurber to Feiffer to Perelman, from Laurel and Hardy to “Laugh-In,” the comic spirit is an embodiment of the spirit of disruption. It breaks us free from the ruts of our minds, inviting us to enjoy the exhilaration of escape.

The stimuli which rouse our laughter in infancy disrupt our perceptual system, the system through which we first organize our raw experience. When the baby sees his mother’s face distorted or feels himself flying through the air, he discovers the glee of being freed from the very source of his security. As we become acculturated, however, we acquire other organizing systems as well. Conventions, logic, language, morals: all are arrangements for structuring our raw experience, for bringing sense and order into our lives. Like the baby’s crib and mother, they are crucial to our security. They are also, however, deadening to the flow of sensation, impulse, thought, and feeling which arises out of our natural vitality.

When, in the interests of good citizenship, we restrain our desires to steal, cheat, lie, swear, gluttonize, fornicate, attack, and destroy; when, in the interests of sanity, we banish strange fantasies and irrational ideas from our minds; when, in the interests of adjustment, we abide by the habits and fashions of our society, we achieve a mixed blessing. On the one hand, we amass security and peace of mind; on the other, we sacrifice spontaneity and genuineness.

Here, then, is the essential irony of our human condition: the very acquisitions that provide our stability split us off from our authentic selves. And that—precisely—is where humor comes in. In the most fundamental sense, it offers us release from our stabilizing systems, escape from our self-imposed prisons. Every instance of laughter is an instance of liberation from our controls.

A lively sense of humor requires first a readiness to slip loose from organized modes of being. To enjoy it, we must be able to delight in disinhibition, to revel in utter foolishness. We must be willing to be impulsive, irreverent, impertinent. We must be capable of being unashamedly childish.

All humor is built on this foundation, but once we have reached maturity the foundation alone is not enough. Once we have been robbed of innocence, we are compelled to develop another dimension as well. We are compelled to understand: to understand human nature and human destiny, not in a theoretical or scientific fashion, but in a shrewd, sagacious way. Once we have known betrayal, corruption, defeat, no reversion to childish bliss is viable. Laughter grows out of a pristine state of fluidity, but to burgeon into full-flowered humor it must be fed with an awareness of the eternal human comedy.

A wit declares, “I used to be an atheist, but I gave it up. No holidays.” We may appreciate the jest at various levels, it is funny as a frivolous remark and as a put-down of the seriousness with which people take their religious affiliations. Beyond that, however, it contains a nugget of truth: the truth that our lofty religious and philosophical convictions really serve very mundane needs. The man who enjoys it at that level can be said to possess a more fully developed sense of humor than the man who does not.

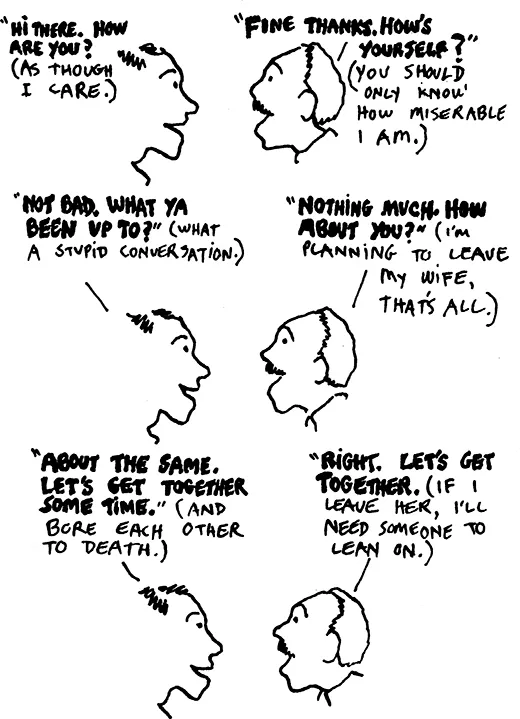

But jokes and quips, as we have already noted, fail to plumb the depths of humor. The material on which it flourishes is far more natural. Listen, sometime, to an ordinary conversation between two old friends:

“Hi there. How are you?”

“Fine thanks. How’s yourself?”

“Not bad. Whatya been up to?”

“Nothing much. How about you?”

“About the same. Let’s get together sometime.”

“Right. Let’s get together.”

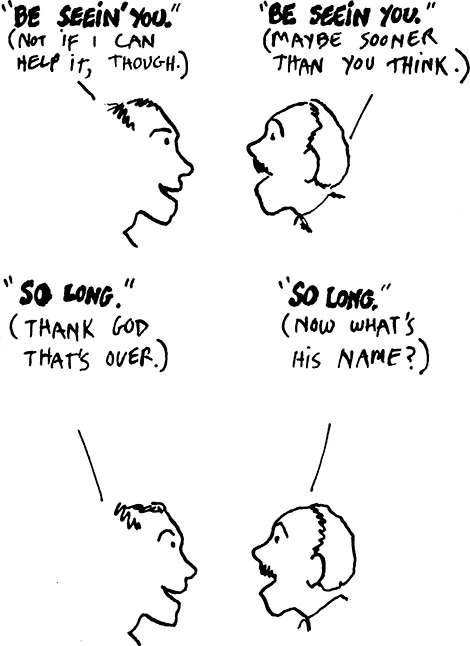

“I’ll be se ein’ you ”

“Be seein’you. ”

“So long.”

“So long.”

“Fine thanks. How’s yourself?”

“Not bad. Whatya been up to?”

“Nothing much. How about you?”

“About the same. Let’s get together sometime.”

“Right. Let’s get together.”

“I’ll be se ein’ you ”

“Be seein’you. ”

“So long.”

“So long.”

The insipid dialogue is worldwide; we are all participants in its counterparts every day of our lives; and since what we claim we crave is real relationship—a sense of communication, of knowing and touching and caring for each other—the situation is not devoid of irony. Could we tune in to the speakers’ thoughts, moreover, the irony would be compounded. It is probably no exaggeration to imagine they might run like this:

A rash of ironies, in fact, severely freckles the face of our existence. From the circumstance that those we love we often hate while those we hate we often envy, to the certainty that whatever we strive for is anticlimactic when we obtain it, a plethora of incongruities embroiders our lives. Nothing is exactly as it seems or nearly as we claim: that is the earth out of which sophisticated humor grows.

In order to command an adult sense of humor, then, we must keep ourselves aware of the paradoxes that characterize human behavior. We must know, not just in our heads but in our bones, that persons who preach altruism are motivated by egotism, that assertiveness is the mask of fearfulness, that humility is a kind of pride, that love is a euphemism for lust, that truth is the pawn of fashion, that we cherish our misery, and that we are all more irrational than we acknowledge.

We must know these things not as abstract principles but as practical rules of thumb. While our reason and idealism may be confounded at what goes on in the world, our deeper comprehension must expect it and enjoy it. If we are loyal, devoted spouses, we must understand that naturally we crave promiscuous liaisons. If we take a mistress or a lover to make up for what our marriage lacks, we must not be surprised to find that, instead of one problem, we now have two. If we are dreamers who laud the self-indulgent life, we must suspect that we really wish we could buckle down to hard work. Should we begin to work, however, we must anticipate that we will soon miss the lazy life we left behind.

A cartoon strip by Jules Feiffer expresses this outlook succinctly. It shows a housewife musing, “By the time George told me he was leaving on a business trip for a month I had lost all feeling for him. . . . Each dinner when he’d come home I’d try to rekindle the flame, but all I could think of as he gobbled up my chicken was: ‘All I am is a servant to you, George. . . .’ So when he announced he had to go away I was delighted. While George was away I could find myself again! I could make plans! . . . The first week George was away I went out seven times. The telephone never stopped ringing. I had a marvelous time! . . . The second week George was away I got tired of the same old faces, same old lines. I remembered what drove me to marry George in the first place. . . . The third week George was away I felt closer to him than I had in years. I stayed home, read Jane Austen and slept on George’s side of the bed. . . . The fourth week George was away, I fell madly in love with him. I hated myself for my withdrawal, for my failure of him. . . . The fifth week George came home. The minute he walked in and said, ‘I’m back, darling!’ I withdrew. ... I can hardly wait for his next business trip so I can love George again.”

In its early stages, our sense of humor frees us from the chains of our perceptual, conventional, logical, linguistic, and moral systems. The unexpected act, the startling remark, the nonsense quip, the pun, and the dirty joke are all, in the beginning, parties to our conspiracy of escape. In its more sophisticated stages, it releases us from our naive belief that man is a reasonable, trustworthy creature. Disillusioning wit joins the company of our abettors. To attain its ultimate, however, it must liberate us from identification with our own egos, for in this feat resides its quintessential power.

Tom Lehrer, the gifted comic singer, spoofs himself with versatility. On the jacket of an album entitled An Evening (wasted) with Tom Lehrer, we may read: “This recording was made in Tom Lehrer’s living room one evening when a few friends had dropped in and conversation was becoming strained. In a desperate attempt to save the evening . . . Mr. Lehrer rushed to the piano and performed the program heard here, making up the songs as he went along. Thanks to a quick-thinking engineer, who had happened by with his pockets full of recording tape, the whole fiasco has been preserved for posterity. ... In the hope of making the record slightly less wearisome, a certain number of coughs, hisses, snores, impacts, etc., have been edited out. ... If, despite these deletions, the record is still too tedious for you, you may wish to follow the procedure adopted by many owners of Mr. Lehrer’s LPs and play it at 78 rpm, so that it is over with that much sooner.”

Lehrer, of course, is posturing for an audience, so his self-mockery may be no more than a ploy to gain applause. In like manner, all of us make fun of ourselves at times to impress others with our apparent modesty or to ward off satirical attacks from outside. When, however, in a reflective moment, we really see how silly our ambitions and regrets, achievements and failures are, we inhale the rarefied atmosphe...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction to the Transaction Edition

- Introduction

- Section One

- Section Two

- Section Three